1815 Tambora Eruption: What Went Wrong? The Volcanic Catastrophe That Shook the World

1815 Tambora Eruption: What Went Wrong? The Volcanic Catastrophe That Shook the World

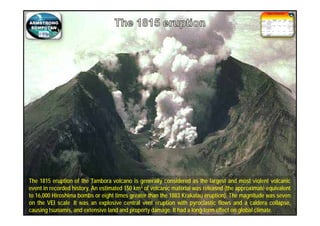

On a quiet afternoon in April 1815, Mount Tambora—then an obscure Indonesian peak—unleashed a cataclysmic eruption that shattered global climate patterns and altered human history. With a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 7, the blast was one of the most violent in recorded history, spewing trillions of tons of ash and gas into the atmosphere. The immediate devastation was catastrophic: entire villages vanished, lahars buried landscapes, and thousands perished in the blasts and pyroclastic flows.

Yet the true scale of the disaster unfolded not just locally, but across continents—igniting a year of extreme weather, crop failures, and social upheaval that became known as the “Year Without a Summer.” What began as geological violence morphed into a planetary crisis, revealing how one mountainous eruption could trigger cascading failures in climate, agriculture, and human stability. The eruption’s sheer force defied historical precedent. Modern estimates indicate Tambora expelled approximately 160 cubic kilometers of material, including rock and ash pulverized into fine particles that rose more than 50 kilometers into the stratosphere.

“The column of ash reached altitude where it was carried globally by winds, forming a reflective veil that dimmed sunlight," noted volcanologist Dr. Michael Sheridan, whose analysis of ice core data reveals the eruption’s ash signature—called a “volcanic winter fingerprint”—is detectable even today in polar ice sheets. This stratospheric veil triggered unseasonal frosts, prolonged cloud cover, and a dramatic drop in average global temperatures.

Geological records confirm the eruption’s explosive magnitude. Tephra layers cemented in sediment cores across Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean reveal ash fall numerous thousands of kilometers away. “The volume and dispersal of Tambora’s ejecta were unlike anything in the past millennium,” said Dr.

Rhodri Davies, a geophysicist specializing in historic eruptions. The resulting sulfate aerosols reflected solar radiation, plunging global temperatures by as much as 3°C in the months following April 1815—an abrupt climatic shock. The aftermath rippled far beyond the archipelago.

In Europe and North America, summer gave way to winter-like conditions: June and July of 1816 saw snowfall in New England, freezing temperatures in England, and persistent rain that turned fields into mud. Harvest failures followed: wheat yields in New York collapsed by over 75%, and potato blights struck Ireland just before the Great Famine’s broader devastation. “Corn came up late, grapes frozen, livestock starved—entire regions teetered on the brink,” documented early 19th-century journals.

Social and economic consequences followed rapidly. With food scarce and prices spiking, bread riots erupted in Switzerland and Japan. Grain shortages fueled migration, with desperate farmers seeking fertile land beyond their borders.

In Prussia, grain riots turned violent; in pitch-black winters, disease spread rapidly as weakened immune systems succumbed to cholera and typhus. Historian Susan Schulten frames the year as “a global stress test of society under extreme environmental pressure.” Multiple Fronts of Crisis: Climate, Agriculture, and Collapse The Tambora-induced climate anomaly triggered a domino effect across multiple domains. Climatologists have reconstructed the event using ice core proxies: levels of stratospheric sulfate soared, matching the eruption’s estimated magnitude.

The resulting “volcanic winter” lingered for 18 months, disrupting global weather systems from the tropics to the poles. Agricultural collapse was immediate and severe: - In New England, snow in June destroyed corn and vegetable crops. - In Ireland, grain failures predated the 1840s famine, weakening a population already vulnerable.

- In China, disrupted monsoon patterns led to dual disasters—floods in summer, droughts in autumn. Economically, the shock propagated through trade networks. Grain prices doubled in key European cities; urban poor faced starvation, while rural elites struggled to maintain control.

Social fabric frayed: desperation bred conflict, and governments—overwhelmed and underprepared—grappled with demands for relief. Historians emphasize how Tambora exposed the fragility of pre-industrial societies. Without modern weather forecasting, global supply chains, or emergency food reserves, communities lacked tools to respond effectively.

“The Mount Tambora eruption was not just a natural disaster—it was a social and climatic wrecking ball,” stated climate historian Dr. Naomi Oreskes. “It revealed how deeply human fate is tied to Earth’s volatile heartbeat.” In the decades that followed, societies began adapting: crop diversification accelerated in Europe, urban planning evolved in North America, and scientific inquiry into volcanology and climatology gained urgency.

Yet the ghost of Tambora endures—not as ancient lore, but as a stark reminder of nature’s unpredictable power and humanity’s vulnerability to forces far beyond control. Today, the 1815 eruption stands not only as a chapter in geological history, but as a cautionary tale: one volcanic blast, though distant, can reshape the world in ways unseen but deeply felt. The Tambora event reminds us that climate shocks—volcanic, solar, or human-caused—can cascade through ecosystems and societies with devastating speed.

And in an era of climate change, its lessons remain as urgent as ever.

Related Post

Iwu Student Admin Get In Touch For Quick Support: Your Fast-Lane to Academic Problem-solving

Meet Ladd Drummond: The Visionary Force Behind The Pioneer Woman Brand

How Hi5 Stands Out in the Evolving Social Media Landscape with Authentic Community Building

Exploring The Lives Of Michael Jordan’s Twins: Age, Legacy, and Beyond