Unlocking the Architecture of Oceanic Carbon: The Vital Lewis Structure Behind OCN

Unlocking the Architecture of Oceanic Carbon: The Vital Lewis Structure Behind OCN

Beneath the wave-driven surface of Earth’s oceans lies a hidden partner in climate regulation—carbonate ions (OCN⁻), the silent architects of marine chemistry and carbon cycling. With Lewis structure analysis, scientists decode the electron arrangement that enables CO₃²⁻ to fulfill its critical role in buffering ocean pH, supporting marine life, and sequestering atmospheric carbon. Understanding the molecular blueprint of OCN⁻ reveals far more than mere geometry—it illuminates fundamental processes underpinning ocean health and global climate resilience.

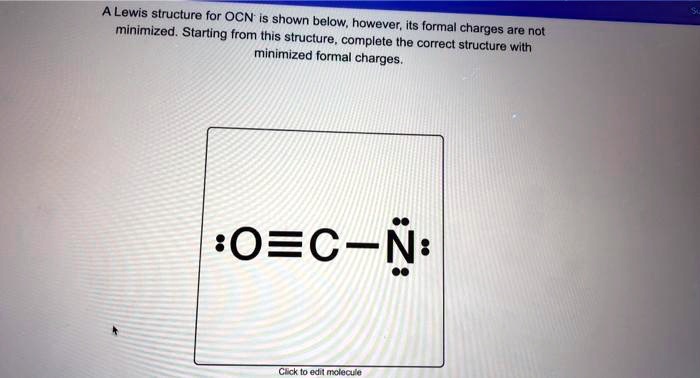

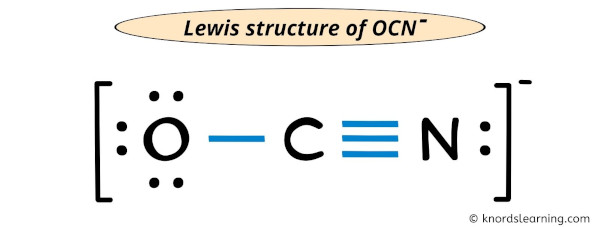

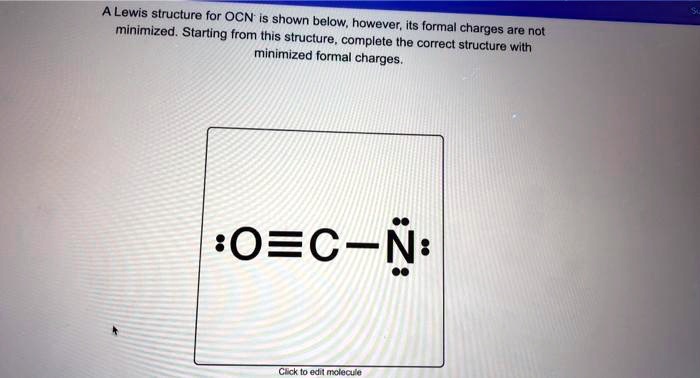

The carbonate ion (OCN⁻) is a polyatomic species defined by three oxygen atoms covalently bonded to one central carbon atom. Its structure emerges from carefully balanced electron sharing, textbook-defined by Lewis dot notation. Carbon, central and electron-deficient, forms partial positive charges, while oxygen atoms—rich in lone pairs—exert stabilizing electron density.

The resulting Lewis structure features three C=O double bonds and one lone pair on carbon, with a net negative charge distributed across the ion. This configuration enables OCN⁻ to act as both an acid (donating a proton to form CO₃²⁻) and a base (accepting a proton to reform CO₂ and H⁺), a duality central to marine carbonate equilibria.

Constructing the Lewis Structure: Electrons, Bonds, and Formal Charges

The formation of the OCN⁻ ion begins with a carbon atom bonded to three oxygen atoms. Carbon, with four valence electrons, shares three pairs with oxygen, forming three single C=O bonds.Each oxygen atom contributes lone pairs and bears one negative charge due to the ion’s overall -1 charge. The Lewis structure reveals: - Three double bonds (C=O), accounting for eight shared valence electrons. - One single bond (implicit C–O, though electron delocalization complicates this simplification).

- One lone pair on carbon, completing its octet. - Each oxygen holds six electrons (three lone pairs), consistent with its -2 formal charge in basic geometry.

Formal charge analysis is essential: carbon’s charge is 0 (4 valence – 4 shared = 0), oxygen atoms each carry –2 (6 nonbonding – (4 + 2)/2 = –2), and the overall ion holds –1.

This charge distribution stabilizes the structure in aqueous environments, influencing reactivity and interaction with other species like H⁺ and metal cations. The resonance nature—though limited due to triple bond constraints—enhances the ion’s adaptability in dynamic marine chemistries.

Resonance and Its Limitations in OCN⁻

Unlike the well-known resonance of cyanide (CN⁻), OCN⁻ lacks extensive delocalization. While multiple Lewis forms could depict electron redistribution between C and terminal oxygens, the true structure reflects limited resonance due to bond strength and electronegativity differences.Oxygen’s greater electronegativity pulls density toward itself, reducing effective double bond character at the terminal site. Still, the resonance-average model remains valuable: it accounts for charge dispersion and explains why OCN⁻ readily participates in acid-base equilibria without excessive instability. This balance between structure and flexibility distinguishes OCN⁻ as both reactive and resilient.

Role in Natural Carbonate Systems

The Lewis structure underpins OCN⁻’s central role in ocean carbonate chemistry. When dissolved, CO₃²⁻ forms coordinate complexes with calcium (Ca²⁺) to produce calcium carbonate (CaCO₃)—the building block of shells, corals, and sediments. The ion’s geometry allows stable complexation, buffering ocean pH by neutralizing acid inputs.Moreover, surface changes during reactions, such as protonation to CO₂, depend on electron distribution revealed by Lewis logic. “The ion’s ability to stabilize charge transitions enables rapid equilibration between dissolved CO₂, HCO₃⁻, and CO₃²⁻,” explains marine chemist Dr. Elena Torres, highlighting the structure’s direct impact on carbon sequestration efficiency.

Measurements confirm OCN⁻ exists predominantly as a linear triatomic ion in water, with bond angles approaching 180°, though local distortions arise from solvation effects and dynamic equilibria. This structural insight guides predictive models of ocean acidification, where declining carbonate ion concentrations threaten calcifying organisms. By mapping electron flow, scientists refine climate projections tied to oceanic carbon sinks—a critical step toward informed environmental policy and conservation strategies.

Application Beyond the Lab: From Theory to Real-World Impact

The Lewis framework for OCN⁻ transcends academic curiosity, influencing environmental monitoring and industrial design.For instance, spectrometers rely on electron configuration data to detect carbonate ions in seawater samples, enabling real-time tracking of ocean chemistry shifts. In carbon capture technologies, mimicking OCN⁻’s binding affinity informs the development of synthetic polymers that sequester CO₂ more efficiently. Such innovations hinge on deep structural understanding: without Lewis theory, optimizing stability, selectivity, and reaction kinetics would remain guesswork.

As global carbon challenges intensify, decoding molecular architecture becomes not just a scientific pursuit, but a practical necessity for planetary health.

In essence, the simple yet precise Lewis structure of OCN⁻ serves as a lens through which the complexity of marine chemistry unfolds. From electron pairs to proton bonds, every configuration tells a story of balance, reactivity, and resilience.

This molecular insight not only satisfies scientific curiosity but equips researchers, policymakers, and stewards with the knowledge to protect Earth’s vital oceanic engines.

Related Post

Unlocking the Secrets of OCN⁻: The Precise Lewis Structure Behind Its Powerful Behavior

Mymedu Ir: Transforming Medical Education, One Irrigation at a Time

Is Cassidy Hutchinson Married or Engaged? The Truth Behind the Public Figure’s Personal Status

The Fight to Preserve Cleveland’s Van Sweringen Tower: A Legacy on the Brink