Unlocking Energy: How the Spring Potential Energy Equation Powers Innovation

Unlocking Energy: How the Spring Potential Energy Equation Powers Innovation

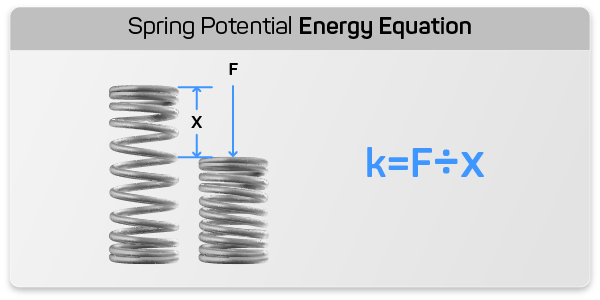

The invisible forces that govern motion and stability underpin technologies far beyond what meets the eye—nowhere is this more evident than in the application of the spring potential energy equation. This fundamental principle of classical mechanics, expressed mathematically as \( E = \frac{1}{2}kx^2 \), describes how energy is stored in a compressed or stretched spring and converted into kinetic energy when released. From biomechanics to engineering systems, this equation is not just a formula—it’s a blueprint for harnessing energy efficiently in dynamic environments.

Understanding the mechanics behind spring potential energy reveals critical insights into system design, energy conversion, and safety. The parameters in the equation—\( k \), the spring constant, and \( x \), displacement—dictate how a spring behaves under load, influencing everything from mechanical oscillators to safety mechanisms in industrial equipment. Engineers rely on precise calculations of stored energy to prevent failures, optimize performance, and ensure reliability in applications where energy storage and release must be controlled with millisecond precision.

The Physics Behind Spring Energy: Core Principles and Equations

At its core, spring potential energy arises from elastic deformation governed by Hooke’s Law: the restoring force \( F \) exerted by a spring is proportional to how far it is displaced from equilibrium, \( F = kx \). This linear relationship forms the foundation for calculating energy stored within the spring. Extending this to energy storage, the integral of force over displacement yields: \[ E = \int_0^x F \, dx = \int_0^x kx \, dx = \frac{1}{2}kx^2 \] This second-order relationship means energy scales with the square of displacement, emphasizing why even small increases in stretch dramatically boost available energy.For rotational or torsional springs, analogous formulas apply with torsional constants, expanding the concept beyond linear systems. The equation’s simplicity belies its power: it enables engineers to predict energy availability, assess mechanical stress, and design components that convert stored energy into useful work. This principle finds relevance in compressed air systems, vibration dampers, and triggering mechanisms across industries.

Engineering Applications: From Machines to Marine Systems

The spring potential energy equation drives innovation across diverse engineering domains. In mechanical systems, torsional and linear springs are essential for precision actuation. Automotive suspensions, for example, use springs to absorb road shocks by storing kinetic energy from impacts—then gradually releasing it to maintain ride stability.A typical car spring might store several hundred joules per spring, sufficient to dampen repeated forces without material fatigue when designed properly. In aerospace engineering, shape-memory alloys and composite springs store and release energy during deployment—such as satellite solar panes or antenna arms that retract or unfold via controlled spring action. These systems require strictly calculated \( kx \) values to prevent overshoot or structural failure in vacuum conditions.

Medical devices also leverage this principle. Prosthetic limbs integrate spring elements to mimic natural muscle elasticity, enabling smoother gait patterns by storing energy during stance and releasing it during swing. This energy return enhances mobility and reduces metabolic cost for users, showcasing the equation’s impact on human-centered design.

Step-by-step: Calculating Spring Energy in Real Systems Applying the spring potential energy formula requires careful measurement and contextual understanding: 1. **Determine spring constant \( k \)** — typically measured via static load tests or calibrated using manufacturer data. For custom springs, strain gauges or dynamic testing identifies elastic modulus under expected loads.

2. **Measure displacement \( x \)** — this is the distance the spring is compressed or stretched from equilibrium. In dynamic systems, peak deflection during peak force may be relevant, not just static position.

3. **Compute energy** — plug values into \( E = \frac{1}{2}kx^2 \). Units are joules, with \( k \) in new

Related Post

Unlocking the Future of Digital Media: Exploring Erome as Your Ultimate Content Hub

Cody Rhodes Believes Dusty Rhodes Wouldnt Like The Size Of His Neck Tattoo