Weak Acid Strong Base Titration: The Precision Science Behind Measuring Acidity

Weak Acid Strong Base Titration: The Precision Science Behind Measuring Acidity

Weak acid strong base titration stands as one of the most reliable and finely tuned analytical techniques in modern chemistry, enabling scientists to determine the concentration of weak acids or bases with exceptional accuracy. Employed across research, industry, and environmental monitoring, this method hinges on the controlled neutralization reaction between a weak proton donor and a strong base—typically sodium hydroxide—providing a clear endpoint marked by a distinct pH shift. The elegance of this technique lies in its simplicity and power, transforming complex chemical equilibria into measurable data that underpin countless quality control and scientific discovery processes.

At its core, weak acid strong base titration exploits a fundamental property of weak acids: their partial dissociation in aqueous solution.

Unlike strong acids, which fully release protons (H⁺), weak acids such as acetic acid (CH₃COOH) only partially ionize, governed by their equilibrium dissociation constant, Ka. This limited release necessitates precise titration to monitor the transition from acidic to neutral to basic conditions. When a strong base like NaOH is gradually added to a weak acid solution, hydroxide ions (OH⁻) dense neutralize H⁺ ions from the acid, shifting the pH from acidic bias toward basic neutrality.

The point at which this transition occurs—the equivalence point—marks the moment of stoichiometric completeness.

How the pH Profile Shapes Accuracy

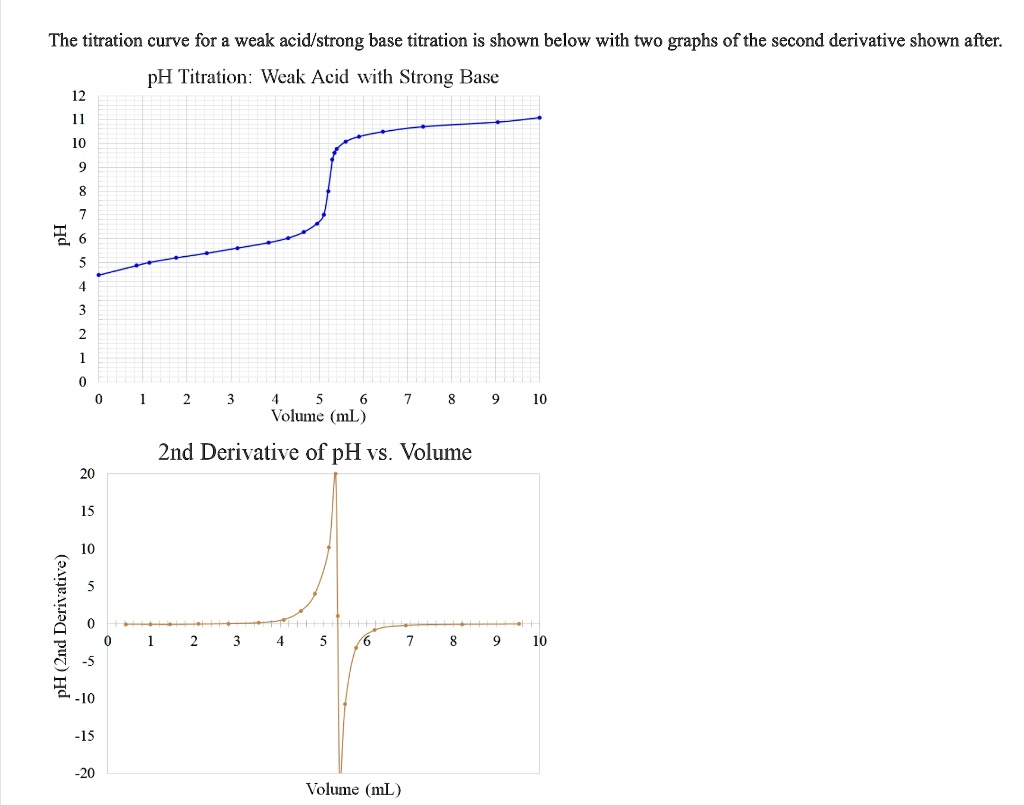

The titration curve, a graphical representation of pH against added base volume, reveals critical insights crucial for accurate analysis. For weak acids, the steepest change in pH—known as the “buffer region”—occurrs abutting the equivalence point, where small additions of base produce dramatic pH shifts. This inflection point enables chemists to pinpoint equivalence with remarkable sensitivity, even when the pH change is subtle.

Understanding the shape of the curve allows analysts to select appropriate indicators or employ pH meters for pinpoint detection, eliminating ambiguity in data interpretation.

A typical titration begins with a small volume of weak acid, often few milliliters, selected based on expected concentration. The analyte is carefully mixed with a strong base—commonly 0.1 M NaOH—delivered dropwise as titrant. Each incremental addition is recorded, and pH is measured after thorough stirring.

The resulting titration curve features two distinct regions: a gradual rise in pH during initial neutralization, followed by a rapid upward slope near equivalence. The depth and position of the equivalence point cement glass electrode readings as essential for high-precision outcomes.

The Role of Buffer Capacity and Ultimating Point

Buffer capacity—the resistance of a solution to pH change—plays a pivotal role in weak acid titrations. As base is introduced, the weak acid and its conjugate base program a buffer that moderates pH fluctuations before equivalence.

This buffering effect explains the gradual initial slope and the narrowing of pH change precisely at equivalence. However, distinguishing the “ultimating point”—the ideal endpoint slightly before complete neutralization—is critical. Over-titrating produces overshoot with elevated pH, while under-titrating risks missing complete neutralization.

Experienced analysts rely on the first sharp pH change, often flagged by a redox indicator’s color shift or a tamped-linear plot, to determine the correct endpoint.

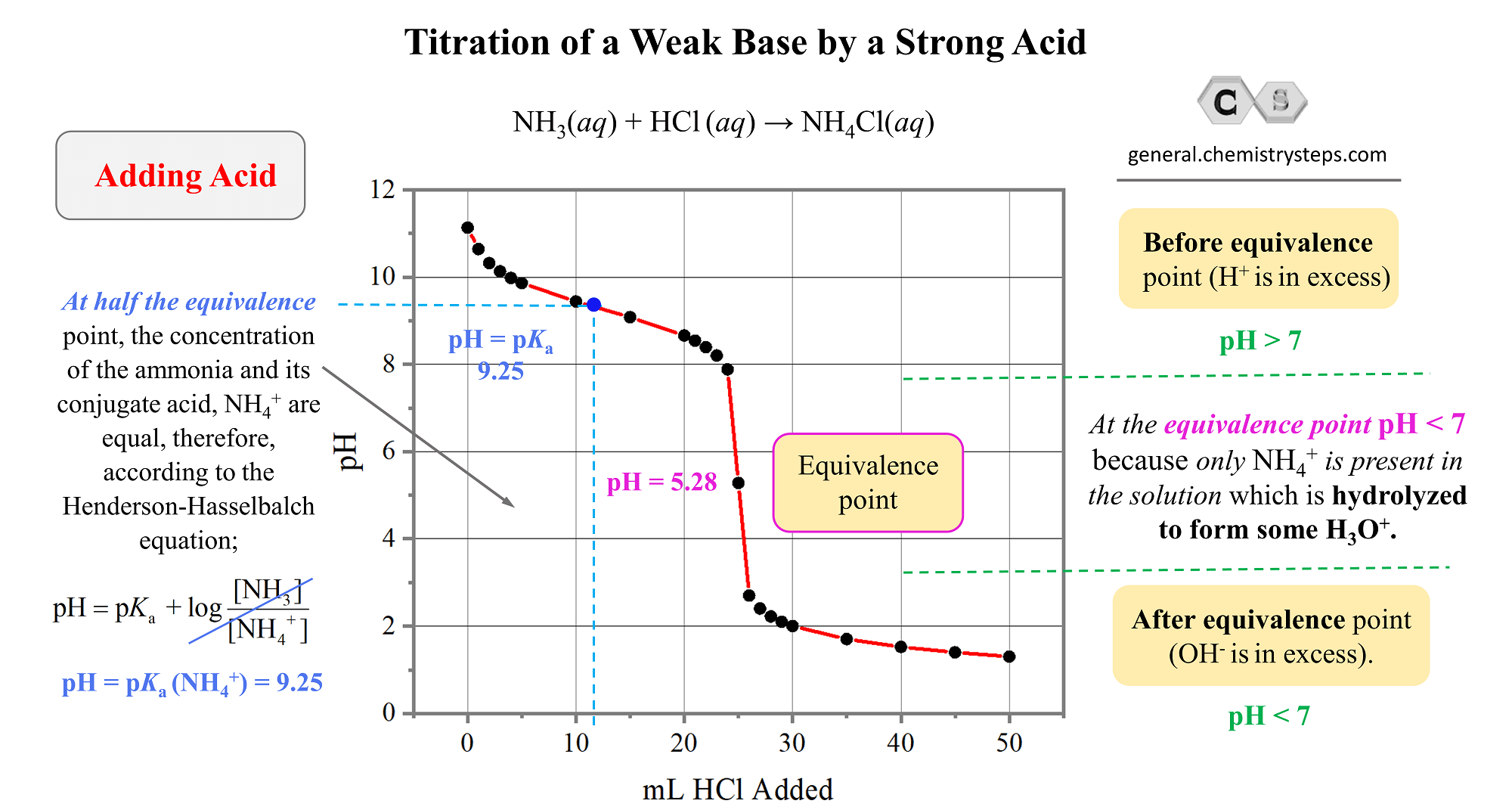

Computational tools now enhance titration precision: predetermined equivalence point algorithms, automated pH sensors, and real-time data logging reduce human error. Yet, the underlying chemistry remains rooted in equilibrium principles. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation—pH = pKa + log([A⁻]/[HA])—serves as a quantitative bridge, linking the acidity of the final buffer mixture to the acid dissociation constant.

This equation empowers chemists to calculate unknown weak acid concentrations with accuracy, transforming titration data into actionable analytical results.

Applications Across Science and Industry

Weak acid strong base titration finds broad utility beyond academic laboratories. In environmental science, it identifies acidic pollutants in water bodies by quantifying weak organic acids from industrial runoff. Pharmaceutical companies depend on titration to verify active ingredient purity and optimize formulation stability, especially for weak acid-based drugs like aspirin or penicillin derivatives.

Food and beverage industries apply the technique to measure acidity in preservatives, flavoring agents, and natural extracts, ensuring consistency and safety standards. Emergency response teams leverage titration to rapidly assess chemical spills, preventing harmful exposure through precise neutralization measures.

The method’s versatility extends to research, where it underpins kinetic studies, buffer creation, and reaction mechanism analysis. Despite its foundational nature, sufficient depth remains in optimizing conditions—temperature control, ionic strength adjustments, and efficient mixing—to minimize errors and enhance reproducibility.

Training chemists in these details not only improves data quality but also deepens understanding of acid-base interplay in real-world materials.

Mastering the Art of Pipetting and Indicator Selection

Success in weak acid strong base titration hinges equally on technical execution as on theoretical grasp. Accurate measurement begins with precise volumetric pipetting—using calibrated glassware to avoid dilution errors that skew concentration calculations. Even minor misapplications of pH indicators, such as methyl orange or phenolphthalein, can lead to inaccurate endpoints; phenolphthalein, for instance, signals the endpoint near pH 8.3, ideal for strong base-weak acid titrations but unsuitable for weaker systems requiring a sharper transition.

Careful compatibility checks between indicator color change and weak acid pKa ensure reliable visual detection.

Modern laboratories combine traditional indicators with advanced potentiometric methods, where automated pH probes deliver continuous monitoring with micro-SPD precision. These tools guard against human oversight, enhancing detection of subtle endpoints in complex mixtures. Together, meticulous technique and precise instrumentation elevate titration from a manual procedure to a pinnacle of analytical rigor.

The Enduring Relevance of Chemical Equilibrium

At its essence, weak acid strong base titration exemplifies how deep chemical principles drive practical science.

It translates the invisible dance of protons and electrons into measurable signals—pH shifts that speak volumes about molecular behavior. This fusion of theory and application reflects chemistry’s power: to decode nature’s complexity, one drop of titrant at a time. Whether safeguarding public health, protecting ecosystems, or advancing drug development, this method remains indispensable.

As analytical technology evolves, its core remains unshaken—a testament to the precision born from understanding weak acid strengths and strong base reactions.

Through careful control of reaction stoichiometry, precise endpoint detection, and informed use of indicators and data analysis, weak acid strong base titration delivers results of unmatched reliability. It stands not just as a technique, but as a benchmark for chemical accuracy—illuminating both the subtleties of molecular interactions and their far-reaching impact across science and society.

Related Post

Decoding Acid-Base Reactions: The Power of Weak Acid-Strong Base Titration

Investigating the Perpetual Impact of Sharon Case: A Daytime Icon

Alexa Dellanos Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Boyfriend

As₃: The Curious Neutron-Only Element Defying the Norm