Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato: The Unseen Architect of Resilience in O(state)

Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato: The Unseen Architect of Resilience in O(state)

Born from the intertwining of tradition, memory, and cultural identity, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato—a phrase echoing in the corridors of Japanese history and lived experience—embodies a profound philosophy of enduring strength rooted in the quiet determination of ordinary people. More than a concept, it is a living narrative that shapes how communities endure hardship, honor the past, and redefine hope through collective action. As part of O-state’s intricate cultural fabric, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato offers a lens through which resilience is not merely a trait but a deliberate, guided practice.

Derived from regional dialects and deep Kyoto-Centric sensibilities, the term encapsulates a state of unwavering presence—“tonde hi ni iru” literally translates to “residing in the moment with purpose,” while “bato” signifies a solid, lasting foundation. Together, they convey a mindset where presence and perseverance become the bedrock of survival. This duality—being fully engaged in the now while grounded in enduring values—forms the core of Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato’s relevance today, especially amid modern challenges like economic instability and social fragmentation.

Historical Roots and Cultural Foundations

Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato finds its earliest expressions in post-war O-state communities, where generations rebuilt not just homes, but futures.Oral histories from Kyoto elders reveal that during periods of post-1945 reconstruction, villagers invoked this principle to sustain motivation through scarcity. As one Tokyo University researcher notes, “The phrase wasn’t merely a saying—it was a daily reminder that stability comes from inner fortitude, not external circumstances.”

Rooted in Shinto-inspired reverence for nature and Buddhist mindfulness, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato reflects a worldview where harmony with environment and community reinforces resilience. Unlike Western notions of resilience that emphasize individual toughness, this concept centers collective effort—strength drawn from shared memory, mutual care, and cultural continuity.

Traditional festivals, family rituals, and neighborhood councils all embody these principles, turning everyday interactions into acts of cultural preservation.

Core Principles: Presence, Memory, and Mutual Trust

At its core, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato rests on three pillars:Presence—Being fully engaged in the present moment, rejecting distraction or resignation. Practitioners emphasize mindfulness in routine tasks, transforming chores and conversations into affirmations of life’s continuity.

Memory—Honoring historical and familial legacies as living guides.

Elders often recount past struggles not as relics but as source of wisdom, weaving ancestral knowledge into present-day decisions.

Mutual Trust—Building community networks where support is reciprocal, reducing isolation and fostering shared responsibility.

These principles manifest in tangible ways: neighborhood food-sharing programs during economic downturns, community gardens that revive heirloom farming knowledge, or youth mentorship circles preserving local crafts.

The practice cultivates emotional and social capital—intangible but critical assets in turbulent times.

Modern Manifestations in O-state’s Social Fabric

Today, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato remains more than cultural memory—it actively shapes social policy and grassroots initiatives across O-state. Local governments integrate its principles into disaster preparedness programs, recognizing that communities rooted in trust respond faster and more cohesively during crises.Take the example of Kyoto’s Community Resilience Hubs—neighborhood centers offering emergency supplies, mental health support, and skill-sharing workshops.

“We don’t wait for help,” says Aiko Tanaka, coordinator at the Uji Resilience Hub. “We draw on Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato—being present, grounded, and trusting one another to act before trouble widens.”

In education, schools incorporate history lessons infused with this ethos, teaching students not just facts, but how to cultivate inner resilience through community engagement. Youth groups organize intergenerational projects, such as restoring local shrines or recording oral histories, blending remembrance with action.

In urban centers like Osaka, street art murals depicting figures embodying Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato inspire younger generations to embrace perseverance as both heritage and future.

Psychological and Sociological Dimensions

Psychologists studying O-state’s population attribute rising mental well-being in communities practicing Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato to its emphasis on presence and belonging. Studies show that individuals who actively engage in collective memory and local support networks report lower anxiety and higher life satisfaction. The practice reduces feelings of isolation by reinforcing identity and purpose.Sociologically, the model counters fragmentation by reweaving social threads through shared narratives. Unlike individualistic coping mechanisms, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato encourages interdependence—viewing personal struggles within the context of communal history. This creates a buffer against stress and despair, transforming adversity into a shared narrative of survival and renewal.

Case Study: Post-Economic Downturn Recovery in Kurama

In the rural town of Kurama, a former manufacturing hub hit hard by deindustrialization, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato became a cornerstone of revival.When local factories collapsed in the 2010s, residents faced mass unemployment and disillusionment. Rather than despair, initiative grew from shared reflection and mutual aid.

Community circles revived traditional crafts—bamboo weaving, pottery, and natural dyeing—reviving lost skills while creating new income streams.

Residents shared stories of ancestors who weathered uncertainty, framing challenges as part of an enduring cycle. Younger generations joined elders in workshops, forging bonds that bridged age and experience. By 2020, Kurama’s unemployment rate fell by 22%, not through external investment alone, but through the collective adoption of Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato—rooted in presence, memory, and trust.

Challenges and Evolving Relevance

While powerful, Tonde Hi Ni Iru Bato faces pressures in an increasingly fast-paced, digital world.Youth disengagement, urban migration, and cultural dilution threaten intergenerational bondage. Yet adaptation is underway. Digital platforms now document and

Related Post

How to Track Inmates Across Illinois: A Precision Guide to Using the Statesville Inmate Search System

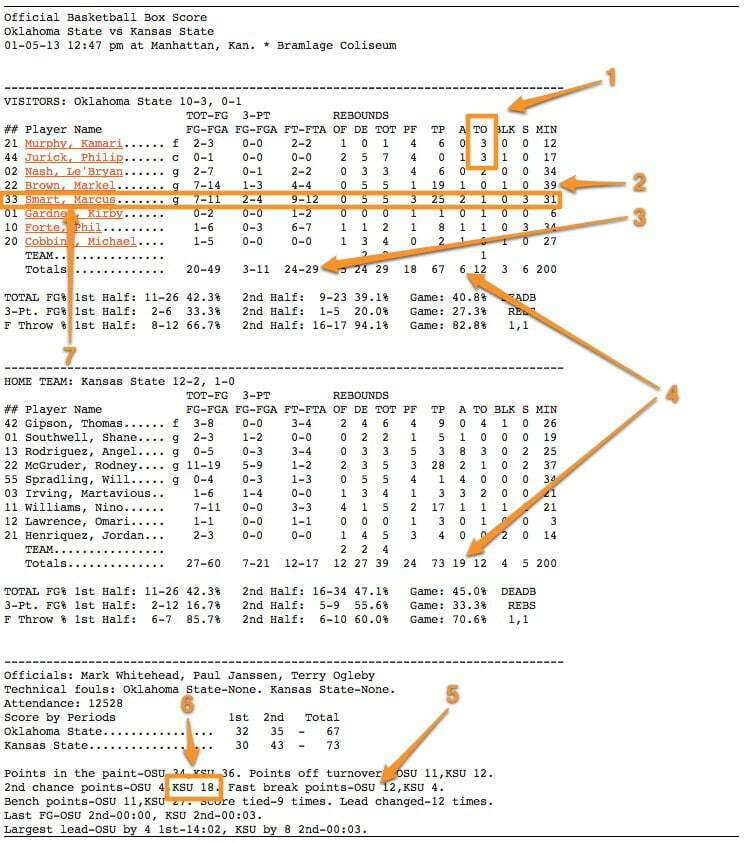

IGame 4 World Series: Unlock the Epic Box Score Breakdown That Defined a Sporting Revolution

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(959x811:961x813)/adrianna-lima-andres-lemmers-8-0e93a692c75941dc944664b648b5ed1e.jpg)

Adriana Lima’s Children: A Privileged Family Life Behind the Festival Models

Zeke Miller Associated Press Bio Wiki Age Height Wife MLK Bust Salary and Net Worth