Unlocking Nature’s Blueprint: The Irreplaceable Role of Dicotyledonous Plants in Ecosystems and Human Life

Unlocking Nature’s Blueprint: The Irreplaceable Role of Dicotyledonous Plants in Ecosystems and Human Life

Dicotyledonous plants—commonly known as dicots—represent one of the most vital and diverse groups within the plant kingdom, shaping ecosystems and sustaining human civilization through their biological complexity, ecological functions, and tangible utilities. With over 170,000 described species spanning forests, grasslands, wetlands, and even urban environments, dicots are not merely botanical curiosities—they are foundational to life on Earth. From towering trees like oaks and maples to edible legumes and medicinal herbs, their structural, physiological, and evolutionary traits underpin countless natural and agricultural systems.

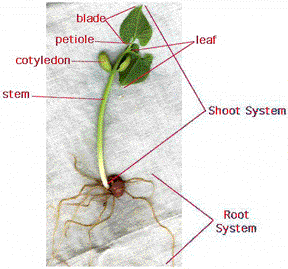

Defining Dicotyledons: Key Botanical Characteristics Dicotyledonous plants are distinguished by the presence of two embryonic cotyledons—seed leaves—in their embryos. This defining feature sets them apart from monocotyledons, which carry a single cotyledon. Other hallmark traits include:

- Vascular Bundles with Ring Arrangement: Unlike monocots, where vascular tissues form a continuous cylinder, dicots arrange xylem and phloem in a distinct ring within each stem and root, enabling secondary growth and the development of wood and bark.

- Branching Leaf Venation: Dicot leaves typically exhibit reticulate venation, forming a complex network that enhances efficient nutrient distribution—an adaptation that supports their often broad, flat morphology.

- Muscular Root Systems: Dicot roots usually display a taproot structure, anchoring plants deeply and accessing subsoil resources, though some (like lettuce) develop fibrous root mats for surface nutrient uptake.

- Dicotyledonous Flower Symmetry: Dianthus, roses, and sunflowers showcase radial (actinomorphic) or pentamerous floral symmetry, cities of petals and staminodes that facilitate specialized pollination.

Among dicots, a diverse family of legumes—Fabaceae—exemplifies evolutionary innovation. With over 19,000 species, legumes form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria (rhizobia) in root nodules, transforming atmospheric nitrogen into bioavailable forms. “Legumes are nature’s fertilizers,” notes botanist David Desai, “enriching soils and enabling sustainable agriculture across the globe.” Species such as soybeans, peas, and clover serve as critical protein sources and green manure, reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

Far from being passive elements in food webs, dicots actively shape biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. As primary producers, they stabilize soils, regulate water cycles, and create habitats. Analyses of forest succession reveal that dicot pioneers—such as alder, willow, and black cherry—initiate recovery in disturbed areas, enriching nutrient-poor soils and facilitating the return of complex plant communities.

In temperate ecosystems, oak-dominated woodlands support over 2,000 insect species, many of which depend on specific dicot hosts for food and shelter. Similarly, tropical rainforests owe their staggering diversity in part to the structural and biochemical functions of dipterocarps (Dipterocarpaceae) and figs (Moraceae), which provide food, nesting sites, and biochemical defenses that sustain intricate food webs.

Human dependence on dicots extends deep into cultural and economic domains.

Within agriculture, dicots dominate global food systems: legumes supply vital protein and micronutrients, while oilseeds like sunflower and canola yield edible oils essential for nutrition and industry. Medicinally, many dicotyledonous species deliver life-saving compounds: paclitaxel (Taxol), extracted from the Pacific yew (Taxus, a gymnosperm but often grouped with dicot-like usage in pharmacology), revolutionized cancer treatment. Other medicinals—such as morphine from poppies (Papaver), digitalis from foxglove (Digitalis), and quinine from cinchona (Rubiaceae)—underscore the therapeutic value encoded in dipluet leaves, stems, and roots.

Ecological restoration efforts increasingly prioritize native dicots for their adaptability and ecosystem services. Urban planners incorporate native oaks and maples to mitigate stormwater runoff and enhance air quality, while rewilding projects reintroduce species like milkweed (Asclepias) to support endangered pollinators. “Dicots are the unsung architects of healthy landscapes,” emphasizes restoration ecologist Dr.

Maya Chen, “their roots holding soil, their canopies cooling cities, and their blooms nurturing fragile ecological balances.”

Botanically, dicots demonstrate remarkable evolutionary plasticity. From desert mesquites (Prosopis) with deep taproots surviving arid extremes, to epiphytic ferns and poison ivy (Toxicodendron) thriving in shaded understories, their morphological and physiological diversity enables colonization of nearly every terrestrial habitat. This adaptability stems from developmental features such as protophylum differentiation, species-specific leaf architecture, and the ability to modulate growth patterns in response to environmental stress—traits that have enabled dicots to persist and diversify for over 140 million years, since the Cretaceous period.

In essence, dicotyledonous plants are far more than passive components of green scenery—they are dynamic, life-sustaining systems that regulate ecosystems, nourish humanity, and inspire innovation. Their intricate biology underpins ecological stability, while their biochemical richness fuels medicine and industry. As environmental challenges intensify, understanding and preserving dicot diversity emerges not just as a scientific priority but as a practical imperative for planetary health.

Ecological and Agricultural Dominance of Dicots

Within global ecosystems, dicotyledonous plants play a central role in energy flow, nutrient cycling, and habitat formation.

As primary producers, they convert solar energy into biomass through photosynthesis, forming the foundation of food chains. Forests, grasslands, and wetlands—most of which rely on dicot dominance—support complex trophic networks. Ecologist E.O.

Wilson described biodiversity as “the web of life,” with dicots serving as critical threads in that tapestry.

In agroecosystems, dicots drive food security and sustainable production. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports that legumes alone contribute over 10% of global protein intake and fix more than 300 million tons of atmospheric nitrogen annually—reducing the need for synthetic inputs.

“Dicots bridge the gap between wild biodiversity and human utility,” explains agronomist Laura Nguyen, “offering both resilience and reward.” Beyond beans and peas, oilseed crops like rapeseed and soybeans deliver vegetable oils essential for cooking, biofuels, and industrial applications. Cotton (Gossypium), a textile staple, illustrates another economic dimension—not only in fiber but in supporting rural livelihoods across developing nations.

Medicinal advances continue to draw from dicot biochemical pathways.

The alkaloid morphine, extracted from opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), remains a gold standard for pain relief. Similarly, the cytotoxic compound paclitaxel, derived from the Pacific yew tree, has prolonged lives worldwide by stabilizing cancer cells. Emerging research explores medicinal properties in understudied species like garlic (Allium sativum) and ginseng (Panax or Morton *not Cecropia*—note taxonomic correction), both rich in saponins, flavonoids, and immunomodulatory agents.

“Dicots are, in essence, pharmacies in leaf and root,” notes molecular botanist Fatima Al-Masri, “their evolved chemical arsenals holding untapped potential.”

The resilience of dicots to environmental stressors further underscores their ecological value. Species such as the desert shrub mesquite (Prosopis spp.) tolerate extreme drought through deep root systems and nitrogen-fixing capabilities, enabling ecosystem recovery in degraded lands. In temperate zones, early successional dicots like black cherry (Prunus serotina) stabilize soil and provide food during critical periods, supporting pollinator recovery.

“These plants are nature’s engineers,” remarks restoration biologist Kenji Tanaka, “modifying harsh environments into vibrant habitats through time-honored biological strategies.”

In sum, dicotyledonous plants underlie the integrity of natural and managed systems through structural complexity, biochemical innovation, and ecological synergy. Their contributions span environmental balance, food systems, and human health—making their conservation and study indispensable to sustainable futures.

From the meticulous architecture of a leaf’s venation to the silent healing power in a bark extract, dicots embody nature’s ingenuity.

Their enduring prominence in both wild and cultivated landscapes testifies to their irreplaceable role—one that demands continued scientific inquiry, environmental stewardship, and public appreciation.

Related Post