No Fertilization, Asexual or Sexual — How Life Reproduces Without Mating

No Fertilization, Asexual or Sexual — How Life Reproduces Without Mating

In the vast tapestry of biological reproduction, the absence of fertilization is not a gap but a profound evolutionary adaptation, manifesting through both asexual and sexual mechanisms across the tree of life. While fertilization remains central to genetic diversity in many species, numerous organisms bypass it entirely, relying instead on asexual processes or having refined mechanisms that render classical fertilization obsolete. This biological duality challenges simplistic notions of reproduction and reveals nature’s ingenuity in ensuring survival even in the absence of mating.

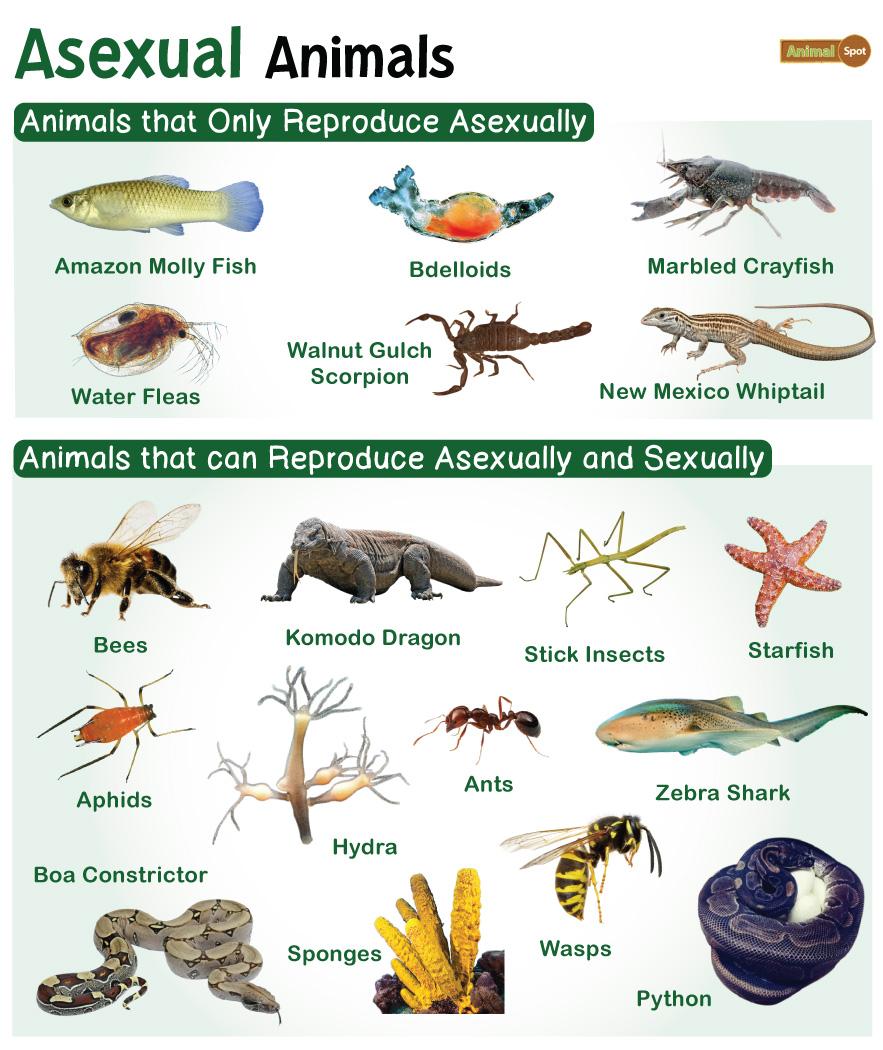

Asexual reproduction, present in organisms ranging from single-celled microbes to complex plants and invertebrates, allows rapid propagation without the need for a partner. Processes like binary fission, budding, and parthenogenesis enable organisms to pass on genetic material with precision and speed. As one evolutionary biologist noted, “Asexuality is nature’s shortcut—replication without compromise.” For example, bdelloid rotifers, microscopic animals found in temporary freshwater habitats, have long been considered “sterile” of sexual reproduction and have thrived for millions of years through clonal propagation, adapting to extreme environments without genetic mixing.

Despite its efficiency, asexual reproduction limits genetic variation, potentially reducing adaptability. This is where sexual reproduction steps in, introducing diversity through meiosis and recombination. Yet even in sexual species, fertilization is not always necessary.

Some organisms have evolved alternative pathways—such as automixis or apomixis—where genetic material is preserved or replicated without traditional mating. These mechanisms highlight a spectrum of reproductive strategies that illuminate how life persists across vastly different ecological niches.

Nature’s Dual Pathways: Asexual Regularity and Sexual Complexity

Sexual reproduction involves the fusion of gametes from two distinct individuals, fostering genetic recombination that fuels evolutionary innovation.

In contrast, asexual reproduction generates offspring genetically identical to the parent, ensuring the perpetuation of successful traits in stable environments. “It’s a trade-off,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a reproductive ecologist.

“Asexuality excels in velocity and energy efficiency, while sexual reproduction excels in plasticity and resilience.” Virufactured through simple cell division but capable of complex adaptations, asexual mechanisms thrive in predictable conditions. Yet in fluctuating or challenging habitats, sexual reproduction remains essential for long-term survival.

Examples of Striking Asexual Survival

Among the most compelling examples of asexual reproduction is the remarkable resilience of certain plant species. The popular houseplant *Pilea peperomioides* (the Chinese money plant) readily reproduces via offsets—genetically identical clones that detach from stem bases and root independently.

Similarly, quaking aspen groves consist of vast “clonal colonies,” where thousands of trees share identical DNA across miles of forest, uniting through根引 (root grafts) without fertilization.

- Bdelloid Rotifers: These microscopic animal critters have thrived for over 40 million years without sexual reproduction, relying on desiccation tolerance and DNA repair mechanisms to survive extreme conditions. "Their genome shows little evidence of sexual selection—evolutionary success without partners," observes David R. Bush.

"They challenge the dogma that sex is essential for life’s persistence."

- Komodo Dragons: In 2016, a population of Komodo dragons in Indonesia reproduced through parthenogenesis— Developing eggs without fertilization—when no males were available. This rare phenomenon demonstrated that some species retain the genetic machinery for sexual reproduction but can shift to asexual pathways under pressure.

- Parthenogenesis in Invertebrates and Reptiles: Compound parallelisms exist between insects, cephalopods, and certain reptiles. The New Mexico whiptail lizard, for instance, is entirely female and reproduces via parthenogenesis, forming a thriving population in arid regions where mating opportunities are scarce.

While no fertilization occurs in these cases, the mechanisms—whether automixis (a form of sexual recombination without mating), apomixis (asexual seed formation in plants), or environmental triggers favoring clonal reproduction—serve to maintain genetic integrity or spark novel variations through mutation. The distinction lies not in redundancy but in strategic specialization: asexual pathways dominate in ecological stability, while sexual reproduction accelerates adaptation in dynamic or hostile environments. < obstacles to fertilization, such as geographic isolation or extreme climates, often select for asexual strategies.

In Antarctica, for example, simple mosses and liverworts propagate clonally across frozen landscapes, bypassing the challenges of pollinator scarcity. Conversely, in biodiverse, densely populated ecosystems like tropical rainforests, sexual reproduction flourishes, allowing species to exploit ever-changing niches through genetic assortment. These divergent trajectories underscore a fundamental biological principle: reproduction adapts to necessity.

The boundary between formal fertilization and asexual survival is increasingly blurred. Emerging research reveals that some organisms switch reproductive modes based on environmental cues. Vertical gene transfer, horizontal DNA exchange, and even symbiotic partnerships now feature in the reproductive toolkit of select species, expanding the definition of what “reproduction” truly entails.

As one evolutionary geneticist remarked, “Life doesn’t panic over the absence of mating—it innovates.”

Understanding reproduction beyond fertilization reshapes perspectives on biodiversity, speciation, and extinction resilience. It reveals ecosystems not as static collections but as dynamic networks shaped by reproductive strategy. In a world grappling with rapid environmental change, the diversity of reproductive tactics—psychedelic in form but grounded in survival—offers clues to life’s enduring tenacity.

From lab-grown clones to wild rotifers defying sexual norms, nature’s answer to “no fertilization?” is a chorus of adaptive brilliance, each encoded in genes and shaped by evolution’s unrelenting drive to persist.

Related Post

Stephanie Buttermore Bio Age Wiki Net worth Height Ethnicity Boyfriend

Patrick Mahomes’ Salary: How the STL Quarterback commands $203 Million

Unveiling The Life And Journey Of Asonta Gholston: From Resilience to Renewal

Brookline: Where History, Nature, and Excellence Converge