Why “The Colossus Of The North”? The Monroe Doctrine and America’s Enduring Hemisphere Empire

Why “The Colossus Of The North”? The Monroe Doctrine and America’s Enduring Hemisphere Empire

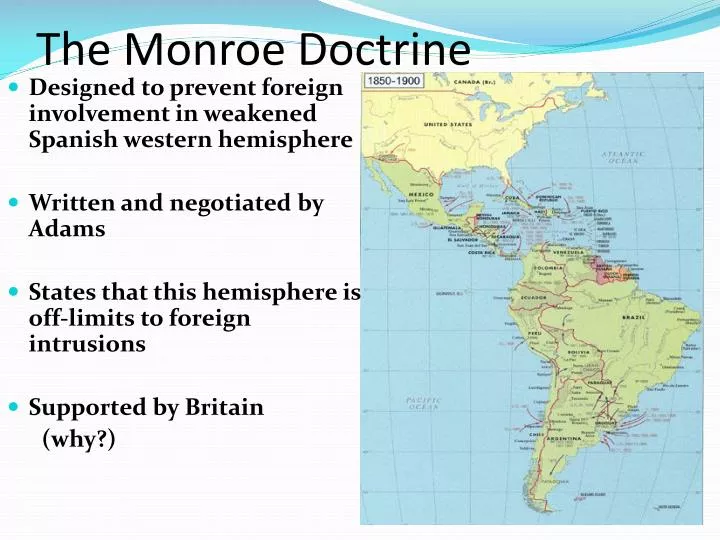

When timing, ideology, and power converge, a nation’s foreign policy transforms history. Nowhere is this more evident than in the legacy of the Monroe Doctrine, which cast the United States as the undisputed “colossus of the North” — a guardian of the Western Hemisphere with a self-styled mandate to shape the Americas. Since its proclamation in 1823, the doctrine has served not only as a diplomatic statement but as a defining framework for U.S.

hemispheric dominance, blending idealism with strategic hegemony. The doctrine emerged in a specific historical moment: a post-colonial Latin America freshly liberated from Spanish rule, yet vulnerable to European intervention—particularly Russian expansion southward and the specter of restored monarchy. President James Monroe declared: “The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have acquired, must be considered aflame with the ambition of liberty.” But beneath this bold warning to European powers lay a clearer message: the U.S.

would monitor the hemisphere as its exclusive sphere.

The Core Statement: “The Colossus Of The North”

The phrase “the colossus of the North” crystallizes the Monroe Doctrine’s assertion of U.S. supremacy.It evokes awe at America’s geographic scale and growing power, while encoding an unspoken claim to continental leadership. As historian знаход бондар once noted, the doctrine positioned Washington not merely as a regional actor but as the hemisphere’s independent arbiter—“the colossus that watches, intervenes, and ensures no foreign power undermines the Western Hemisphere’s destiny.” This metaphor was deliberate: “colossus” conveys both strength and inevitability. The U.S.

increasingly saw itself as the natural successor to imperial influence in the Americas, wielding economic leverage, diplomatic pressure, and military capability to enforce its vision of regional order. The doctrine’s original warning against European colonization—it declared, “We … view with feelings of congestion and voplasm every attempt by external powers to extend their system upon the lands of the New Improved World”—was layered with a quiet assertion of influence, blending idealism with strategic shielding.

Origins and Response: Building the Hemisphere Order

The Monroe Doctrine was forged not in a vacuum but through realpolitik.Britain’s naval dominance ensured enforcement, but President Monroe and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams crafted the doctrine’s ideological foundation to assert American sovereignty. At a time when European coalitions still threatened colonial restoration, Adams argued that the U.S., though young, now bore the imperial-like responsibility for its neighbors. Immediate responses varied.

Latin American leaders welcomed the warning against European re-colonization but remained skeptical of U.S. long-term intentions. Yet over decades, the doctrine evolved—from a defensive bulwark to a tool of influence.

By the late 19th century, under presidents like Taft and Roosevelt, its language shifted toward proactive intervention, justifying economic and military steps to “maintain order” in the region. The myth of the “colossus” returned—not just as a defender, but as the unmanaged force shaping Latin America’s destiny.

Today, the echoes persist: from Panama’s 1903 independence (allegedly engineered by the U.S.) to Cold War interventions framed as “hemispheric defense,” and modern diplomacy that invokes Monroe principles to counter external influence.

The “colossus” endures not as empire in the classical sense, but as a symbol of enduring U.S. authority over the Americas—an empire of influence, shaped by historical precedent and layered pragmatism.

Geopolitical Impact: From Warnings to Enforcement

The doctrine’s operationalization reshaped regional relations. The Roosevelt Corollary (1904) explicitly justified U.S.intervention to “steer” “mismanaged” nations, transforming defensive logic into active policing of Latin America. This expansion entrenched the “colossus” image, embedding interventionism into American statecraft. Economically, the doctrine facilitated infrastructure and trade dominance—states dictated to secure access and stability.

Militarily, it legitimized occupation and bases, from Cuba to Grenada. Politically, it pressured governments to align with Washington, often destabilizing democratic processes in favor of strategic loyalty.

These actions cemented a paradox: a self-proclaimed guardian of sovereignty, yet frequently the architect of intervention.

The “colossus” name captures this duality—protector and patron, sovereign and overseer.

Modern Relevance: The Echoes of Hemispheric Supremacy

In the 21st century, the Monroe Doctrine’s legacy remains vivid, though less explicitly invoked. Contemporary U.S. policy continues to frame regional cooperation through a hemispheric lens—addressing migration, drug Trade, and security in frameworks that recall Monroe’s hemispheric guardianship.When the U.S. champions regional bodies like the Organization of American States, it draws, consciously or not, from the doctrine’s foundational premise: collective security within defined American interests. Yet Latin America’s growing multipolarity—engagements with China, Russia, and the EU—challenges U.S.

primacy. Former leaders and scholars debate whether the “colossus” still leads or merely resists obsolescence. While territorial control faded, influence endures through economic partnerships, diplomatic pressure, and soft power.

The “Colossus” Reimagined: Legacy and Labor

The “colossus of the North” endures not in statues or territory, but in narrative—shaping how power is perceived across the hemisphere. The Monroe Doctrine’s greatest impact lies in its fusion of moral declarations with strategic ambition, creating a hemispheric identity where U.S. preeminence is both justified and contested.This legacy is neither wholly heroic nor purely hegemonic. It reflects a nation grappling with its role: as protector against foreign ambition, as economic architect, and at times, as unilateral intervenor. The “colossus” endures because it captures an enduring truth: in international relations, location, endurance, and perception define power as much as force.

Through the lens of Monroe Doctrine, the United States remains the hemisphere’s preeminent actor—though now navigating a world where “colossal” status demands adaptation, resilience, and negotiation amid evolving global dynamics.

Conclusion: America Examines the Mirror of Power

The “colossus of the North” is more than a nickname—it is a lens through which to understand the enduring U.S. commitment to shaping its hemisphere.From David Monroe’s 1823 warning to modern diplomatic currents, the doctrine has evolved but retained its core: the belief that the Americas belong to the Americas, under U.S. watch. Whether as architect or antagonist, the “coloss

Related Post

Jill Wagner: From Broadway Stages to Television Stardom — A Multifaceted Force in Screen and Stage

BoxBoy Bio Age Wiki Net worth Height Girlfriend or Single

NYC Property Tax A Comprehensive Guide: Demystifying the Cities Most Complex Fiscal Landscape

Did Andrea Brillantes and Daniel Padilla Date? A Deep Dive into Their Relationship and Public Heartbeats