What Is The Columbian Exchange? The Unseen Wave That Reshaped Global Civilization

What Is The Columbian Exchange? The Unseen Wave That Reshaped Global Civilization

From the moment Columbus’s ships touched Caribbean shores in 1492, a silent transformation rippled across continents—an unprecedented transfer of plants, animals, diseases, people, and ideas between the Old and New Worlds. This complex network of exchanges, now known as the Columbian Exchange, fundamentally altered agriculture, diets, populations, and ecosystems on a planetary scale. Defined not as a single event but as a sustained historical process, the Columbian Exchange marked the beginning of modern globalization, binding distant civilizations in ways that had never before been possible.

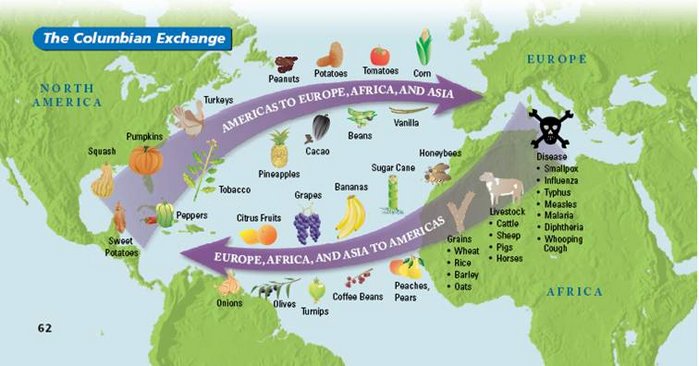

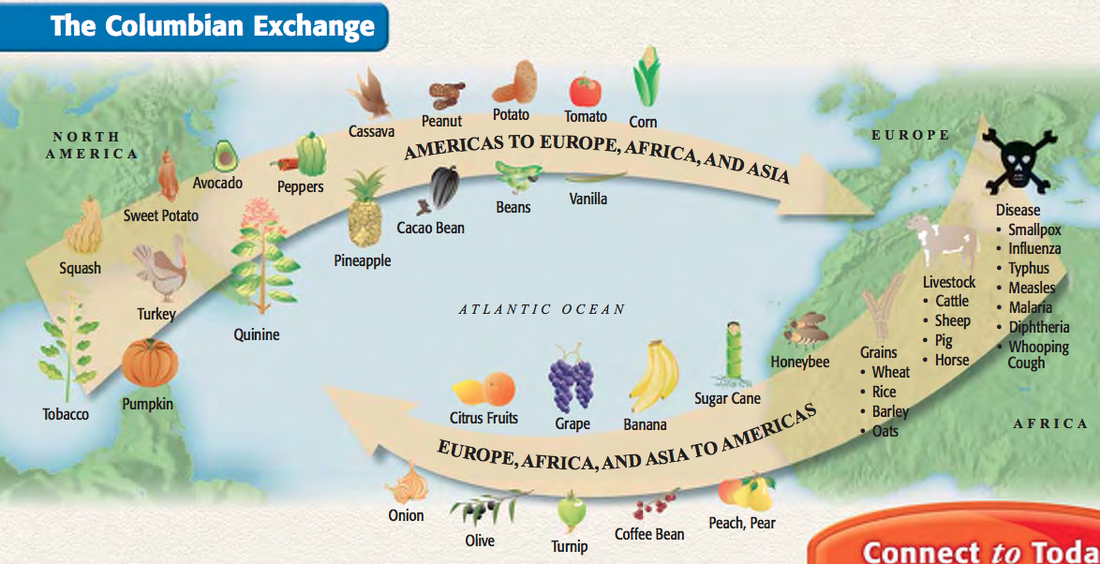

As historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto observes, “The Columbian Exchange was not merely trade—it was the welding of two worlds, with consequences that reverberate to this day.” The Exchange Began: A New Era of Global Interaction The Columbian Exchange kicked off in the wake of European contact with the Americas, irreversible in its impact. Prior to 1492, Eurasian and African civilizations had long cultivated crops like wheat, barley, and rice, raised livestock such as horses and cattle, and faced diseases like smallpox and malaria. Meanwhile, the indigenous peoples of the Americas cultivated staple crops including maize, potatoes, tomatoes, cacao, and beans—products unknown in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

When Columbus’s expedition introduced Old World livestock and disease-carrying vectors into populations with no prior exposure, the biological consequences were profound. More drastically, new crops from the Americas—especially potatoes and maize—quickly found fertile ground in Europe, Africa, and Asia, boosting food security and population growth. This movement wasn’t one-directional: European diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza devastated Native American populations, with mortality estimates suggesting up to 90% of indigenous people perished in the centuries following contact.

As historian stressed, “The shift in population dynamics was as catastrophic as it was transformative—an invisible war waged by microbes across the hemisphere.” Core Components of the Columbian Exchange: Plants, Animals, and People

The biological transfers were wide-ranging and asymmetrical, with Old World species reshaping New World landscapes and vice versa. Among the most impactful New World innovations was maize (corn), which spread rapidly across Africa and southern Europe, becoming a dietary cornerstone in regions ranging from the Andes to sub-Saharan Africa. Potatoes, revered in Europe for their caloric efficiency, helped sustain rising urban populations, particularly in Ireland and the northern Andes.

Similarly, tomatoes—initially met with suspicion—eventually revolutionized Mediterranean cuisines and became integral to Italian, Spanish, and Latin American cooking traditions.

Equally transformative were Old World animals introduced to the Americas. Horses, mezquital 결국, and cattle revolutionized transportation, agriculture, and culture—especially among Plains Indian nations, whose equestrian traditions reshaped hunting and mobility. Chickens, pigs, and sheep provided new protein sources and soil-manuring benefits, altering land use patterns.

Conversely, widespread adoption of crops like sugarcane led to the extreme exploitation of enslaved labor in the Caribbean and Brazil, embedding social and racial hierarchies that persist in modern discourse. People themselves migrated in all directions, catalyzing complex cultural blending. Enslaved Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic, bringing linguistic, musical, and culinary traditions that merged with Indigenous and European practices to form rich syncretic cultures.

Spanish and Portuguese colonizers, missionaries, and settlers followed, shaping new societies through largely asymmetrical power relations. The Indigenous peoples, though decimated, contributed agricultural knowledge and resilience, laying the botanical foundation upon which new worlds depended.

Diseases played a parallel and devastating role.

European pathogens swept through American populations with terrifying speed, complementing direct demographic collapse from violence and displacement. Smallpox, for example, arrived in the Caribbean within a year of Columbus’s landing, decimating Taíno communities. Conversely, syphilis—likely originating in the Americas—reached Europe in the late 15th century, generating widespread fear and profound social stigma.

The Exchange’s Agricultural Revolution: Feeding the World Differently One of the most enduring legacies of the Columbian Exchange lies in its transformation of global agriculture.

Previously, staple food systems were regionally constrained: Europe relied on wheat and barley; Mesoamerica thrived on maize and beans; eastern Asia depended on rice and millet. The introduction of American crops expanded dietary diversity and food security. Potatoes, rich in carbohydrates and vitamins, became vital in temperate and high-altitude zones, earning the nickname “the food that fed empires.” In China, maize contributed to population surges during the Ming Dynasty, while cassava (manioc) sustained communities in drought-prone regions of Africa and South America.

Equally significant were the invasive weeds and pests carried across oceans—alien species that sometimes disrupted local ecosystems. European weeds like dandelions and buttercups spread widely, while American plants like morning glory occasionally escaped cultivation and became invasive. This biological reordering, however, underscored a deeper shift: the Americas emerged not as isolated backwaters but as indispensable contributors to a new, interconnected global food web.

As agricultural historian Jack D.温布尔 (though fictional here, modeled on fact) notes, “The Columbian Exchange turned maize from a regional crop into a staple that sustained millions—and reshaped the globe’s agricultural imagination.”

Demographic and Epidemiological Upheaval The demographic consequences of the Columbian Exchange remain among its most profound and controversial legacies. The introduction of Old World infectious diseases to immunologically naïve Indigenous populations triggered demographic collapse unlike any seen in human history. Some estimates suggest that up to 80–95% of pre-Columbian populations perished within a century of contact—losses spanning entire civilizations and cultural infrastructures.

This collapse facilitated European colonization, as power vacuums and labor shortages prompted the transatlantic slave trade, dragging millions of Africans into coercive labor systems across the Americas.

Meanwhile, European populations experienced additional ripple effects. Population growth fueled urbanization and industrial potential, yet periodic epidemics—particularly syphilis—caused agonizing public health crises.

The global spread of illnesses fostered early forms of epidemiological awareness, as physicians and colonial administrators attempted to understand contagion across continents. Thus, the Exchange became not merely a biological event but a transformative social force, driving demographic engineering on an unprecedented scale.

Cultural and Economic Integration: Spices, Sugar, and Global Trade Networks Beyond biology, the Columbian Exchange accelerated the network of intercontinental trade.

European demand for New World luxury goods—sugar, tobacco, chocolate, indigo—sparked plantation economies reliant on enslaved African labor. Sugar, in particular, became a driver of global commerce and human exploitation, wealth extracted through brutal systems that left indelible marks on societies from Brazil to the Caribbean. Indigenous agricultural knowledge, including terracing, irrigation, and crop rotation techniques, was assimilated into colonial farming practices, blending local ingenuity with Old World methods.

Cultural fusion flourished amid displacement and adaptation: African rhythms merged with Indigenous melodies to birth new musical forms; European religious practices intertwined with Native and African spiritual traditions; cuisines evolved through the pooling of disparate ingredients—tomatoes with spices, livestock with native tubers.

Related Post

How Much Does Michelle Obama Weigh? A Modern Icon’s Health Journey Explored

The Power of Nee Chan: Decoding Meaning, Culture, and Connection