Vacuoles: The Silent Powerhouses Inside Eukaryotic Cells — Why Prokaryotes Lack Them and What It Means for Cellular Evolution

Vacuoles: The Silent Powerhouses Inside Eukaryotic Cells — Why Prokaryotes Lack Them and What It Means for Cellular Evolution

Vacuoles stand as one of the most distinctive and functionally vital organelles in eukaryotic cells, enabling efficient storage, compartmentalization, and dynamic regulation of cellular substances. Unlike prokaryotic cells, which lack true vacuoles, eukaryotes harness these membrane-bound sacs to orchestrate complex physiological processes. This profound difference underscores a key evolutionary divergence between cellular domains, revealing how structural innovations shape biological capability.

Understanding why vacuoles exist only in eukaryotes — and never in prokaryotes — illuminates fundamental principles of cellular organization, adaptation, and complexity.

The Structural and Functional Significance of Eukaryotic Vacuoles

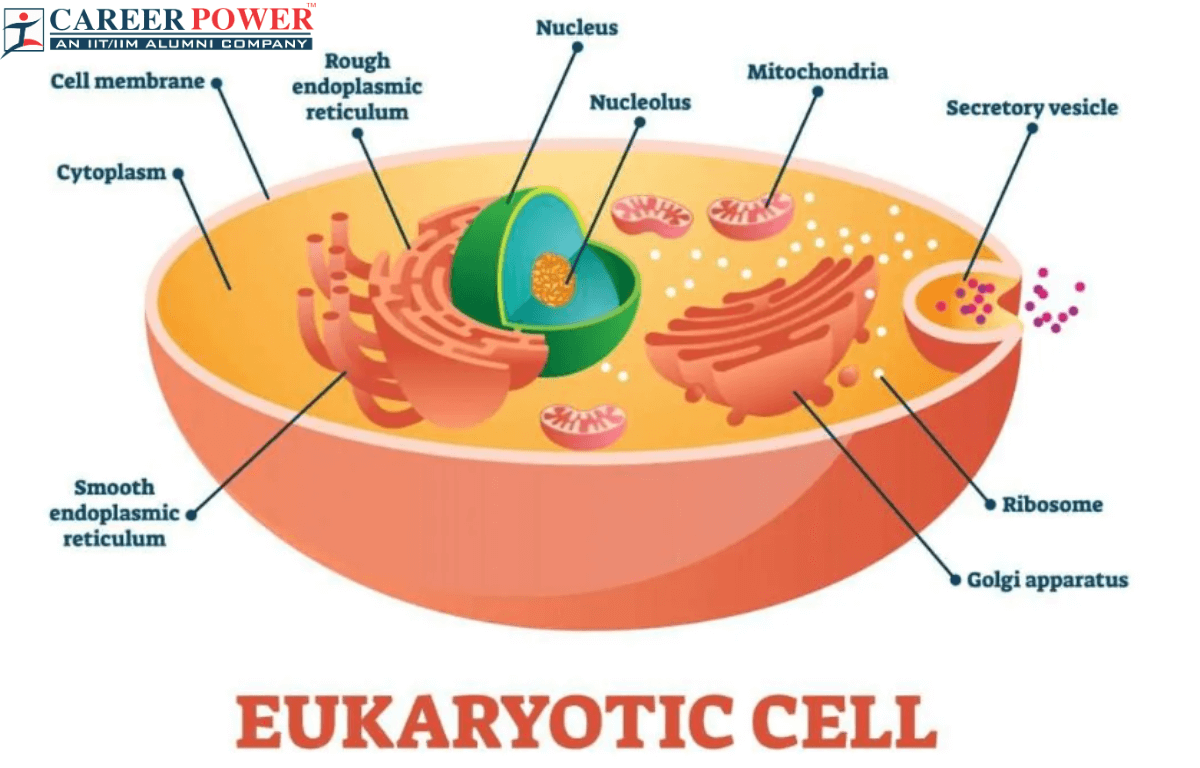

Eukaryotic vacuoles are bounded by a single lipid bilayer, creating discrete internal compartments that serve multiple roles. These organelles are far more than passive storage units; they actively participate in sorting, detoxifying, and recycling cellular materials. The central feature is their membrane, which maintains an internal environment distinct from the cytosol, allowing for precise control of pH, ion concentration, and metabolic reactions.In light and plant cells, large central vacuoles occupy up to 90% of cell volume, enabling efficient water uptake and turgor pressure generation essential for structural support—especially critical in non-vascular plants. Key Functions Include: - **Storage:** Vacuoles sequester ions, nutrients, plastic pigments (e.g., chlorophyll in plant vacuoles), and waste products, preventing interference with cytosolic processes. - **Waste Management:** Lysosomal-type vacuoles engulf and degrade cellular debris, breakdown of damaged organelles, and foreign invaders.

- **Osmoregulation & Turgor Pressure:** By regulating water influx through osmosis, vacuoles maintain cellular integrity and enable plant cells to stand rigidly without external support. - **Metabolic Hub:** Some vacuoles house enzymes for hydrolysis and metabolic intermediates, acting as biochemical reactors within the cell. As biologist Nancy Moran observes, “The evolution of vacuoles represents a quantum leap in intracellular compartmentalization, allowing eukaryotes to refine biochemical control with unprecedented precision.” This capability enables eukaryotic cells to handle increased complexity, from cellular signaling cascades to specialized defense mechanisms.

Vacuoles vary in size, number, and specialization across cell types. Animal cells typically contain a few small vacuoles involved in endocytosis and transient storage, while yeast and plant cells feature one or more large central vacuoles acting as cellular vaults. Their dynamic membrane fusion and fission events support constant remodeling in response to environmental cues.

Vacuoles in Eukaryotes vs.

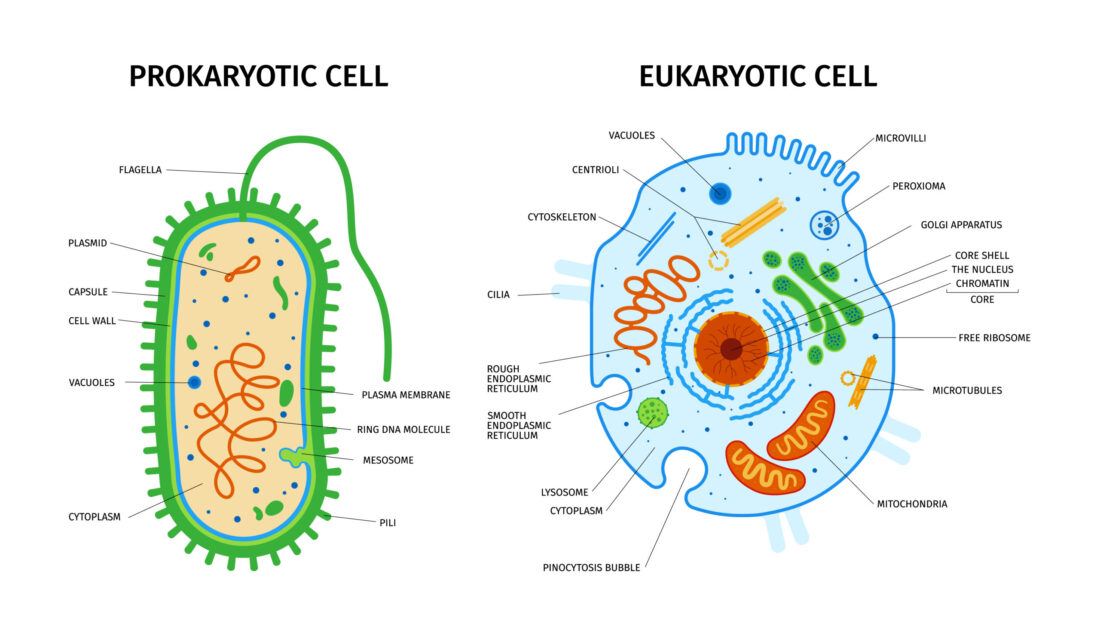

Prokaryotes: A Fundamental Cellular Divide Prokaryotic cells—encompassing bacteria and archaea—lack vacuoles entirely, relying instead on simpler membrane-bound microcompartments or folding of the cell membrane for selective transport. Though prokaryotes possess transport proteins, vesicle-like vesicles, and occasional inclusion bodies, these structures lack the membrane-confined, organelle-level functionality of true eukaryotic vacuoles. Structural Differences:** - Prokaryotic membranes surround localized storage granules and inclusion bodies but never form enclosed, autonomous organelles with a bilayer separating internal contents from the cytoplasm.

- Membrane-bound vacuoles in eukaryotes are genetically encoded, replicated during cell division, and capable of complex biogenesis via vesicular trafficking—processes absent in prokaryotes. - Prokaryotes rely on cytosolic enzymes, membrane transporters, and specialized inclusions (e.g., cyanobacterial gas vesicles) but none function like eukaryotic vacuoles in compartmentalizing entire metabolic pathways. Functional Limitations in Prokaryotes: - Lack of dedicated storage organelles restricts dynamic regulation of metabolites and waste.

- Limited osmotic control restricts growth in variable environments; turgor pressure regulation is minimal. - Waste accumulation occurs without dedicated degradation compartments, potentially slowing cellular replication and increasing susceptibility to toxins. “This absence isn’t merely anatomical—it’s evolutionary,” explains cell biologist Christopher Bley.

“Vacuoles emerged in the eukaryotic domain as internal spaces allowed for spatial separation of incompatible reactions and enhanced regulatory control—tools absent in simpler prokaryotic life.” Without vacuoles, prokaryotic cells remain constrained to relatively homogeneous internal conditions, favoring survival in stable niches rather than dynamic adaptation.

The evolutionary emergence of vacuoles closely follows other hallmarks of eukaryotic complexity: membrane-bound organelles, cytoskeletal networks, and endomembrane systems. Their development likely supported the rise of larger, more metabolically advanced cells capable of multicellularity.

Comparing eukaryotic vacuoles to prokaryotic membrane specializations reveals not just a structural difference, but a profound leap in cellular autonomy and functional sophistication.

Biological Implications: How Vacuoles Shape Eukaryotic Adaptability

Vacuoles are central to eukaryotic cells’ ability to thrive in diverse ecosystems—from soil bacteria growing in fluctuating moisture to complex multicellular organisms regulating internal chemistry across tissues. Their role in waste degradation supports cellular longevity and detoxification, reducing reliance on external removal. Turgor-driven growth underpins plant morphology and resilience against physical stress.In yeast, mutants lacking vacuolar function show reduced acid tolerance and impaired autophagy, demonstrating vacuoles’ indispensable role in survival under environmental duress. Animal cells, though less dependent on large vacuoles, use smaller domains for targeted signaling and recycling, enabling rapid responses to physiological demands. Beyond individual cells, vacuoles contribute to broad ecological and industrial relevance.

Plant vacuoles stabilize pigments and support nutrient storage in crops, influencing agricultural productivity. Microbial systems harness bacterial membrane vesicles—functionally analogous but structurally distinct—as delivery vehicles for biotechnology and medicine.

Understanding the eukaryotic vacuole challenges the misconception that prokaryotes are “primitive” rather than “different.” The absence of vacuoles reflects adaptive specialization, not evolutionary deficit.

Instead of viewing prokaryotes as lacking compartments, we recognize their specialized membranes serve equivalent, albeit simpler, roles in spatial organization and homeostasis. In contrast, the presence and sophistication of vacuoles unlock new dimensions of cellular freedom, complexity, and evolutionary innovation.

The distinction between eukaryotic vacuoles and prokaryotic membrane adaptations exemplifies one of biology’s most fundamental trends: intracellular compartmentalization as a driver of functional innovation and ecological success. As research advances, vacuoles continue to reveal secrets about cellular organization, evolution, and the intricate engineering of life itself.

Related Post

The Next Big Shift After Erome HD 12: Survival Amid a Turbulent Digital Shift

Valerie Smock WNEP Bio Age Height Education Husband Salary and Net Worth

Hallelujah in the Navy: The Unforgettable Emotional Climax of NCIS Season 13, Episode 18