What Does True Breeding Mean? Unlocking the Secrets of Genetic Consistency

What Does True Breeding Mean? Unlocking the Secrets of Genetic Consistency

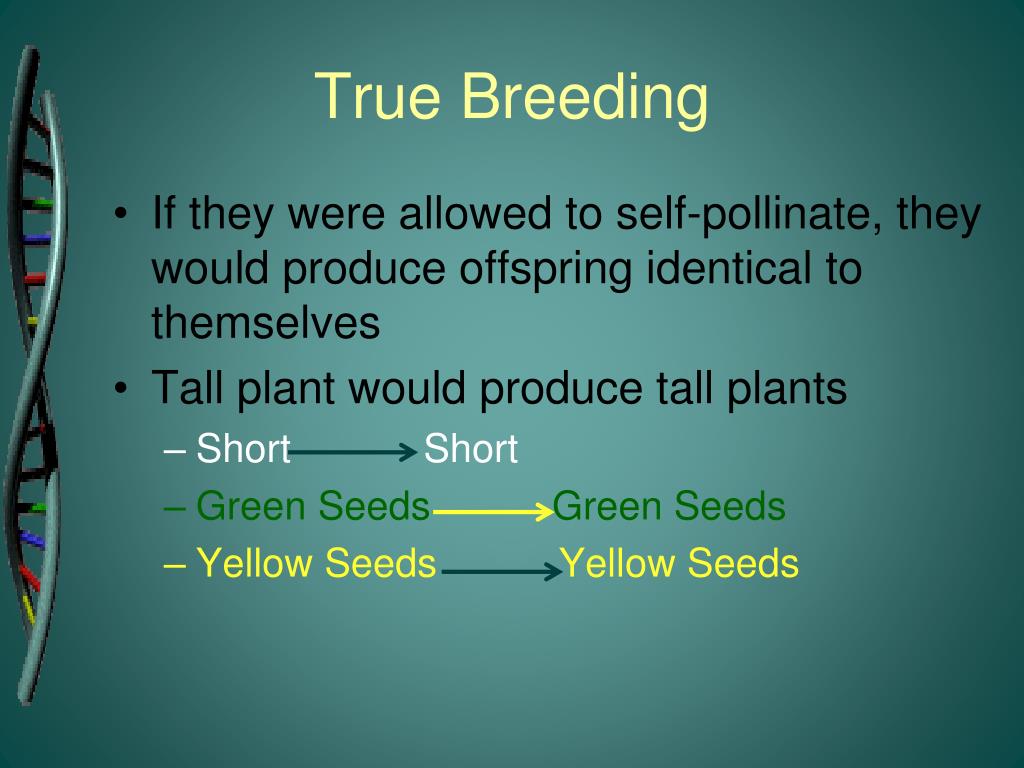

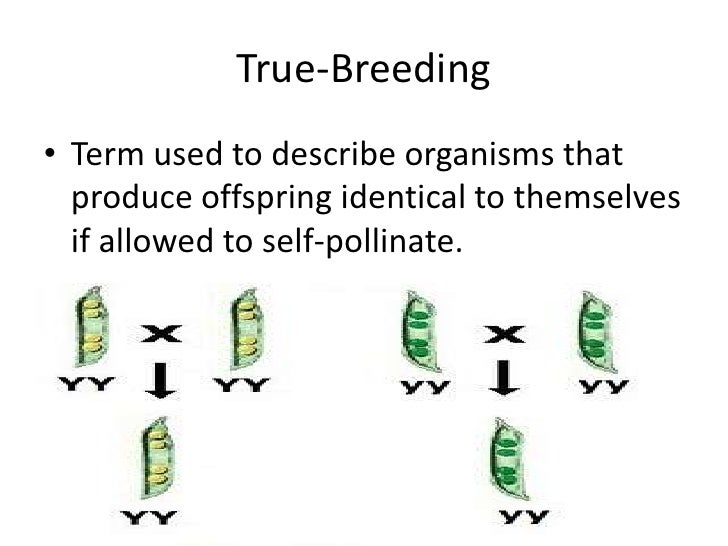

True breeding refers to the consistent transmission of specific inherited traits across generations, a phenomenon that lies at the heart of classical genetics. When organisms are truly bred true, every offspring exhibits the same genetic characteristics as its parents—showing predictable, stable phenotypes without variation. This principle, rooted in Mendelian inheritance, reveals how genes are passed down in a predictable, reliable pattern, forming the foundation for plant and animal breeding, scientific research, and even forensic genetics.

According to geneticist Alcide d’Orbigny, “True breeding is the expression of genetic uniformity, where an organism’s genotype produces a single, unaltered phenotype across multiples generations.” At its core, true breeding depends on homozygosity—the condition where an organism carries two identical alleles for a particular gene. In such cases, dominant or recessive traits are expressed consistently, eliminating heterozygosity that causes variation. For example, a pea plant variant bred true for tall stature will produce only tall offspring, provided it remains homozygous for the height gene.

Conversely, a heterozygous plant may show variable height, blending traits or skipping generations entirely.

The Science Behind Genetic Uniformity

True breeding emerges from generations of selective mating among individuals that consistently pass identical alleles. Over time, this practice stabilizes gene frequencies, reducing genetic diversity within a line.Key factors influencing true breeding include: - **Homozygosity**: The cornerstone of true breeding ensures offspring inherit identical copies of a gene, reinforcing trait consistency. - **Mendelian Segregation**: While Mendel showed traits separate evenly in G1 generations, true breeding occurs only in subsequent generations (G2 and beyond) when linked genes are fixed. - **Environmental Stability**: Genotypic expression aligns closely with phenotype when environmental conditions—temperature, soil, light—are controlled, minimizing external noise in trait outcomes.

Scientists rely on true breeding to establish genetic reference lines. In agricultural research, durable true-breeding strains of crops like maize or rice assure policymakers and breeders that traits such as drought tolerance or disease resistance are heritable and reproducible.

Applications in Modern Agriculture and Breeding

True breeding is the backbone of sustainable crop and livestock improvement.Plant breeders use homozygous lines to develop uniform, high-yielding varieties. For example, the development of hybrid corn hinges on two true-breeding parent lines—brilled for optimal productivity and resilience—whose combination produces offspring with superior performance. This strategy avoids the “genetic confusion” of heterozygosity, ensuring consistent quality across every harvest.

In animal husbandry, true breeding guarantees predictable meat quality, milk composition, or wool characteristics. The Holstein cattle, prized for high milk output, trace their uniformity to strict true-breeding protocols that preserve desirable alleles over generations. However, reliance on true breeding comes with trade-offs: reduced genetic diversity can heighten vulnerability to pests and shifting climates.

Modern breeding programs now integrate true breeding with molecular tools—such as marker-assisted selection—to balance uniformity with adaptive genetic variation.

Case Studies: Successes and Challenges

Historical examples underscore true breeding’s transformative power. The green revolution in the mid-20th century hinged on true-breeding wheat varieties developed by Norman Borlaug.These lines, fixed for disease resistance and high grain yield, enabled rapid leaps in food production across South Asia and Latin America, saving millions from famine. Yet, true breeding’s limitations are evident in the Irish Potato Famine. Widespread cultivation of a single true-breeding potato variety—Lumper—left Irish agriculture genetically uniform and disaster-prone.

When Phytophthora infestans struck, the lack of genetic diversity allowed the fungus to devastate 70% of potato crops, exposing a critical vulnerability. Today’s scientists mitigate such risks through controlled crossbreeding, preserving core true breeding for foundation traits while introducing diversity via outcrossing. This hybrid strategy ensures fixed performance without sacrificing long-term adaptability.

Genetic Integrity and Ethical Considerations

The pursuit of true breeding demands rigorous genetic standards and ethical vigilance. Maintaining homozygosity often requires generations of careful selection, parfois involving clonal propagation or genomic editing technologies. While these tools accelerate progress, they raise questions about long-term ecological impacts and genetic equity.In conservation, true breeding programs restore endangered species by preserving pure lineages—such as in captive breeding for black-footed ferrets or California condors—yet biologists caution against over-reliance on genetic uniformity at the cost of natural variation. True breeding, when applied wisely, advances human goals but must remain guided by ecological and ethical awareness.

True breeding represents a precise, powerful genetic strategy—one that stabilizes desirable traits across generations but demands thoughtful balance between uniformity and diversity.

From feeding nations to protecting endangered species, its principles underpinning modern genetics remain indispensable, offering both promise and caution in equal measure.

Related Post

Allenwood Low Correctional Facility: A Harrowing Journey of Survival and Resilience Against All Odds

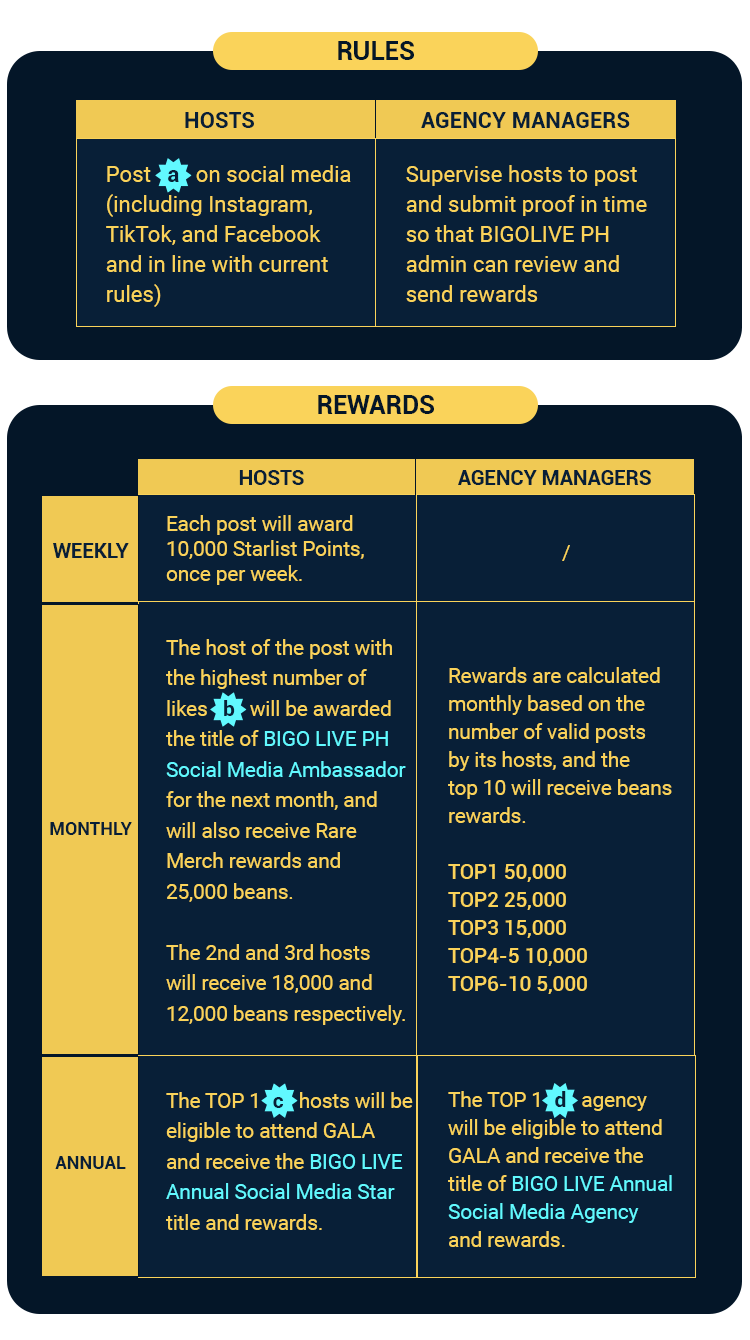

What Is Bigo Live And How Does It Work? The Next Frontier of Interactive Game Streaming

List and Facts You Should Know

Electric Carts For Handicapped: Revolutionizing Independence on Wheels