When Boiling Becomes a Scientific Threshold: Why 100°C Is the Kelvin Tipping Point

When Boiling Becomes a Scientific Threshold: Why 100°C Is the Kelvin Tipping Point

Boiling water at 100°C—commonly accepted at sea level—is not just a household observation; it represents a critical thermodynamic milestone defined by the Kelvin scale. At this precise temperature, water undergoes a phase change where hydrogen bonds break sufficiently to vaporize into steam, a process that defines the boiling point in physics and engineering. But this moment transcends everyday experience—when expressed in Kelvin, the boiling point marks a fundamental boundary where energy, entropy, and molecular behavior align in a precise scientific framework.

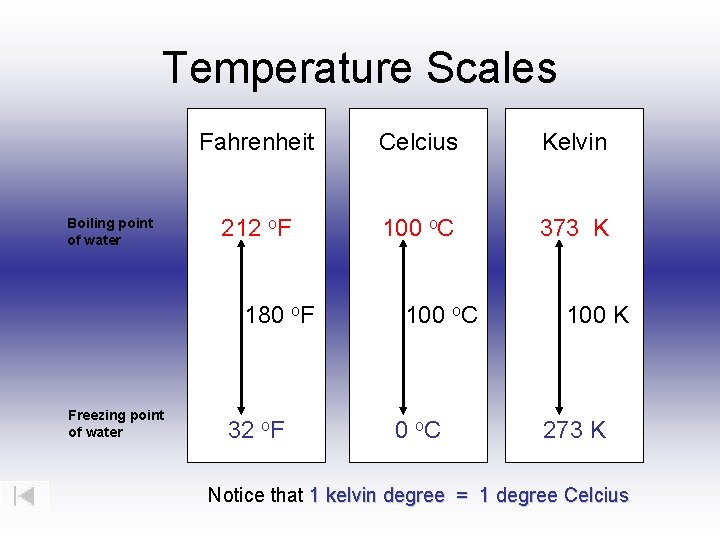

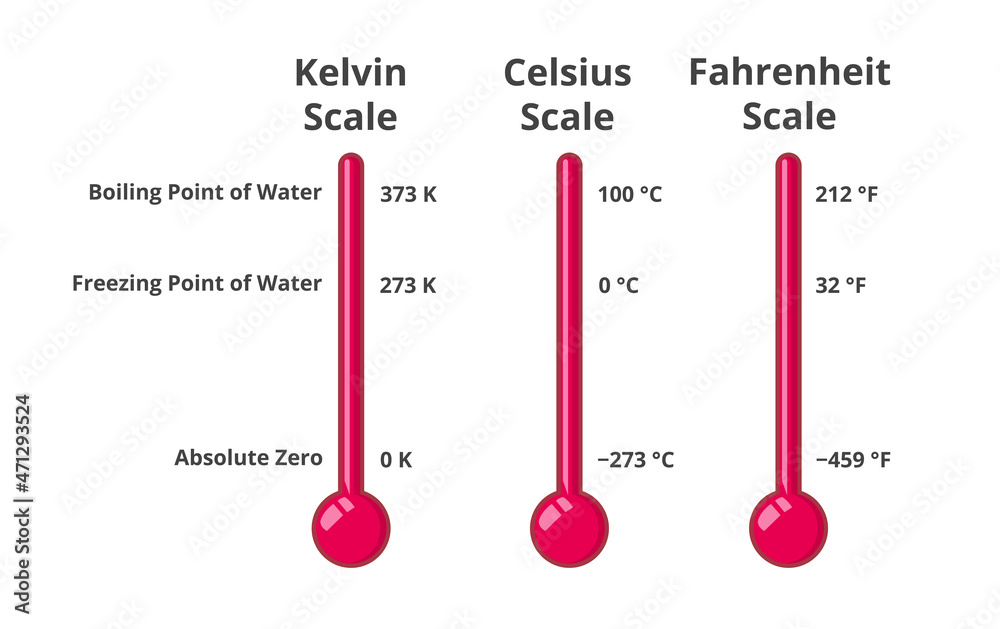

The boiling point of water in Kelvin is exactly 373.15 K, a value derived directly from the Kelvin scale’s foundation: absolute zero, zero Kelvin, where molecular motion ceases. Unlike Celsius, which resets at the freezing point of water (0°C), or Fahrenheit, built on arbitrary human-centric divisions, Kelvin offers an unbroken scale with meaningful physical significance. “373.15 K is the moment molecular kinetic energy overcomes intermolecular forces consistently across pure water,” explains Dr.

Elena Torres, thermodynamics specialist at MIT. “It is not just a number—it is a threshold where phase equilibrium becomes irreversible under standard atmospheric pressure.” Understanding boiling in Kelvin reveals deeper insights into thermodynamic behavior. At 373.15 K, water’s vapor pressure matches atmospheric pressure, enabling bubbles of vapor to form within the liquid—a defining criterion of boiling.

This transition is governed by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which quantifies how pressure and temperature influence phase changes. “The Kelvin scale allows precise calculation of these relationships without confusion from freezing or melting points,” notes Dr. Torres.

“It’s not just about how hot it feels—it’s about energy states in a statistically predictable system.” Temperature in Kelvin is directly proportional to absolute degrees, making it indispensable in scientific modeling. For example, steam turbines, refrigeration cycles, and chemical reactors rely on Kelvin to calculate heat transfer efficiency and reaction kinetics. “Engineers cannot afford imprecise references when designing systems dependent on boiling,” observes mechanical engineer James Kwon.

“Using 373.15 K ensures consistency in thermal calculations, reducing risk and improving performance.” Hydrogen-bonded cohesion defines water’s behavior, and at 373.15 K, this molecular framework destabilizes. Each water molecule gains enough thermal energy—approximately 69.8 kJ/kmol—to overcome lattice-like attractions. This energy threshold means boiling is not merely heating, but a quantifiable disruption of intermolecular order.

Physicists often emphasize: “Boiling at 373.15 K reflects a universal balance—where energy input triggers predictable, irreversible change.” Interestingly, the boiling point varies with pressure. At sea level (1 atm), water boils at 100°C (373.15 K), but at higher elevations—such as on Colorado’s mountains—where atmospheric pressure drops, the boiling point drops below 100°C. Conversely, in autoclaves under pressurized steam, boiling exceeds 373.15 K, demanding careful engineering controls.

“The Kelvin value is not immutable; it anchors our understanding of standard conditions,” explains Dr. Maria Lopez, a thermal process expert. “It provides a benchmark for comparison across climates and engineering systems.” Water’s boiling point in Kelvin also holds significance in climate science and planetary study.

On Mars, where atmospheric pressure averages just 0.6% of Earth’s, water boils below 100°C—often near 250–270 K. This affects atmospheric chemistry and informs models of potential liquid water stability on extraterrestrial surfaces. “Understanding boiling in Kelvin helps us predict phase changes far beyond Earth,” notes planetary scientist Dr.

Rajiv Mehta. “It’s not only terrestrial—it’s fundamental to comparative planetology.” Historically, Celsius’s scale, established in the 18th century, reflects human comfort at 100°C, but Kelvin reveals the deeper physical reality. The Celsius-to-Kelvin conversion—subtracting 273.15—translates a scale reset into a discovery of absolute thermodynamic limits.

“This is more than a conversion,” says Dr. Torres. “It’s physics made visible: the point where liquid water becomes vapor under equilibrium conditions.” Backed by precise measurement and thermodynamic rigor, 373.15 K stands as a benchmark.

It defines not just a temperature, but a limit of molecular behavior governed by energy, pressure, and entropy. In industrial boilers, laboratory experiments, and planetary science, this number ensures consistency, accuracy, and predictability. Beyond its numerical precision, the boiling point in Kelvin embodies a gateway understanding: how a familiar phenomenon is rooted in absolute thermodynamics.

Mastery of this threshold enables better technology design, deeper scientific insight, and clearer communication across disciplines. In the quiet word “373.15,” science speaks with unmistakable clarity.

Related Post

Top Free Drawing Apps for Android That Let You Draw On the Go—No Cost, Maximum Creativity

Lackawanna Pro Bono: Bridging Justice Gaps in One of America’s Most Underserved Communities

Exploring Alternatives to Gorecenter: What Sites Truly Deliver in the Online Marketplace

A Closer Look at Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's Dentition: A Study