The Trigonal Planar Bent Bond Angle: A Molecular Secret Shaping Chemical Behavior

The Trigonal Planar Bent Bond Angle: A Molecular Secret Shaping Chemical Behavior

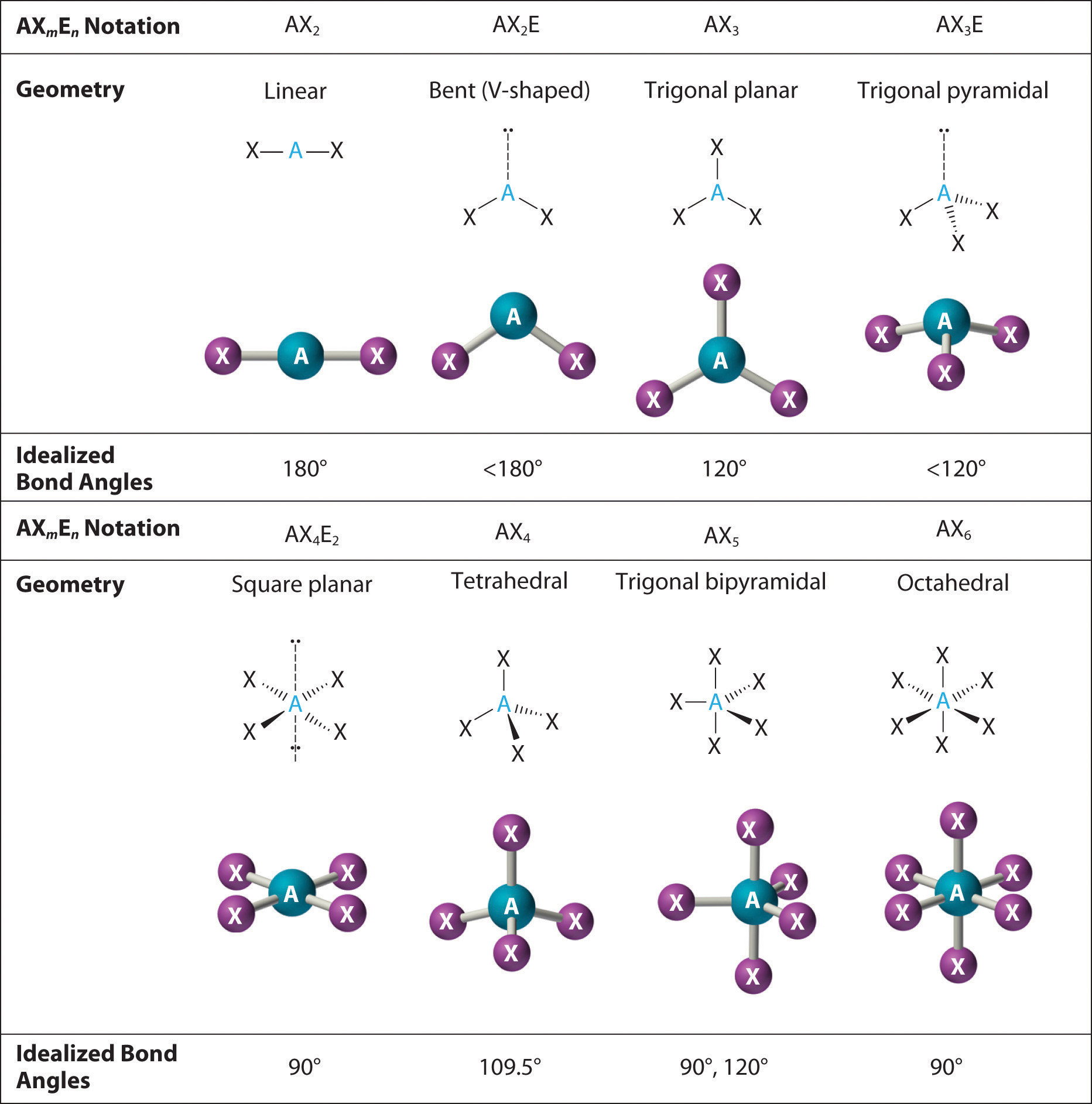

The trigonal planar bent bond angle, typically around 120°, defines a unique structural motif in molecular chemistry—where three atoms or chemical groups converge at a central atom in a nearly flat, symmetrical arrangement, yet subtly distorted by electronic repulsions and bonding demands. This precise angular geometry influences not only how molecules pack and interact, but also their reactivity, polarity, and biological roles. Understanding the trigonal planar bent bond angle unveils a critical balance between ideal symmetry and real-world molecular asymmetry, offering deep insight into everything from molecular design to industrial applications.

At the heart of the trigonal planar geometry lies the concept of sp² hybridization. When a central atom undergoes sp² hybridization—shared with three surrounding atoms or functional groups—it redistributes its atomic orbitals into three equivalent hybrid orbitals oriented approximately 120° apart. “The bond angle emerges from the need to minimize electron pair repulsion,” explains Dr.

Elena Marquez, a computational molecular chemist. “This planar layout maximizes stability, yet subtle deviations occur due to difference in electron density and lone pair contributions.” ### Theoretical Foundations of the Bond Angle The ideal trigonal planar arrangement predicts an angle of exactly 120°, rooted in VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) theory. However, real molecular environments rarely permit such perfection.

Leading bond angles often fall between 118° and 122°, depending on substituent size and electronic effects. For instance, in boron trifluoride (BF₃), a classic example, the 120° angle persists but shows slight compression when electron-withdrawing fluorine atoms impose pull on shared electrons. Factors altering the ideal angle include: - **Hybridization state**: sp² hybrids enforce planarity, but variations in orbital contributions affect spacing.

- **Electron density differences**: Bulky, electronegative substituents induce repulsion, pushing bond angles inward or outward. - **Lone pair presence**: Though rare in trigonal planar frequently assumed to carry no lone pairs, adjacent electron-rich regions can distort geometry subtly. “In reality, the trigonal planar bent bond angle is not a rigid benchmark but a dynamic equilibrium,” notes Dr.

Marquez. “Electronic distribution, steric bulk, and quantum mechanical effects all conspire to fine-tune this angle within a narrow but adjustable range.” ### Impact on Molecular Properties and Reactivity The precise positioning of atoms within a trigonal planar framework directly shapes chemical behavior. The 120° geometry enhances symmetry-driven stability but also creates distinct regions of electronic exposure.

Areas between bonds experience enhanced electron density and reduced shielding, making them prone to electrophilic attack or coordination with metal centers. This is particularly critical in organoboranes and transition metal complexes where such bonding geometries facilitate catalysis and series of organic transformations. In biological molecules, trigonal planar motifs emerge in coenzymes and catalytic triads.

For example, the ketone-enamine tautomer in serine proteases closely resembles the trigonal planar arrangement around the reaction center, enabling precise proton transfers essential for enzymatic function. Quantifying deviations from ideal angles also serves as a diagnostic tool. In materials science, deviations in bond angles within 2D thin films can signal strain, defect formation, or unintended chemical reactions—parameters vital for tuning conductivity, optical properties, and durability.

### Case Study: Boron Trifluoride (BF₃) Boron trifluoride (BF₃) offers one of the clearest illustrations of trigonal planar bonding principles. Boron, diligent with only six valence electrons, forms three robust σ-bonds using sp² hybrid orbitals, leaving a vacant p orbital available for π-backbonding with fluorine. The resulting angle stabilizes the planar structure, with bond angles measured at approximately 120.2°—a testament to VSEPR’s predictive power.

Yet, when exposed to moisture or Lewis bases, hydrolysis disrupts the symmetrical environment, illustrating how external factors redefine this angle dynamically. In contrast, substituted analogs such as sulfur tetrafluoride (SF₄)—though not strictly trigonal planar—demonstrate how lone pairs and expanded octets override ideal geometry, further emphasizing the angular sensitivity governed by electronic rulebooks. ### Experimental Techniques and Measurement Precision Accurately determining bond angles in trigonal planar systems requires advanced characterization.

X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution snapshots, revealing actual bond lengths and angles with sub-angstrom precision. Meanwhile, electron diffraction and spectroscopy—particularly infrared and microwave transitions—probe vibrational modes sensitive to bond geometry, offering indirect but reliable insights. Modern computational methods, including density functional theory (DFT) and ab initio calculations, model electron distribution in 3D space, predicting multiplicative deviations influenced by solvent effects and temperature.

These simulations consistently confirm that bond angles near 120° serve as flexible equilibria, responsive to chemical context. ### Engineering Applications and Industrial Relevance Beyond theoretical interest, trigonal planar bond angles underpin practical chemical innovation. In catalysis, precise bond configurations enable selective bond activation, driving cleaner, more efficient manufacturing processes.

In materials design, tuning bond angles fine-tunes molecular self-assembly for nanotech applications, where symmetry and electronic density dictate mechanical and electronic properties. Drug development leverages this knowledge too: molecules engineered with trigonal planar geometries often exhibit enhanced binding affinity to biological targets, reducing off-target interactions and improving therapeutic profiles.

Ultimately, the trigonal planar bent bond angle is more than a geometric curiosity—it is a linchpin of molecular architecture, where elegance and flexibility coexist to shape reactivity, stability, and functionality.

Mastery of this concept empowers chemists and engineers to invent, predict, and optimize with greater precision in an ever-expanding chemical frontier.

Related Post

The Unscripted Love Life of a Comedy Icon: Unpacking the History of Drew Carey Marriages

Where Jungle Spirits Come to Life: The 1967 Cast That Shaped a Cultural Touchstone

Unveiling The Life Of Shauna Redford: A Journey Through Her Personal And Professional Milestones

What Are Lincoln’s Highest-Paying Jobs? Top 7 Lucrative Sectors Driving the Midwest’s Economy