What Is a Community in Ecology? The Living Web That Shapes Our Planet

What Is a Community in Ecology? The Living Web That Shapes Our Planet

In ecology, a community refers to the intricate network of interacting plant and animal species coexisting within a defined geographic area, bound together by their shared habitat and ecological roles. Far from a passive collection, these biological assemblages reflect dynamic relationships—competition, predation, mutualism, and symbiosis—shaping ecosystem resilience and function. A community is not merely the sum of its species; it is a living, evolving system defined by energy flow, nutrient cycling, and complex interdependencies.

Understanding communities reveals how life thrives not in isolation but through interconnection. Understanding the Core: Defining a Community in Ecological Terms At its foundation, an ecological community comprises all species inhabiting the same physical space during the same time frame. This includes plants, fungi, animals, and microorganisms, each contributing to the community’s structure and stability.

Unlike populations—groups of one species—communities reflect biodiversity and interaction. For example, a coral reef community spans thousands of species: corals, fish, crustaceans, algae, and bacteria, each fulfilling unique roles that sustain the ecosystem. As ecologist Eric Pianka emphasized, “A community is the sum total of species interactions, not just their individual presence.” Components That Define a Community Communities are shaped by three essential components: structure, function, and dynamics.

**Structure** describes the physical arrangement and diversity of species. This involves species richness—the total number of species—and species evenness, which reflects how evenly individual populations contribute to the community. A mature forest, with layered canopy, understory, and ground vegetation, exemplifies structural complexity.

Different niches—spatial, temporal, or behavioral—enable species coexistence. **Function** highlights ecological roles species play. These include producers (photosynthetic organisms), consumers (herbivores, carnivores, omnivores), and decomposers (fungi and bacteria).

Producers convert solar energy into biomass, fueling food webs. Top predators regulate prey populations, preventing ecosystem collapse. Decomposers recycle nutrients, closing the loop of matter.

**Dynamics** involve change over time through processes such as succession, disturbance, and adaptation. Communities evolve after events like wildfires, floods, or volcanic eruptions—a process known as ecological succession. Pioneer species colonize barren ground, slowly paving the way for more complex communities.

Human activity and climate change now accelerate these dynamics, altering long-established balances. Types of Ecological Communities: From Forests to Reefs Ecologists identify distinct community types based on environmental conditions and dominant life forms. - **Terrestrial Communities**: Dominant in forests, grasslands, and deserts, these communities are driven by plant productivity and soil fertility.

Temperate forests feature layered associations—canopy trees, shade-tolerant shrubs, and ground flora—each supporting specialized fauna. Tropical rainforests rival grasslands in species richness, hosting intricate mutualisms like pollination and seed dispersal. - **Aquatic Communities**: Found in freshwater (lakes, rivers) and marine (oceans, estuaries) environments.

Coral reefs represent vibrant aquatic hubs, where symbiotic algae sustain reef builders and support thousands of fish species. Riverine communities depend on water flow and sediment, influencing fish migration and invertebrate distribution. - **Extreme Environments**: Harsh conditions yield unique communities.

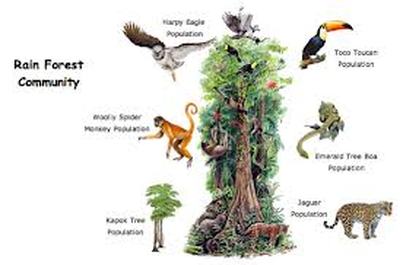

Hydrothermal vents host chemosynthetic bacteria sustaining tube worms, clams, and shrimp in complete darkness. Polar communities adapt to extreme cold, with species like penguins, seals, and Antarctic krill evolving specialized thermoregulation and foraging strategies. Case Study: The Rainforest Community The Amazon rainforest offers a vivid illustration of ecological community dynamics.

Here, towering trees form a multi-strata canopy: emergent layer above, dense mid-canopy, and dense understory. Each layer hosts species adapted to light availability, humidity, and predation pressure. Hummingbirds pollinate specialized flowers while feeding on nectar, and leafcutter ants cultivate fungal gardens—demonstrating mutualism.

Disruption of this web, whether by deforestation or climate shifts, risks cascading collapse. Interactions Within Communities: Networks of Life The strength of any ecological community lies in its network of biotic interactions. - **Competition** drives species to partition resources—differing feeding times, microhabitats, or dietary preferences—to minimize resource clashes.

For example, African savanna herbivores like zebras and wildebeests eat different grass heights, reducing direct competition. - **Predation and Herbivory** regulate population sizes, preventing unchecked growth of single species. Apex predators such as wolves in Yellowstone control deer numbers, indirectly promoting plant recovery and enhancing biodiversity—a phenomenon known as a trophic cascade.

- **Mutualism** reinforces stability. Bees pollinate flowers while gathering nectar; root-fungi partnerships (mycorrhizae) extend plant nutrient absorption. These cooperative relationships exemplify interdependence, where survival depends on partnership.

- **Decomposition and Nutrient Cycling** sustain community function. Detritivores break down dead matter, returning nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon to the soil. Fungi and bacteria convert organic material into usable nutrients, closing critical biogeochemical loops.

Human Impact and Conservation Implications Modern communities face unprecedented pressure. Habitat fragmentation, pollution, invasive species, and climate change disrupt long-established ecological balances. The Coral Reef Community, for instance, suffers bleaching events when ocean temperatures rise, destabilizing entire reef systems.

Similarly, deforestation fragments forest communities, isolating species and reducing genetic exchange and resilience. Yet, this understanding powers conservation. Restoring native species, recreating habitat corridors, and managing invasive threats rebuild community integrity.

Rewilding projects reintroduce keystone species—like wolves in Yellowstone—reviving trophic dynamics. Protecting biodiversity at the community level ensures ecosystem services—clean water, pollination, and carbon storage—continue to support human well-being. As ecologist E.O.

Wilson noted, “From the tiniest insect to the tallest tree, every species is a thread—unravel one, and the tapestry frays.” A community in ecology is far more than a label; it is the living framework through which nature operates, adapts, and endures. Recognizing, preserving, and restoring these dynamic assemblages is essential for sustaining planetary health and human survival. The concept of a community in ecology reveals a world of complexity, resilience, and interconnection—one that demands not only scientific understanding but active stewardship.

Related Post

2024 Toyota Yaris Hybrid: Precision Engineering in Compact Form – Length & Dimensions Revealed

The Ultimate Guide to Grand Theft Auto V’s Xbox 360 Cheat Codes: Unlock Unlimited Freedom

The Digital Chameleon: How Andy Serkis Revolutionized Performance Capture and Redefined Modern Acting