What Is the Definition of a Food Analog? Unmasking the Science Behind Taste and Texture

What Is the Definition of a Food Analog? Unmasking the Science Behind Taste and Texture

In a culinary landscape increasingly shaped by innovation and necessity, the concept of a food analog has emerged as a pivotal bridge between traditional gastronomy and modern food science. True to its name, a food analog is a substance or product designed to mimic the sensory experience—flavor, texture, appearance, and even mouthfeel—of a real food, often replacing it in configurations driven by health, sustainability, or accessibility concerns. Far more than a substitute, a food analog represents a sophisticated integration of chemistry, biology, and culinary artistry aimed at preserving the authentic experience of eating while addressing contemporary challenges.

Defined with precision, a food analog is a manufactured or naturally derived ingredient intentionally formulated to replicate key attributes of a natural food.

These attributes include taste—captured through specific flavor compounds—texture, achieved via protein structures or fiber matrices, color achieved through natural pigments, and aroma, engineered to stimulate olfactory receptors similarly to the original. “A successful food analog doesn’t just imitate—it evokes,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a food technologist at the Institute for Sensory Food Science.

“It’s not about perfection, but about convincing the brain that what it’s experiencing is familiar—sometimes even indistinguishable.”

The Core Attributes That Define a Food Analog

At the heart of every food analog lie four essential components:

- Flavor Mimicry: Utilizing precise combinations of taste molecules—umami, sweetness, bitterness, and savoriness—food analogs replicate the dynamic flavor profile of authentic ingredients. Advanced techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry allow scientists to identify volatile flavor compounds found in meats, cheeses, or fruits, then synthesize or extract matching molecules.

- Textural Fidelity: Texture plays a crucial role in how food is perceived. The chewiness of a steak substitute, the flakiness of a baked pastry alternative, or the creaminess of a dairy-free sauce each rely on specialized processing—such as extrusion, gelation, or enzymatic modification—to produce mouthfeel comparable to natural counterparts.

- Visual Identity: Appearance shapes the first impression of any dish.

Colorants derived from spirulina, beetroot, or turmeric, combined with strategic layering and shaping, ensure analogs visually match real foods, triggering immediate recognition and psychological comfort.

- Aromatic Resonance: Smell enhances taste perception by up to 80%, according to sensory research. Food analogs incorporate aromatic compounds released during cooking—like savory Maillard reactions or roasted nut notes—to trigger authentic olfactory responses and deepen flavor authenticity.

Applications Across the Food Industry

Food analogs span a broad spectrum of uses, each tailored to specific consumer and industrial needs:

- Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods rely heavily on food analogs. Their products combine pea protein with heme—an engineered molecule that delivers a meaty flavor—alongside texturized fibers to replicate muscle structure.

The result is a burger that sizzles, bleeds (mimicking blood), and chews like beef.

- Allergen-Free and Diabetic-Friendly Formulations: For individuals with allergies, intolerances, or metabolic conditions, food analogs remove problematic proteins (e.g., gluten, casein) while preserving sensory appeal. Vegan cheeses made from tapioca, cashews, and cultured microbes deliver melt and stretch without dairy.

- Nutritional Fortification: School lunch programs and emergency food supplies often use food analogs fortified with vitamins and minerals. Pea protein powders or algae-based spirulina blends enhance protein content without altering taste or texture significantly.

- Sustainable Seafood Substitutes: As oceanic stocks decline, analogs made from soy, mushrooms, or seaweed-based gels mimic fish texture and briny flavor, offering eco-conscious consumers a familiar dining experience.

The Science Behind Sensory Convinction

Developing a high-fidelity food analog demands interdisciplinary expertise.

Food scientists blend biochemistry, food engineering, and sensory science to decouple desirable traits from problematic ones. For example, while cow’s milk delivers rich creaminess and encapsulated fats, a successful plant-based analog may use a blend of modified starches and micelle-like protein complexes to replicate that mouthfeel. “It’s not about copying everything perfectly—it’s about calibrating for what matters most to the consumer’s sensory journey,” emphasizes Dr.

Marquez.

Sensory panels play a critical role, evaluating analogs across smell, taste, texture, and visual appeal using standardized tasting protocols. Advanced tools—such as electronic noses, texture analyzers, and gas chromatographs—provide objective data to refine formulations, ensuring consistency across batches and brands.

Market Growth and Consumer Perception

Related Post

Torrey DeVitto Movies Bio Wiki Age Paul Wesley Vampire Diaries and Net Worth

Marvin Gaye’s Sexuality: A Raw Force Behind a Legend’s Iconic Artistry

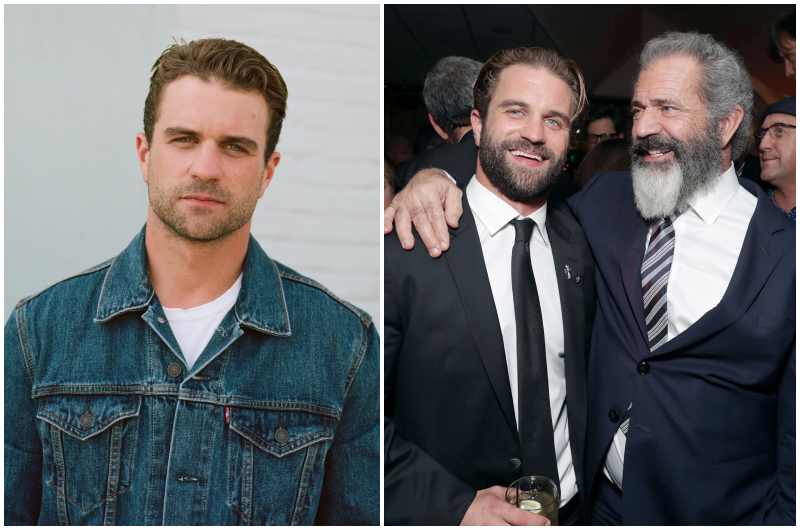

Mel Gibson’s Wives and Children: A Deep Dive into Family, Faith, and Controversy

Julia Hart Drops Seductive Photos After Dark AEW Character Change