What Is a Nucleophile? The Powerhouse Behind Chemical Reactions

What Is a Nucleophile? The Powerhouse Behind Chemical Reactions

Nucleophiles—literally “electron seekers”—are charged or electron-rich species central to countless chemical reactions, driving processes in organic synthesis, biochemistry, and materials science. Defined by their ability to donate a pair of electrons to a positively charged or electron-deficient atom, nucleophiles act as reactive agents in substitution and addition reactions. From the formation of life’s molecular backbone to industrial catalysis, their role is indispensable, making nucleophiles a cornerstone concept in understanding molecular behavior and design.

This article unpacks the chemistry behind nucleophiles, their types, reactivity patterns, and widespread influence across science.

At its core, a nucleophile is any species that donates an electron pair to form a new covalent bond. The term originates from “nucleo,” meaning nucleus, reflecting its affinity for positively charged centers like carbocations or transition metal complexes, though it extends far beyond acids. Unlike electrophiles—electron-pair acceptors—nucleophiles are rich in electron density, often stabilized by negative charge, lone pairs, or resonance.

This electron-providing nature makes them uniquely reactive in transformations where bond formation is key.

The Fundamental Chemistry of Nucleophilic Attack

Central to nucleophilic behavior is the concept of electron donation. When a nucleophile encounters an electron-deficient site—such as a carbon center bearing a partial or full positive charge—it engages in a directed attack, forming a new bond. This process is governed by several key principles:

- Electron Density > Electrophilicity: Nucleophiles thrive in environments where electron density draws them in; electron-withdrawing groups adjacent to a reactive center enhance nucleophilicity.

- Lone Pairs or Anionic Charge: Many nucleophiles carry a formal negative charge (e.g., hydroxide, cyanide), making lone electron pairs highly available for donation.

- Solvent Effects: Polar aprotic solvents stabilize nucleophiles by minimizing competition for their electron-rich sites, thus enhancing reactivity—critical in reaction design.

- Steric Accessibility: Bulky groups near reactive sites can hinder approach, influencing the reaction rate and selectivity.

These factors collectively determine nucleophilic strength, setting the stage for predictable behavior across diverse reaction contexts.

Classifying Nucleophiles: From Simple Anions to Complex Organometallics

Nucleophiles span a broad chemical landscape, categorized by charge, size, polarizability, and electronic character.

Broadly, they fall into two dominant classes: charged and neutral nucleophiles, each with distinct reactivity profiles.

Charged Nucleophiles: The Strong Attackers

Positive or negatively charged species dominate high-reactivity nucleophiles. Negatively charged nucleophiles such as hydroxide (OH⁻), cyanide (CN⁻), alkoxides (RO⁻), and Grignard reagents (RMgX) are among the most potent. For example:

- Hydroxide (OH⁻): Common in deprotonation and substitution reactions, though weaker in nonpolar solvents.

- Cyanide (CN⁻): Highly effective in nucleophilic acyl substitution due to strong back-donation into its antibonding orbital.

- Alkoxides (RO⁻): Facilitate esterification and ether formation through attack on carbonyl carbons.

Positively charged nucleophiles, such as methyl cation (CH₃⁺) in carbocation intermediates, react vigorously with nucleophiles like water or alcohols, driving SN1 reactions.

Their reactivity stems from inherent electron deficiency, though protonated forms typically lack nucleophilic character due to H⁺’s low charge density.

Neutral Nucleophiles: The Subtle but Strategic Players

Charge is not always required. Neutral nucleophiles, including ammonia (NH₃), water (H₂O), and pyridine, donate lone pairs without requiring a full negative charge. Despite their neutrality, their electron-rich nitrogen or oxygen atoms still direct attack in key reactions:

- Ammonia (NH₃): Reacts with alkyl halides via SN2 mechanisms, forming primary amines under phase-transfer catalysis.

- Water (H₂О): Acts as a nucleophile in hydrolysis, attack on carbonyl groups, and acid-base equilibrium.

- Pyridine and Other Aromatic Bases: Stabilize transition states through resonance in electrophilic aromatic substitution.

These neutral species underscore that nucleophilicity hinges less on charge and more on electronic structure and responsiveness.

Organonitrogen and Organometallic Nucleophiles: Precision in Synthesis

Specialized nucleophiles arise in advanced synthetic chemistry, particularly in organometallic and organonitrogen compounds.

These species combine metal centers or nitrogen lone pairs with organic moieties, enabling high selectivity and reactivity:

- Grignard Reagents (RMgX): Highly reactive carbon-containing nucleophiles used to form C–C bonds via addition to aldehydes and ketones, forming primary to secondary alcohols.

- Wagner-Meerwein Pontier reagents and Organolithium Compounds: Extend nucleophilic scope in complex carbocation rearrangements and protecting group strategies.

- Phosphines (PR₃) and Nitrosyl Complexes (NO): Provide subtle nucleophilic input in catalysis, particularly in transition metal-mediated reactions like cross-couplings.

Organometallics exemplify how nucleophiles can be engineered for specificity, making them indispensable in pharmaceutical development and fine chemical manufacturing.

Steric and Electronic Effects on Nucleophilic Performance

Beyond charge and identity, nucleophilicity is profoundly influenced by steric and electronic environments. Bulky substituents near reactive centers create steric congestion, slowing or redirecting attack—critical in asymmetric synthesis where selectivity determines product purity. Electron-donating groups (e.g., alkyl, –OCH₃) enhance nucleophilicity by increasing electron density on the nucleophile, while electron-withdrawing substituents (e.g., –NO₂, –CF₃) diminish it.

Take cyanide versus fluoride: fluorine’s strong electronegativity reduces its ability to donate electrons, making OH⁻ a far stronger nucleophile in polar aprotic solvents despite its neutral charge.

These nuances guide chemists in designing efficient synthetic pathways, predicting reaction outcomes, and troubleshooting low-yield transformations.

Real-World Applications: Nucleophiles Driving Innovation

Nucleophiles underpin transformative processes across disciplines. In pharmaceuticals, they construct the core frameworks of drugs—from penicillin’s β-lactam ring, formed by nucleophilic attack, to novel kinase inhibitors designed with tailored nucleophilic handles for enhanced binding. In industrial catalysis, nucleophilic reagents enable efficient C–N, C–O, and C–C bond formation, underpinning processes like pharmaceutical synthesis and polymer production.

In biochemistry, nucleophiles orchestrate enzymatic mechanisms: serine proteases rely on nucleophilic serine residues to cleave peptide bonds, demonstrating nature’s precision. Environmental chemistry also depends on nucleophiles—waste treatment systems utilize nucleophilic reduction (e.g., sulfate to sulfide) to detoxify industrial effluents, highlighting their dual role in innovation and sustainability.

The Nuance of Nucleophilicity in Solvent Environments

Solvent choice profoundly shapes nucleophilic behavior, affecting both reactivity and selectivity. Polar aprotic solvents—such as dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and acetonitrile—lack acidic protons, allowing nucleophiles to remain free and reactive.

These solvents stabilize charged transition states without coordinating too strongly to the nucleophile, enhancing attack speed. In contrast, polar protic solvents—water, alcohols, carboxylic acids—form hydrogen bonds with nucleophiles, solvating them and often reducing reactivity. For example, hydroxide ions in water move sluggishly due to extensive solvation, making early-phase reactions slower despite its strong nucleophilicity.

Mastery of solvent effects is thus critical in lab and scale-up chemistry, enabling precise control over reaction dynamics.

Predicting Reactivity: Trends and Theory Behind Nucleophilic Strength

Understanding nucleophilic strength requires historical insight and predictive frameworks. In the gas phase, nucleophilicity scales with charge and electron density: for anions, more negative charge equals stronger nucleophilicity. Ammonia (NH₃) outreacts hydroxide (OH⁻) in predicting reactions like methyl halide substitution because NH₃ better stabilizes the developing negative charge on the forming alkoxide–.

Across solutions, steric bulk shifts trends. ABNášek’s empirical trend highlights that bulkier anions, like thiolates (RS⁻), often behave as stronger nucleophiles than smaller OH⁻ in protic media—reluctant to engage bulky substrates but efficient where they can.

Modern quantum calculations further refine predictions, modeling transition states to estimate activation barriers and selectivity, bridging theory with experimental observation.

Through this layered understanding—chemical definition, classification, reactivity determinants, and real-world impact—nucleophiles emerge not merely as reactive ions, but as intelligent drivers of molecular transformation. Their strategic role in constructing complexity, enabling innovation, and sustaining biological and industrial systems cements their status as essential agents in chemistry’s most powerful reactions.

Related Post

Carrier Infinity Thermostat Reset From Frustration to Freedom in Minutes

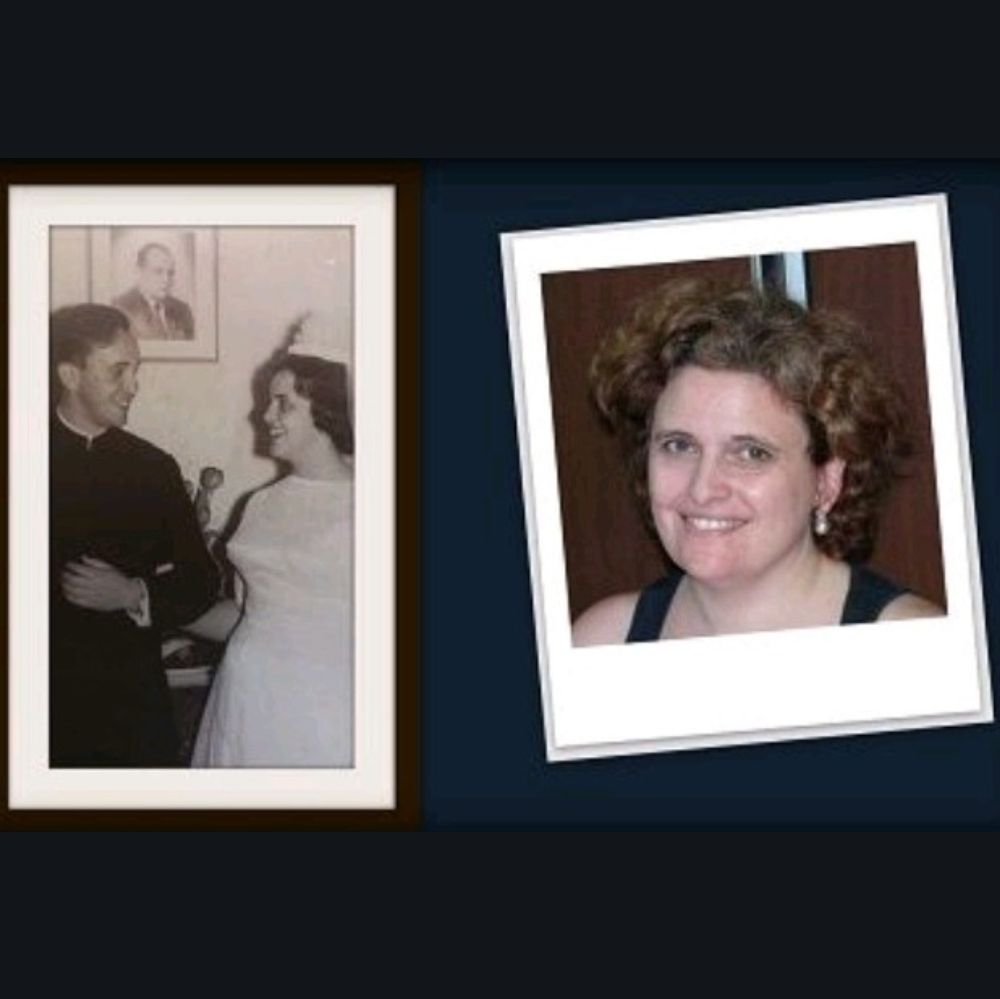

Marta Regina Bergoglio: The Quiet Architect Behind a Transformative Catholic Legacy