Unlocking the Secrets of Sodium: How the Bohr Model Explains Na’s Atomic Structure and Unique Chemical Role

Unlocking the Secrets of Sodium: How the Bohr Model Explains Na’s Atomic Structure and Unique Chemical Role

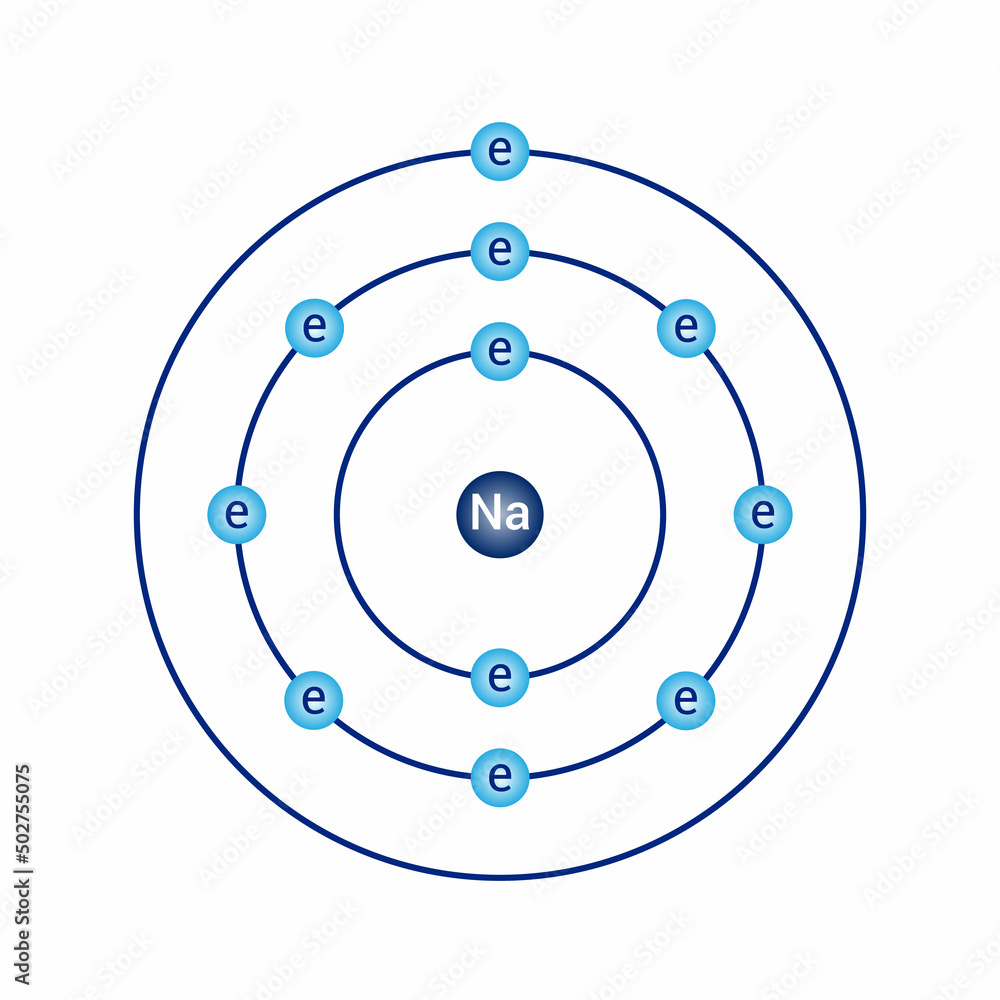

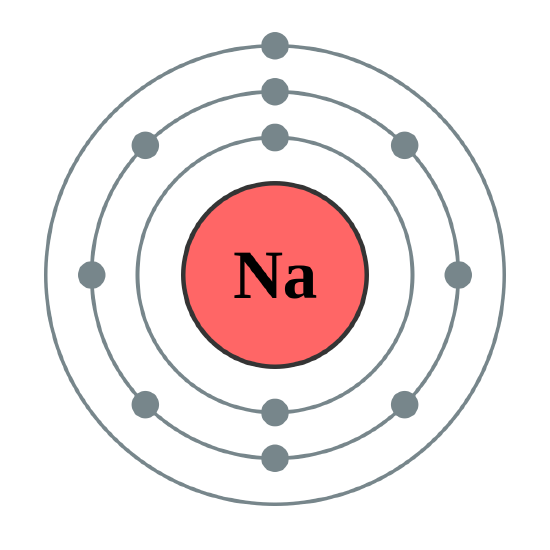

At the heart of understanding sodium’s behavior in chemical reactions lies its atomic architecture, vividly illustrated by the Bohr Model—an essential framework that reveals how electrons reside in fixed energy levels around a sodium nucleus. Na, atomic number 11, exemplifies the dynamic interplay between electron configuration and reactivity, with its single valence electron in the 3s orbital playing a pivotal role. By examining sodium through the lens of the Bohr Model, scientists uncover why this element is highly reactive, conducts electricity so efficiently, and forms ionic compounds with extraordinary ease.

The Bohr Model and Sodium’s Electron Configuration

Niels Bohr’s revolutionary model of the atom, introduced in 1913, posits that electrons orbit the nucleus in discrete energy shells or “shells,” each holding a specific number of electrons.

For sodium (Na), this means an electron configuration of 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s¹—a key detail that defines its chemical identity. “The third electron shell is partially filled, which explains sodium’s eagerness to lose that single 3s electron,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, nuclear physicist at the Institute of Atomic Research.

“This tendency is the foundation of sodium’s ionic character and its role in forming Na⁺ ions.”

Without deeper insight, Na’s reactivity appears accidental—volatile, energetic, and deeply rooted in electron dynamics. Yet, the Bohr Model clarifies that sodium’s outer 3s electron resides in a high-energy shell farther from the positively charged nucleus, making it easier to remove than tightly bound inner electrons. “This electron is not deeply loyal; it’s poised for release, a quality key to sodium’s explosive reactivity with water,” says Dr.

Torres. This ease of electron loss—occurring in just one step after the 3s electron leaves—explains why sodium is classified as a Group 1 alkali metal, exhibiting consistent, sharp chemical behavior across applications.

From Nuclear Electrons to Chemical Logic: How Bohr’s Model Predicts Behavior

Bohr’s quantized energy levels do more than describe structure—they predict reactivity patterns. The outer 3s orbital has a principal quantum number (n=3), meaning its electrons are relatively far from the nucleus and subject to moderate shielding by inner electrons.

This spatial and energetic context enables sodium’s tendency to donate one electron and achieve a stable 2p⁶ configuration resembling neon, the next noble gas. “The energy gap between the 3s orbital and the vacuum is finite but sufficient to allow ejection, yet not so large as to prevent ionization entirely,” notes Dr. Marcus Lin, chemist specializing in periodic trends.

This electron transfer underpins sodium’s iconic properties: high electrical conductivity, malleability, and intense reactivity.

When seated in a compound like NaCl, the 3s electron is shared (or lost) to form electrostatic bonds with chlorine, creating one of chemistry’s most stable ionic lattices. “The Bohr Model’s depiction of energy levels helps explain why that transfer is so energetically favorable—Na donates its valence electron because the transfer lowers the system’s overall energy,” explains Lin. This principle extends to sodium’s role in biology, technology, and industry, where its ion boosts metabolic functions, fuels batteries, and enhances material conductivity.

Visualizing Sodium’s Electron Dynamism

Using Bohr’s concentric orbits, one can assign approximate orbital radii and energy levels that guide how Na interacts with light, matter, and electrons.

In this model: - The 1s orbital (n=1) holds 2 electrons closest to the nucleus, tightly bound. - The 2s and 2p orbitals (n=2) progressively increase energy and electron count, with the 3s orbital (n=3) housing sodium’s reactive valence electron. “The 3s electron’s distance implements a natural window for loss,” says Torres.

“The farther it is from the nucleus, the weaker the electrostatic pull—so it’s more responsive to thermal or electrical stimuli

Related Post

Zip Code For Dia: Unlocking the Power of Precision Zoning Across Northern Virginia

Statewide Legal Services: Powering Justice Through Accessible Legal Aid Across Washington State

Navigating the Pacific Time Zone: Understanding the Current Time Now In Washington Seattle

Altitude In Jackson, Wyoming: The High Country’s Thin Edge Above the Valley