What Is a Trophic Level? The Hidden Foundation of Every Ecosystem

What Is a Trophic Level? The Hidden Foundation of Every Ecosystem

<

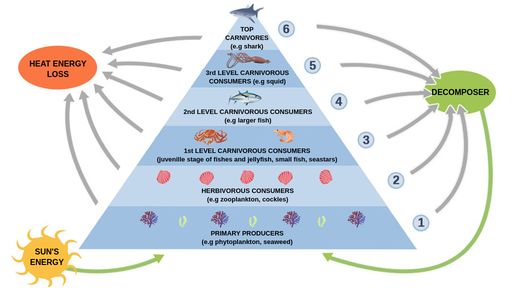

From microscopic phytoplankton to towering apex predators, each species plays a defined role, transforming solar energy into biomass across distinct consumption tiers. Understanding trophic levels is essential to grasping ecosystem dynamics. The concept was first formalized in the early 20th century by ecologists seeking to quantify energy flow beyond isolated predator-prey interactions.

As biologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson aptly stated, “Trophic levels represent the empirical backbone of food web analysis, revealing patterns invisible to casual observation.” They offer a structured lens through which scientists measure energy transfer efficiency, nutrient cycling, and ecological stability—foundational tools for conservation and environmental management.

The Seven-Layer Architecture of Energy Flow

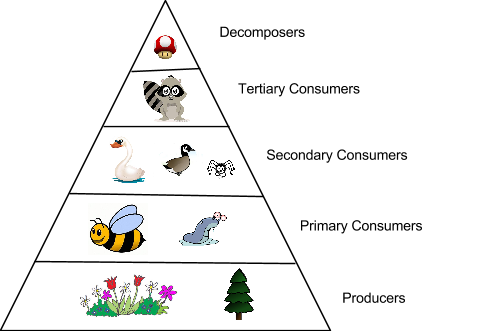

Trophic levels are traditionally divided into seven clear strata, though variations exist depending on ecosystem complexity.Each layer represents a step in the energy consumption chain: - **Level 1: Primary Producers** – Green plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria form the base, converting sunlight into organic matter. "Without producers, life as we know it collapses," scientists emphasize, highlighting their irreplaceable role in driving energy into ecosystems. - **Level 2: Primary Consumers** – Herbivores such as deer, grasshoppers, and zooplankton ingest producers to access stored energy.

These organisms initiate nutrient transfer to higher tiers. - **Level 3: Secondary Consumers** – Carnivores that eat herbivores, like foxes or small fish, harness energy accumulated in plant-eating species. - **Level 4: Tertiary Consumers** – Apex predators such as wolves or eagles occupy this top tier, regulating population dynamics and maintaining ecological equilibrium.

Their presence signals a healthy, resilient food web. Each jump between levels sees dramatic energy loss—typically only 5% to 10% of energy is transferred, with the rest dissipated as heat, movement, or unused biomass. This inefficiency explains why food chains rarely exceed four or five levels and why large predators are far less common than their prey.

Trophic levels also illuminate ecosystem vulnerability. When a base species declines—due to climate shifts, pollution, or overharvesting—entire chains destabilize. For instance, coral reef degradation undermines primary producers, cascading upward to threaten fish, sharks, and human communities dependent on marine resources.

Interactions Beyond the Stacks: Complexity Within and Beyond Trophic Boundaries

Though trophic levels follow a linear model, real-world ecosystems are far more nuanced.Many species occupy multiple roles, blurring strict categorization. Omnivores—like bears or humans—consume plants and animals, straddling two or more levels. Scavengers such as vultures exploit dead matter across levels, connecting decomposers with higher consumers.

This flexibility enhances resilience, allowing ecosystems to adapt when resource flows fluctuate. Moreover, trophic cascades demonstrate how top-down regulation maintains balance. The legendary case of wolves in Yellowstone National Park exemplifies this: their reintroduction suppressed elk populations, enabling willow and aspen recovery, which in turn supported beaver colonies and songbird diversity.

“Trophic cascades are nature’s regulatory nervous system,” observed ecologist Robert Paine, “showing that apex predators shape landscapes from root to canopy.”

Trophic level classification is indispensable for conservation. By mapping species into functional strata, scientists identify keystone species—those whose removal triggers disproportionate ecosystem collapse. Protecting these linchpins preserves energy pathways and biodiversity alike.

Restoration ecologists use trophic data to rebuild degraded habitats, restarting energy flows where they had broken.

Applications in Science and Stewardship

Beyond theoretical ecology, trophic levels inform practical environmental work. In fisheries management, understanding trophic dynamics prevents overfishing by setting catch limits based on energy flow capacity. Similarly, agricultural systems use crop-livestock rotations that mimic natural trophic cycles, enhancing soil fertility and reducing chemical inputs.Hydrologists apply trophic analysis to wetlands, where algae and aquatic plants sustain insects, fish, and birds—forming critical links between water quality and wildlife productivity. Even in urban planning, green corridors aim to preserve trophic connectivity, allowing pollinators and small mammals to move freely through human-dominated landscapes. In climate science, trophic models predict how shifting temperatures or CO₂ levels disrupt food webs.

For example, warming oceans force zooplankton to migrate poleward, decoupling from fish larvae dependent on them—threatening fisheries and food security. By integrating trophic data into climate models, researchers forecast ripple effects across marine and terrestrial systems alike.

In every ecosystem, trophic levels compose an invisible yet indispensable scaffold—organizing life, governing flow, and exposing fragility.

From microscopic algae to majestic tigers, each tier fuels the next in a delicate, energy-driven dance. Recognizing and safeguarding these roles ensures ecosystems endure, supporting not only biodiversity but human wellbeing across generations.

Related Post

Ms Sethi Xxxxxx: Engineering the Future of Healthcare Through Innovation and Equity

Emily Wilson Bio Wiki Age Husband Odyssey Translation Books and Net Worth