Vertical Integration in U.S. History: How Control of the Supply Chain Shaped Industry and Economy

Vertical Integration in U.S. History: How Control of the Supply Chain Shaped Industry and Economy

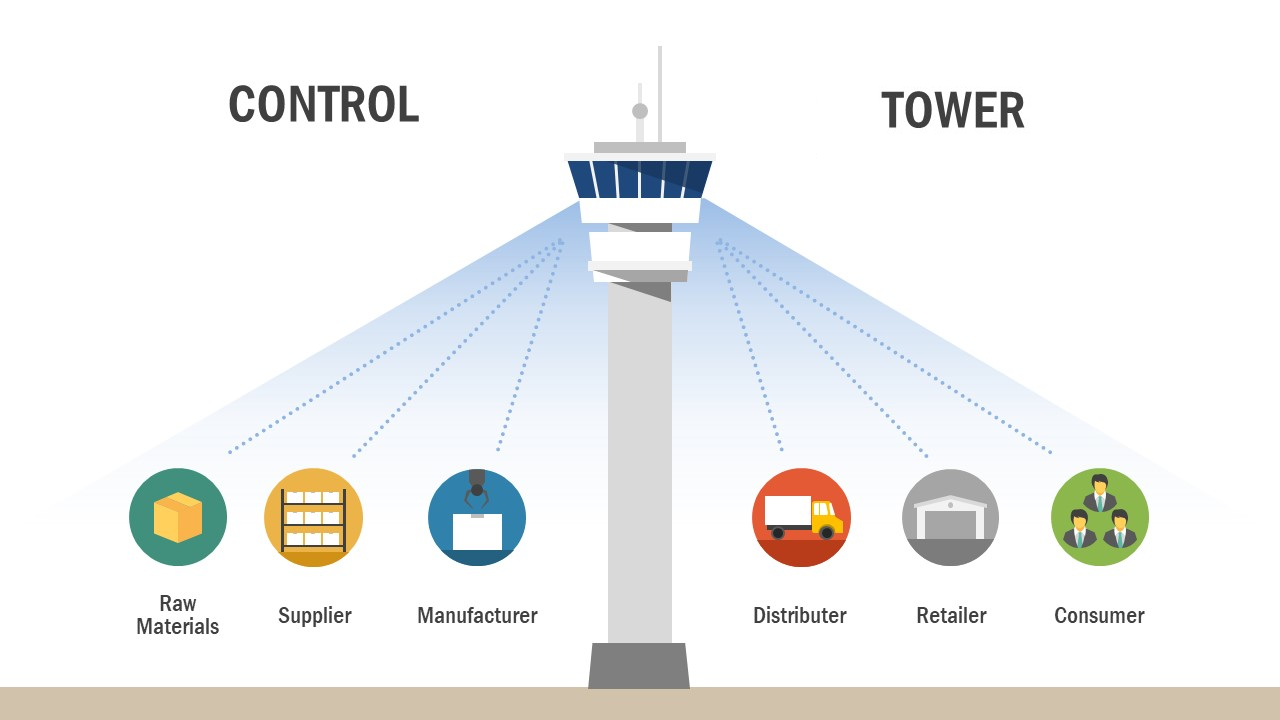

In the relentless march of American industrialization, vertical integration emerged as a transformative strategy—where companies extended control from raw materials to final production and distribution. This defining business model, defined as the consolidation of multiple stages of a production supply chain under a single corporate umbrella, reshaped industries from steel to oil, redefined competition, and influenced government policy for over a century. Rooted in necessity and ambition, vertical integration illustrates a pivotal chapter in U.S.

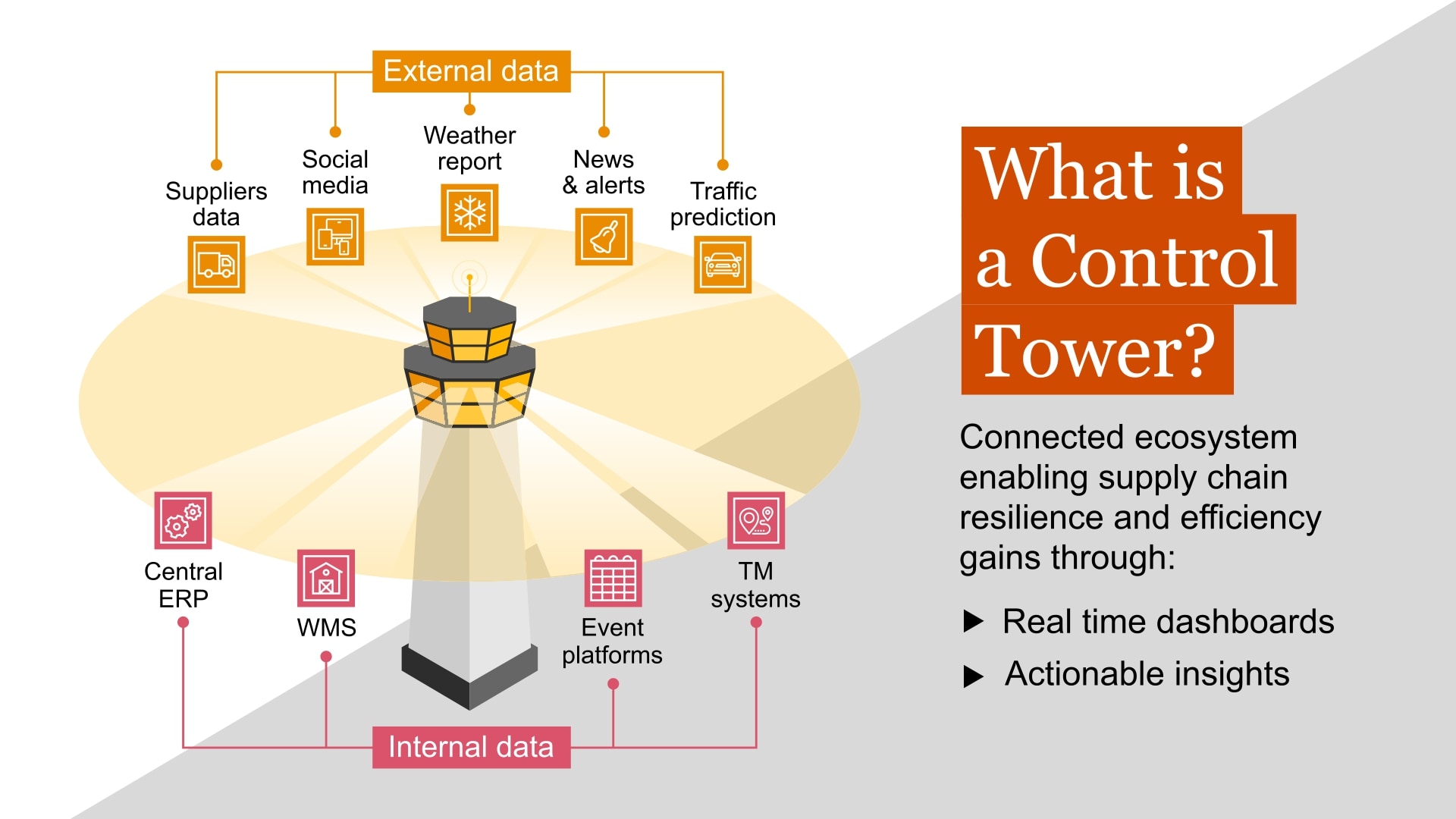

economic history, where efficiency, market dominance, and innovation collided. Vertical integration thrives on structure—companies that own or tightly manage suppliers, manufacturers, logistics, and retailers reduce dependency, cut costs, and accelerate decision-making. Historically, this approach allowed industrial titans to stabilize operations amid volatile markets and supply chain disruptions.

As economist Alfred Marshall noted, “The advantage of vertical control is not merely in cost reduction, but in synchronizing every stage of production.” Indeed, during the Gilded Age, firms like Carnegie Steel mastered this coordination, squeezing margins while ensuring consistent output.

The Birth of Vertical Integration in America’s Industrial Expansion

The roots of vertical integration stretch deep into the 19th century, as America transitioned from regional economies to national industrial powerhouses. Railroads, for example, were among the earliest adopters—building not just tracks but integrated fleets of locomotives, coal mines, and maintenance facilities under unified management.This vertical control enabled faster delivery times, lower fares, and safer freight transport, fueling westward expansion and commerce. Key industrial sectors embraced vertical integration as a competitive weapon. Consider John D.

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which by the 1880s controlled not only oil drilling but refining, pipelines, tankers, and even barrel manufacturing. By owning each step, Rockefeller eliminated inefficiencies and undercut rivals. “It is not competition that kills,” Rockefeller famously observed, “but disorganized competition.” His method became a blueprint for modern conglomerates.

Notable Early Examples Several landmark cases define vertical integration’s rise: - **Standard Oil (1860s–1911) controlled upstream drilling and drilling equipment, midstream pipelines and refineries, and downstream distribution—including retail outlets. - **U.S. Steel (1901) merged mines, coal suppliers, iron ore producers, and steel mills to dominate national steel output.

- **Ford Motor Company (1910s) vertically integrated by acquiring rubber plantations in Brazil and glass manufacturers, aiming to control every input for the Model T assembly line. These corporations didn’t simply expand—they redefined efficiency. Ford’s River Rouge Plant, completed in 1928, epitomized industrial ambition: steel was turned into rails, tires, and engines on a single site, reducing reliance on external suppliers and minimizing waste.

Economic and Competitive Advantages The power of vertical integration lies in its multifaceted benefits. Economies of scale enabled cost reductions—by managing procurement, production, and logistics centrally, firms reduced per-unit expenses. Control over supply chains also shielded companies from external shocks: shortages of raw materials or supplier delays became less critical.

Beyond efficiency, innovation accelerated. With full visibility into the production chain, companies could identify bottlenecks and streamline processes. For instance, Ford’s control over rubber supply allowed faster innovation in tire design and durability—key to Model T success.

Moreover, vertical integration strengthened market power: dominant players could set prices, influence distribution, and deter new entrants through resource control. Yet this dominance was not without friction. Vertical integration often blurred competitive boundaries, inviting antitrust scrutiny.

The 1911 Supreme Court ruling that broken Standard Oil was an illegal monopoly underscored growing concerns about concentrated power. Regulators debated whether vertical integration was a tool for progress or a path to monopolistic dominance. Still, its economic logic endured—many industries adopted hybrid models to retain control without full ownership.

Shift Toward Horizontal and Conglomerate Models By the mid-20th century, vertical integration faced new challenges. Regulatory reforms tightened antitrust enforcement, and managerial complexities grew with expanding operations. Firms began favoring horizontal integration—merging with peers in the same sector—or diversification into unrelated businesses.

Yet vertical strategies persisted where control over inputs remained strategic—pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and energy sectors retained integrated supply chains to safeguard innovation and supply security. Modern Echoes in U.S. Industry Today, vertical integration remains a vital strategy.

Tesla controls battery production through Gigafactories while managing raw material sourcing, a modern echo of Ford’s ambitions. Apple integrates chip design, software development, and retail—balancing vertical depth with digital integration. In agriculture, companies contract directly with farmers to standardize inputs and ensure quality, mirroring historical practices but with data-driven precision.

Vertical integration’s legacy is embedded in the American economic fabric. It spurred industrial might, accelerated technological advancement, and provoked enduring debates about market fairness. As industries evolve, control of the chain from corner stone to consumer remains a powerful lever—testament to a historical strategy centuries in the making.

Vertical integration in U.S. history is more than a business tactic—it is a lens through which to view America’s transformation from fragmented economy to industrial behemoth. Its story weaves efficiency with power, innovation with monopoly, and ambition with regulation.

In shaping the rise of modern industry, vertical integration stands as a defining force—structurallyintegrating not just supply chains, but the very contours of American economic power.

Related Post

Uncover The Truth: Was Britney Griner Assigned Male or Female at Birth?

Super Mario Bros. Movie: Cast & Giuseppe's Role Unveiled

Why Justin Bieber’s Lyrics Resonate Like Holy Scriptures in Modern Pop

Understanding Alexander B. Greenspan: Architect of Modern Financial Thought