What Is the Protein Monomer? The Tiny Building Blocks That Shape Life

What Is the Protein Monomer? The Tiny Building Blocks That Shape Life

At its core, every protein is a molecular marvel assembled from repeating subunits known as monomers—specifically, amino acids. These protein monomers are not mere ingredients but the fundamental structural components that, when precisely linked, give rise to the diverse and dynamic proteins essential for nearly every biological process. Understanding the nature of the protein monomer illuminates how life’s complexity emerges from simple biochemical units, revealing the elegant design behind cellular function.

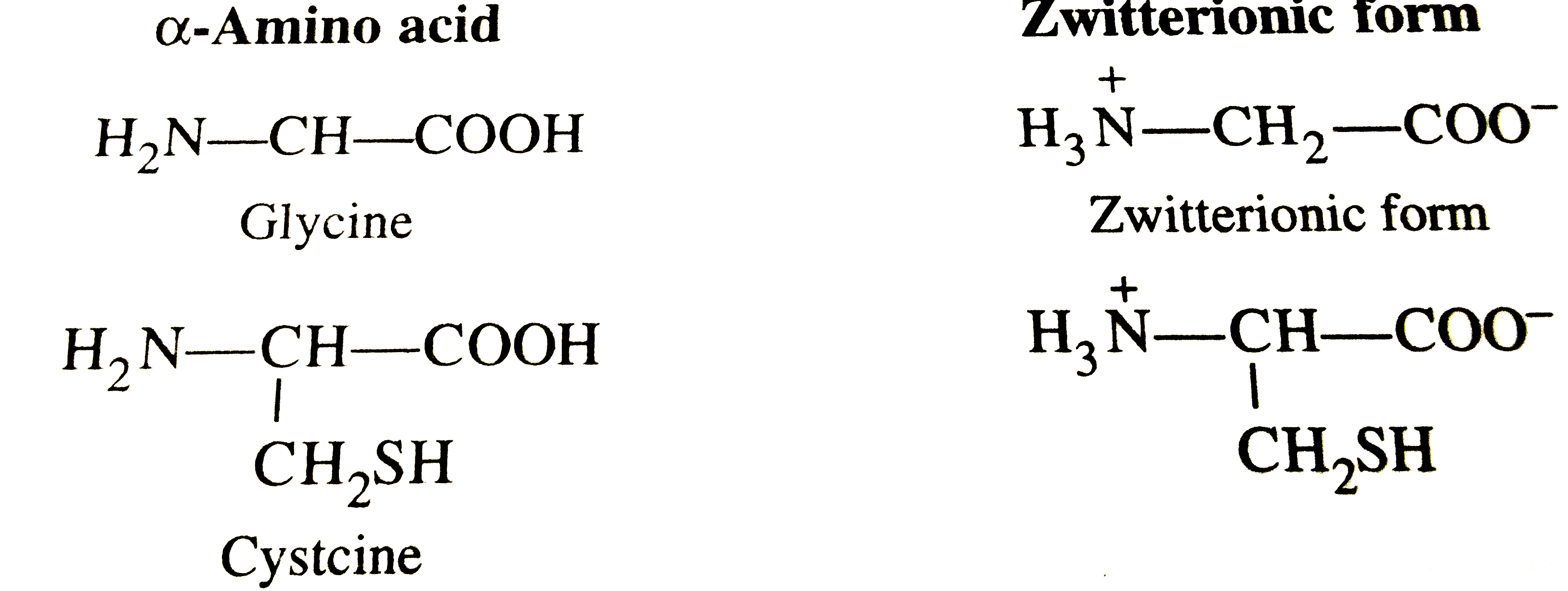

Protein monomers are amino acids, organic molecules featuring a central carbon atom bonded to an amino group (—NH2), a carboxyl group (—COOH), a hydrogen atom, and a distinctive side chain (R group). The specificity of each monomer’s R group determines its chemical behavior and role within proteins. As declared by biochemist Linus Pauling, “Proteins are synthesized from amino acids arranged in precise sequences, forming the intricate machinery of the cell.” This concept underscores the monomer’s critical identity: more than isolated units, they are the genetic and structural essence encoded into life.

The formation of a protein monomer begins in the cellular machinery of ribosomes, where mRNA instructions guide the stepwise assembly of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Each bond forms through a condensation reaction, releasing a water molecule and creating a stable connection. This mechanism ensures amino acids are bonded in a specific linear sequence—what biologists call the primary structure.

Without correctly positioned monomers, proteins cannot fold into functional three-dimensional shapes necessary for activity. In essence, the monomer is the irreplaceable unit upon which protein identity and function are built.

Types of Protein Monomers and Their Structural Significance

While all proteins are composed of amino acid monomers, not all monomers are alike—variations in their R groups yield distinct chemical properties and functional roles.Broadly, protein monomers fall into four key classes based on amino acid characteristics: aliphatic, aromatic, acidic, and polar.

Aliphatic monomers—those with nonpolar, hydrocarbon-based side chains—tend to be hydrophobic and drive protein folding by avoiding water, stabilizing cores within globular proteins. These include amino acids like glycine and alanine, crucial for creating compact, stable protein structures.

In contrast, aromatic monomers such as phenylalanine and tyrosine feature ring-shaped side chains that contribute rigidity and ability to interact through π-stacking, important for signaling and enzyme binding. Acidic monomers—glutamate and aspartate—possess negatively charged side chains at physiological pH, enabling ionic interactions and roles in nutrient transport and enzyme catalysis. Finally, polar monomers like serine and threonide, with side chains capable of hydrogen bonding, mediate hydration and functional site specificity.

Each monomer’s unique chemical signature influences how it integrates into the protein’s architecture. For instance, proline—a unique aliphatic amino acid with a cyclical structure—often introduces bends or kinks in protein chains, allowing for sharp structural transitions vital in collagen and enzyme active sites. This diversity ensures monomers collectively contribute to the nuanced folding, stability, and biological activity characteristic of each protein.

Functions Enabled by Protein Monomers: From Catalysts to Structural Supports

The versatility of protein monomers underpins their wide-ranging biological functions, ranging from metabolic catalysis to structural reinforcement. Enzymes, responsible for accelerating biochemical reactions, rely on carefully selected monomers arranged into complex architectures—each monomer occupying precise positions to bind substrates and facilitate transitions. Take lysozyme, an enzyme in tears and saliva, whose function depends on amino acids configured in a catalytic pocket shaped by specific side-chain interactions.Transport proteins illustrate another dimension of monomer action. Hemoglobin, for example, depends on globin chains built from specialized monomers to bind oxygen and deliver it efficiently throughout the body. Its heme groups—iron-containing molecules—are anchored by conserved monomers, enabling precise molecular recognition.

Structural proteins such as keratin, found in hair, nails, and skin, derive strength from homopolymers rich in cysteine monomers. Disulfide bonds formed between cysteine residues create durable networks, conferring resilience and resistance to mechanical stress.

Regulatory proteins and signaling molecules further highlight monomer adaptability.

Receptor proteins on cell surfaces use specific combinations of amino acids to detect external signals and trigger internal responses. Industry and medical research increasingly harness engineered monomers to design novel proteins with tailored functions—from targeted drug delivery to industrial enzymes optimized for extreme conditions. This functional plasticity confirms the monomer’s central role in nature’s biochemical innovation.

Synthesis and Cellular Assembly: The Machinery Behind the Monomeric Chain

The formation of functional proteins begins with amino acid monomers, synthesized either within cells or obtained from dietary sources. In eukaryotic organisms, amino acids are either manufactured de novo through enzymatic pathways or sourced from ingested proteins broken down during digestion. Core amino acids such as glutamine and aspartate are commonly synthesized in muscles, whereas others like lysine and tryptophan must be absorbed from food—underscoring nutrition’s role in protein formation.Once available, amino acids enter the ribosome, the molecular factory where protein synthesis unfolds. mRNA serves as the template, directing the arrival of amino acids in sequence according to codon instructions. Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules, each carrying a specific monomer, recognize codons via their anticodon sequences and deliver the correct amino acid to the growing polypeptide chain.

Peptide bonds form between adjacent monomers, extending the protein Thread by one residue at a time.

Post-synthetic processing further refines protein functionality, with chaperone proteins assisting correct folding and modifications such as phosphorylation or glycosylation added to fine-tune activity. This intricate assembly process ensures the linear chain of monomers achieves a defined three-dimensional conformation—critical for biological performance.

Without precise monomer delivery, sequence accuracy, and folding coordination, the resulting polypeptides lose functionality and may even become harmful—linking monomer integrity to cellular health.

In industrial biotechnology, scientists manipulate these biological mechanisms to produce recombinant proteins using engineered organisms or cell-free systems. By selecting specific monomers, researchers tailor proteins for enhanced stability, catalytic efficiency, or therapeutic targeting, demonstrating the profound control achievable through understanding monomer chemistry.

The Cellular and Evolutionary Significance of Monomers

The reuse of a single amino acid monomer to build countless protein varieties speaks to evolution’s efficiency and innovation. From simplest enzymes to complex hormonal systems, the modular use of alanine, leucine, and other conserved monomers illustrates nature’s penchant for minimal yet powerful building blocks. This economy of design reduces genetic complexity while enabling functional diversity—a principle central to life’s adaptability.Studying protein monomers also enhances our grasp of disease mechanisms. Mutations altering a single amino acid can disrupt folding or function, causing pathogenic conditions such as sickle cell anemia—where a single change in hemoglobin’s monomeric chain transforms red blood cells. Similarly, misfolded amyloid proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease reveal how monomeric abnormalities cascade into structural defects and neurodegeneration.

Ultimately, the protein monomer is more than a biochemical unit—it is the cornerstone of biological complexity. Recognizing its role fosters deeper understanding of physiology, medicine, and biotechnology, reinforcing how the smallest molecular components orchestrate life’s most vital processes. As science continues to decode these molecular stories, the protein monomer remains a key to unlocking nature’s deepest engineering principles.

Related Post

The Highest Football Stadium in the World: A Monument to Thrill, Turf, and Towering Grandeur

Zackary Arthur Movies Bio Wiki Age Chucky Greys Anatomy and Net Worth

Eternal Mangekyō: The Ultimate Power Unleashed in Naruto’s Mystical Abyss

The Profound Power of the Math Symbol “∈”: Decoding Meaning, Structure, and Everyday Impact