Unlocking Copper’s Secrets: The Lewis Dot Structure That Defines Its Atomic Behavior

Unlocking Copper’s Secrets: The Lewis Dot Structure That Defines Its Atomic Behavior

Copper, a transition metal with the atomic number 29, is celebrated for its exceptional electrical conductivity, malleability, and thermal stability—traits that underpin its essential role in electronics, plumbing, and renewable energy infrastructure. At the heart of understanding copper’s behavior lies its Lewis dot structure, a foundational tool that reveals not just its electron arrangement, but also the chemical and physical phenomena that make copper indispensable. Unlike more rigidly stable elements, copper’s valence electrons exhibit dynamic participation in bonding, a complexity clarified through its dot structure—revealing why copper bonds with metals and nonmetals alike, conducts electricity so efficiently, and develops authentic patinas over time.

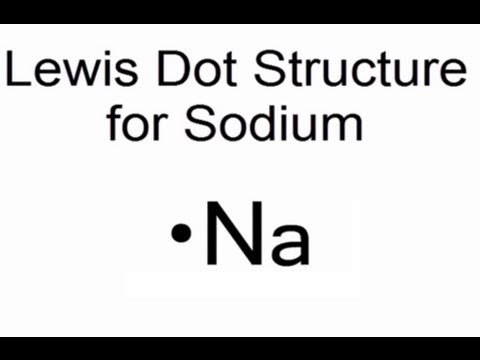

At the core of copper’s electron configuration is a partially filled 3d subshell, positioning it among the transition metals. With atomic number 29, copper’s electron count yields the configuration — [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s¹. This occupancy is pivotal: the single electron in the 4s orbital is loosely bound, enabling copper to form favorable covalent and metallic bonds.

The **Lewis dot structure for Cu** centers on this 4s valence electron—and the unpaired 3d electrons that subtly influence bonding energetics. When copper interacts with ligands or neighboring atoms, these electrons facilitate multiple bonding modes, from simple electron sharing to delocalized electron clouds in metallic lattices.

Examining copper’s dot structure illuminates its characteristic metallic bonding.

In the elemental solid, copper atoms arrange in a face-centered cubic lattice, where delocalized electrons move freely between localized atomic sites. The Lewis model, while simplified, captures this delocalization: the single 4s electron is contributed to the “sea” of electrons, while partially filled 3d orbitals allow flexible electron exchange. This electron mobility is the foundation of copper’s unrivaled electrical conductivity—of all metals, copper ranks highest at ~58 million S/m at room temperature.

As physical chemist Dr. Elena Ramirez notes, “Copper’s ability to sustain electron flow stems directly from its dot structure: a single valence electron ready to shuttle, and supported by a stable d-atom framework.”

Copper’s chemistry extends beyond conductivity. Its valence electron configuration enables versatile redox behavior.

The 4s orbital donates electrons readily in oxidation, forming Cu⁺ (cupric ions with crystal-field energy essential in catalysis) or Cu²⁺ (copper(II) complexes vital in enzymatic systems). Meanwhile, the 3d electrons stabilize intermediate oxidation states, enabling copper to act as both electron donor and acceptor in ligand substitution reactions. For instance, in the formation of chalcocite (Cu₂S), sulfur ligands coordinate to copper, with electrons shifting across d and s orbitals to maintain overall neutrality and lattice integrity.

This dynamic electron behavior—bridging instantaneous bonding and long-term stability—is what Lewis structures render visible.

Beyond molecular chemistry, the Lewis dot structure helps decode copper’s environmental and industrial performance. When copper encounters oxygen and moisture, oxidation proceeds via a surface reaction involving electron transfer: 4Cu + O₂ + 2H₂O → 2Cu₂O (copper(I) oxide) or, in gymnasium-like patinas, Cu₂(OH)₂CO₃ (malachite).

These reactions rely on valence electrons relinquishing energy to form stable oxides and carbonates—processes foretold by dot structure predictions of electron availability. In architecture and conservation, this knowledge guides preservation efforts, as engineers use copper alloys like bronze (Cu-Sn) whose dot structure enhances resistance to atmospheric degradation while maintaining structural integrity.

Further insight into copper’s utility emerges through its bonding preferences.

As a transition metal, copper forms directional covalent bonds when interacting with nonmetals—such as in copper(I) iodide (CuI), where planar d-orbital overlap supports strong coordination. In contrast, metallic bonding dominates in purely metallic contexts, facilitated by the 3d electron cloud’s delocalization. Lewis structures clarify these differences: single paired electrons in ionic unclefts versus extended electron bands in metals.

This distinction is critical in material science—designing superconductors, semiconductors, or corrosion-resistant alloys all hinge on understanding copper’s orbital interactions.

In industrial synthesis, copper’s dot structure informs precise alloy formulation. For instance, brass (80% Cu, 20% Zn) leverages copper’s electron mobility to achieve strength and workability, while bronze retains ductility through electron delocalization across copper-zinc lattices.

Similarly, in cathodic protection systems, copper’s low reduction potential—dictated by its 4s electron energy—makes it effective for sacrificing anodes in marine environments. “The Lewis model isn’t just symbolic,” explains Dr. James Lin, a materials scientist from MIT.

“It reveals copper’s electron fluency—why it conducts, why it oxidizes, and why it’s trusted for centuries.”

Even at the nanoscale, copper’s dot structure governs emerging technologies. In printed electronics and flexible circuits, copper nanoparticles exploit the same electron mobility that powers macroscopic conductors, with quantum effects fine-tuned by surface electron density. Lithium-ion battery anodes increasingly incorporate copper oxides like CuO, where 3d electron participation enhances charge transfer kinetics.

As nanotechnology advances, the fundamental picture drawn by Lewis dot structures remains indispensable—connecting atomic logic to device performance.

In essence, copper’s enduring utility—whether in wiring grids, catalytic converters, or semiconductor components—derives from its atomic arrangement, as visualized through Lewis dot structures. These visual tools distill electron behavior into intuitive symbols, revealing how copper’s valence electrons orchestrate conductivity, reactivity, and stability.

From the periodic table to cutting-edge innovation, copper’s story is written in electrons—and Lewis dot structures decode every chapter. The clarity they provide ensures copper remains not just a metal, but a cornerstone of modern technology.

Related Post

Examining the Phenomenon of Megan Thee Stallion Butt: Cultural Impact and Physicality

Neeplay: Redefining Digital Engagement with Immersive Interactive Entertainment

Sharla McBride WUSA Bio Wiki Age Height Family Husband Salary and Net Worth

Unlocking the Secrets of Mathematics: How Numbers Shape Our World