Violating the Octet Rule? When Atoms Break Octets—and Why It Still Works

Violating the Octet Rule? When Atoms Break Octets—and Why It Still Works

In the atomic world, stability is often dictated by a rule as foundational as it is flexible: the octet rule. For most main-group elements, this principle holds steadfast—atoms strive to attain eight valence electrons, mirroring the electron configuration of noble gases. Yet, exceptions to this rule reveal the dynamic nature of chemical bonding, challenging rigid rules while underscoring chemistry’s deeper logic.

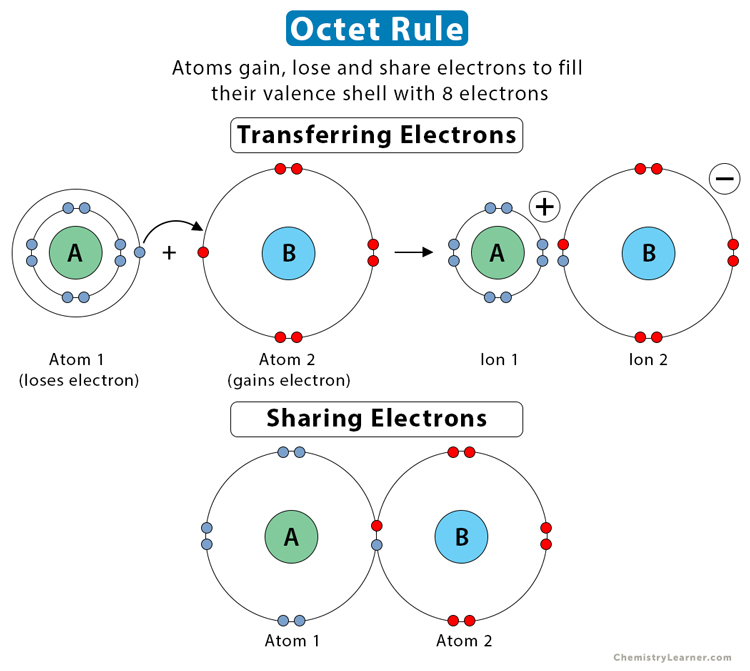

The octet rule—that atoms gain, lose, or share electrons to achieve eight electrons in their outermost shell—has long guided predictions in molecular structure. But when exceptions emerge, they expose the nuanced interplay of electron configurations, energy landscapes, and elemental identity.

While carbon confidently completes its octet with four bonds—shaping organic complexity—other elements defy this template.

Some atoms never form eight electrons, others do so only under specific conditions, and in rare cases, entire classes of molecules stray from the pattern entirely. Understanding these deviations is not merely an academic exercise; it deepens insight into reactivity, bond types, and material behavior. From chaotic radical species to expanded-valent transition metals, the exceptions to the octet rule offer a compelling window into chemistry’s true complexity.

The Fundamentals: When and Why the Octet Rule Applies

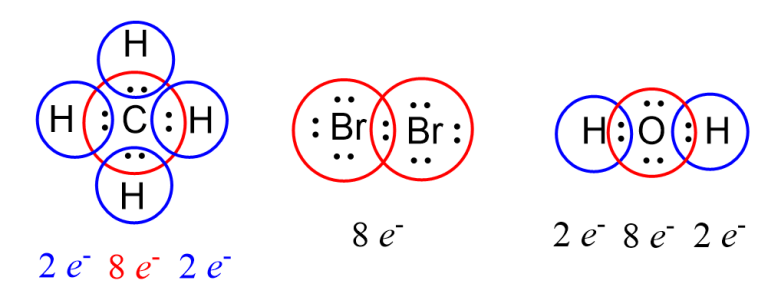

The octet rule emerged from empirical observation, codifying how elements from lithium to neon arrange their valence electrons.Atoms with fewer than eight valence electrons typically gain, lose, or share electrons to mimic noble gas stability. Hydrogen and helium, limited to two electrons, achieve stability broadly through duet configurations. For main-group elements, especially in periods two and three, this translates into predictable bonding: carbon completes its octet via four single bonds in methane, while oxygen achieves stability in water through two double bonds and two lone pairs.

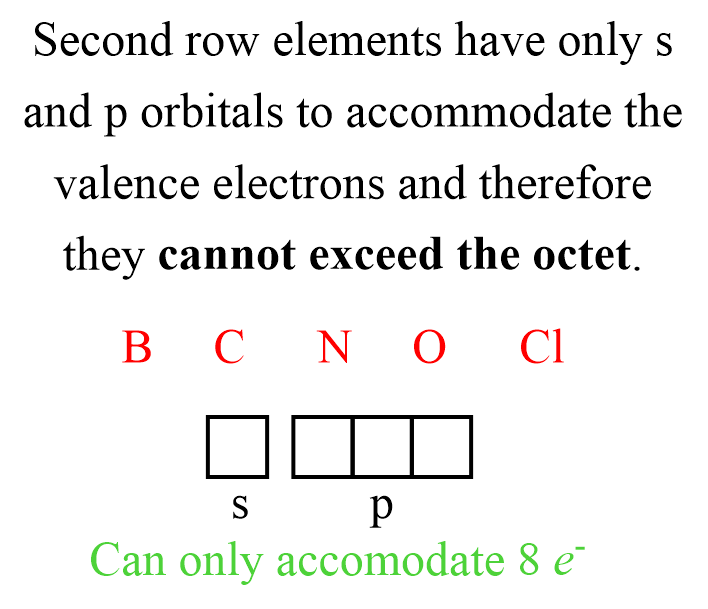

Yet the rule’s universality fades as atomic size, electronegativity, and orbital availability reshape bonding possibilities. Periodic trends reveal that lighter elements obey the octet strictly, but heavier elements—particularly in the third period and beyond—display increasing tolerance for more or fewer electrons, leading to structured exceptions that redefine bonding logic.

Elements Outside the Box: Common Non-Octet Behaviors

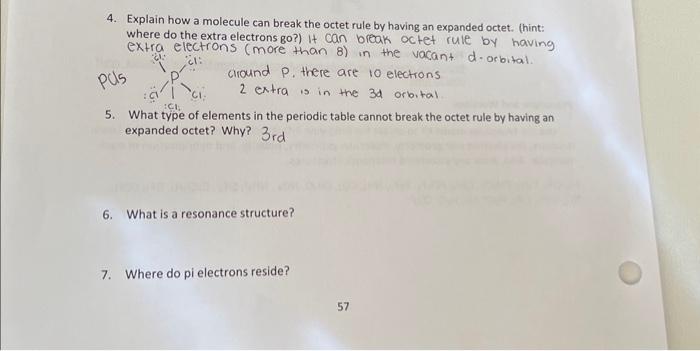

Many main-group elements defy the octet rule, especially those capable of expanding their valence shell beyond eight.Elements like phosphorus, sulfur, and chlorine routinely form five-, six-, and seven-electron species. Phosphorus pentachloride (PCl₅), for example, gains importance in industrial chemistry not despite violating the octet, but because phosphorus stabilizes a five-coordinate structure through d-orbitals, enabling compounds with unique reactivity. silicon, though in the same period as carbon, easily exceeds octet participation, forming stable compounds like silicon tetrachloride (SiCl₄) and complex silicates.

Unlike carbon’s subtle octet fulfillment, silicon’s expanded octet stems from its larger atomic radius and lower ionization energy compared to carbon, enabling greater orbital flexibility. Similarly, sulfur forms stable seven-electron species such as SF₆ and expanded-octet molecules like S₄Cl₆, where sulfur utilizes d-orbitals to support tetravalent environments that contradict simple electron counting. “The octet is a useful ideal, not a universal law,” notes chemist Dr.

Elena Marquez. “Elements with accessible d-orbitals—especially in third-row species—redefine how electron sharing shapes molecular stability and reactivity.”

Radical Species and Unpaired Electrons: Chemistry in Flux

Radicals—species with unpaired electrons—are among the most striking exceptions to the octet rule. Methylidene (CH₂) and chlorine radicals (Cl·) persist in energy landscapes due to radical stability driven by resonance and hyperconjugation, even as their valences break the eight-electron mold.Chlorine, though typically octet-fulfilling in molecules, exists as a reactive radical in atmospheric chemistry and combustion, where unpaired electrons fuel redox cascades. “Radicals aren’t chaos—they’re chemistry in motion,” says Dr. James Lin, a physical chemist specializing in oxidative processes.

“Their transient existence reveals fundamental principles about electron delocalization and energy barriers that stable octet-bound molecules obscure.” These species defy octet logic but remain critical to atmospheric transformations, polymerization, and biological signaling—underscoring that stability isn’t the sole driver of chemical behavior.

Expanded Valence and d-Orbital Utilization in Transition Elements

While main-group chemistry expands the octet concept via d-orbital participation, transition metals introduce an even deeper departure. Elements like chromium and copper exhibit irregular electron configurations—such as [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹ instead of the expected [Ar] 3d⁴ 4s²—optimizing crystal field stabilization energy (CFSE) and enabling expanded valence.Chromium in its core oxidation state, Cr⁰, possesses a half-filled 3d⁵ configuration, enhancing magnetic and catalytic properties. Copper, with [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s¹, not only stabilizes a 10-electron valence shell but also forms compounds like Cu₂O and Cu⁺ ions with atypical coordination geometries. These metals routinely achieve more than eight electrons in their valence shells, relying on hybridized d-s strength to support complex, high-coordination structures that defy conventional bonding models.

Exceptions in Coordination Chemistry: Complex Molecules Beyond Octet Limits

In coordination complexes, ligands coordinate to a central metal ion via electron donation, often distorting classical octet expectations. Iron in hemoglobin, for instance, stabilizes a six-coordinate octahedral geometry in deoxyhemoglobin yet participates in transient four-coordinate lithium complexes in phase-transfer catalysts. Such variations arise not from octet violation per se, but from ligand-field effects that modulate electron availability and orbital occupancy.“The octet is a local measure,” explains Dr. Priya Desai, coordination chemistry expert. “At the molecular scale, metal-ligand interactions redefine stability, allowing expanded or strained valence shells without chemic instability.” These systems demonstrate that chemical bonding’s adaptability ensures functionality beyond rigid electron counts—an insight central to fields from catalysis to materials science.

The Broader Implication: Science Beyond Stability

The exceptions to the octet rule are more than curiosities; they are gateways to understanding chemical robust

Related Post

Emmy Rossum Angelyne Bio Wiki Age Husband and Net Worth

Chelsea Northrup Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Husband