The Precision of Trigonal Planar Geometry: Decoding Bond Angles That Shape Molecular Behavior

The Precision of Trigonal Planar Geometry: Decoding Bond Angles That Shape Molecular Behavior

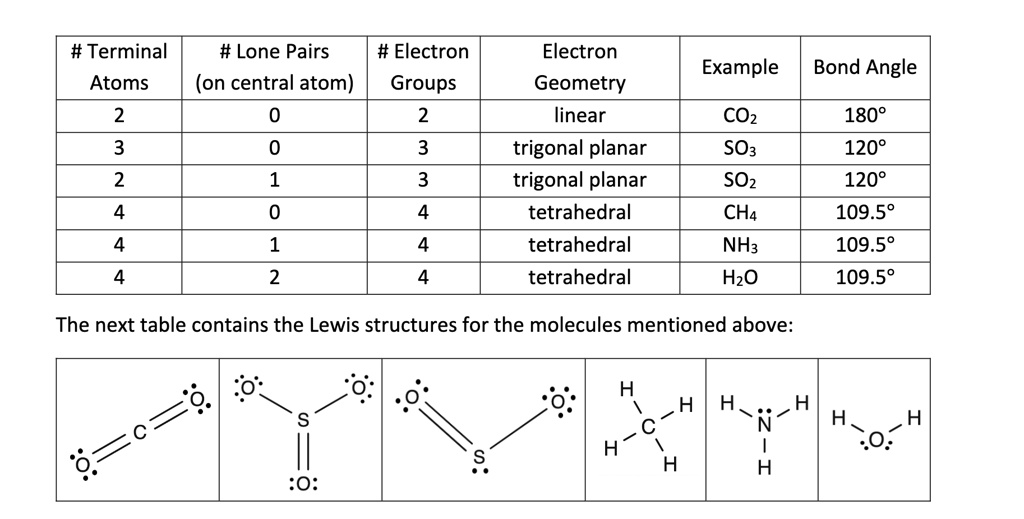

When atoms bond in specific spatial arrangements, their geometry dictates everything from reactivity to physical properties—nowhere is this more evident than in trigonal planar molecular configurations. Central to this arrangement is the bond angle, a classical concept in molecular geometry that defines the 120-degree symmetry observed in common compounds like boron trifluoride (BF₃) and sulfur trioxide (SO₃). The trigonal planar geometry arises when a central atom is surrounded by three bonding pairs of electrons and zero lone pairs, resulting in an equilateral triangle of bonded atoms.

But beyond textbook definitions, understanding the precise bond angle of 120° unlocks deeper insight into chemical behavior, molecular modeling, and material design.

What Defines a Trigonal Planar Molecular Structure?

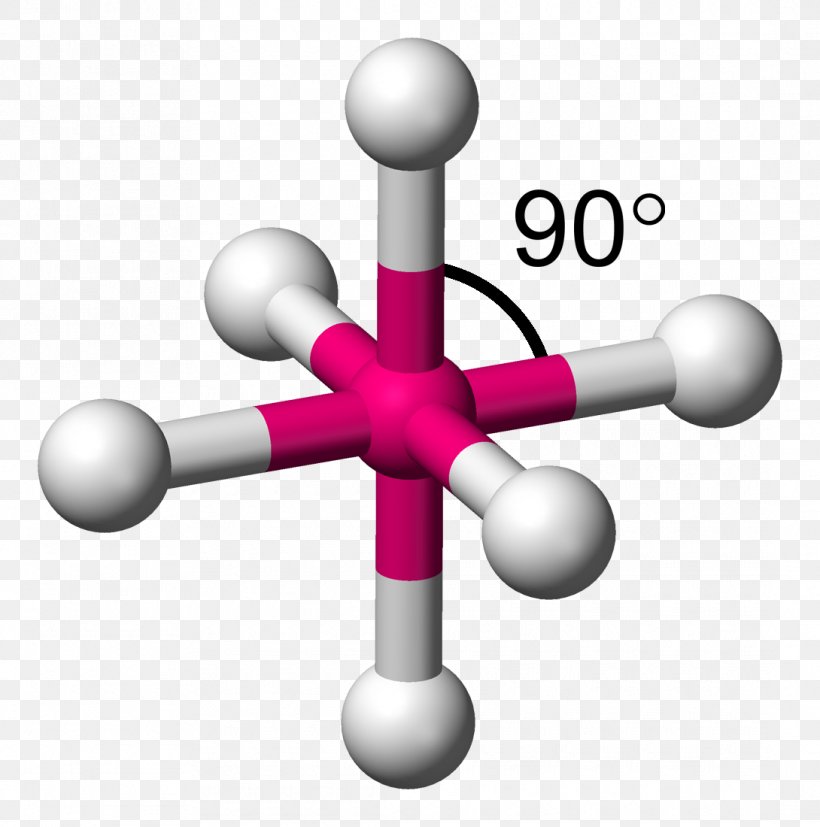

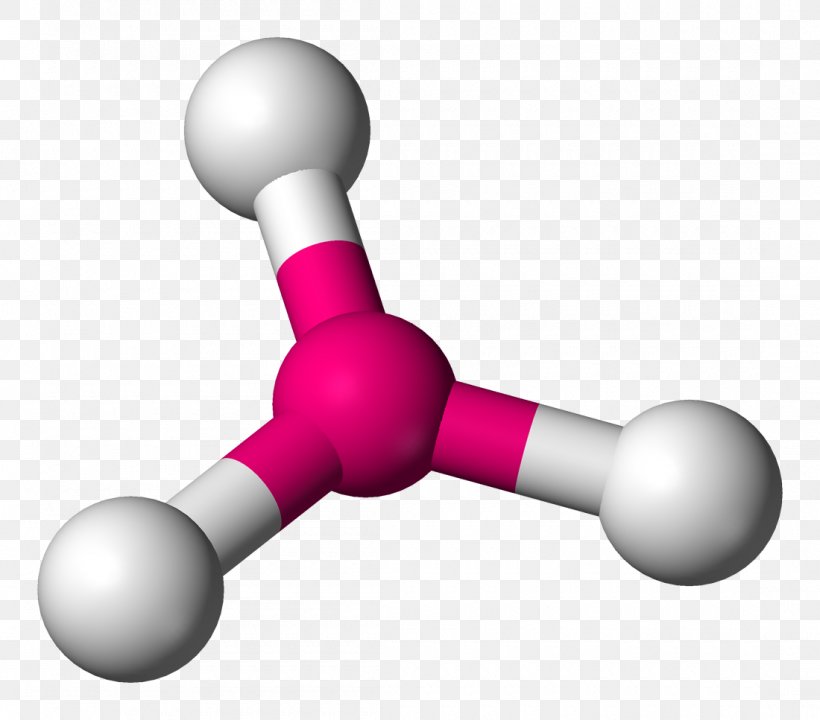

A trigonal planar geometry is characterized by a central atom positioned at the center of an equilateral triangle formed by three bonded atoms, with all bond angles exactly 120 degrees. This symmetrical layout minimizes electron pair repulsion in the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) model, making it a common and energetically favorable configuration for molecules with three equivalent covalent bonds.Key features include: - **Three bonding pairs only**: No lone electrons on the central atom to distort the symmetry - **Maximized spatial separation**: Each bond occupies 120° apart to reduce repulsive forces - **Planar orientation**: All atoms lie in the same flat plane for optimal stability These geometric constraints emerge directly from the sphere-packing principle, where electron density distributes evenly in available orbitals to minimize energy. Trigonal planar shapes are prevalent in inorganic and organic molecules where central atoms like boron, phosphorus, or sulfur form stable electron-dense clusters with minimal polarization.

The Science Behind the 120° Bond Angle

The exact 120° bond angle in trigonal planar systems is rooted in quantum mechanics and orbital hybridization.At the heart of this geometry lies sp² hybridization: the central atom mixes one s and two p atomic orbitals to generate three degenerate sp² hybrid orbitals oriented toward the vertices of an equilateral triangle. Each hybrid orbital then overlaps with a p orbital from the bonded atom, forming σ bonds. The angular spread corridor between these hybrid orbitals naturally closes at 120 degrees, a mathematical necessity for minimizing repulsion.

As Linus Pauling once noted in his foundational work on chemical bonds, “The angle between bonds reflects the balance between electron density concentration and spatial avoidance.” In trigonal planar systems, this balance crystallizes at 120°—a value that harmonizes electrostatic attraction and repulsion. When deviations occur—due to lone pairs, different electronegativities, or steric crowding—the angle often shifts slightly, offering chemists a diagnostic tool to assess molecular strain.

For example, in THF (tetrahydrofuran), the TM bond exhibits a slight angle expansion to ~121° due to lone pair expansion in the ring oxygen, while in boron trifluoride, the true angle remains tightly at 120°, confirming ideal sp² hybridization.

These subtle discrepancies underscore how real-world molecular environments fine-tune geometric perfection.

Real-World Applications and Examples

Trigonal planar geometries are not confined to theory—they manifest prominently across diverse chemical domains. One of the most iconic examples is BF₃, boron trifluoride, a planar molecule critical in organic synthesis as a Lewis acid. The electron-deficient boron center stabilizes through three sp² hybridized orbitals arranged 120° apart, enabling boron to readily accept electron pairs during catalysis and adduct formation.Another case is SO₃, sulfur trioxide, a key intermediate in fertilizer and paint manufacturing. Though often depicted as planar, SO₃ adopts a central sulfur atom surrounded by three oxygen atoms in a perfect trigonal planar layout, facilitating rapid resonance and exceptional chemical reactivity. These structures support the molecule’s role in electrophilic attacks and are exploited in industrial catalysis.

Beyond inorganic compounds, trigonal planar motifs appear in organic species like chloroform (CHCl₃) derivatives and certain fluorophores, where structural precision enables targeted optoelectronic behavior. In materials science, coordination complexes such as trigonal planar ruthenium catalysts use this geometry to control redox activity and substrate orientation, driving advances in sustainable chemistry.

Challenges and Exceptions to Perfect Planarity

While idealized trigonal planar geometry assumes perfect symmetry and 120° angles, real compounds occasionally deviate due to electronic, steric, or environmental factors.Lone pair presence—though absent by definition—can sometimes be mimicked by highly polar bonds or solvent effects that introduce minor angle distortions. For instance, in molecules with strong donor groups adjacent to the central atom, electronic repulsion or polarization may slightly elongate or compress specific angles, rarely exceeding a 2–5° range. Steric crowding presents another challenge: bulky substituents can physically push bond pairs apart, increasing local strain and reducing symmetry.

In such cases, deviations are not random but predictable, reflecting the delicate interplay between structural integrity and molecular bulk. Computational modeling, particularly density functional theory (DFT), now routinely identifies these subtleties, enabling precise prediction of angle shifts in complex systems.

Experts emphasize that while the 120° benchmark is a strong reference, dynamic molecular environments—including temperature, pressure, and solvent polarity—can influence bond angles imperceptibly, especially in flexible or charged species.

Recognizing these nuances strengthens the reliability of trigonal planar geometry as a predictive framework in both academic research and industrial applications.

The Enduring Importance of Trigonal Planar Geometry

The trigonal planar bond angle of 120° stands as a cornerstone in understanding molecular architecture and reactivity. From guiding synthetic pathways to enabling industrial catalysis, this geometric principle bridges fundamental theory and practical utility. As modern chemistry advances toward designed molecules and precision materials, mastery of trigonal planar geometry—its angles, symmetries, and deviations—remains indispensable.Whether stabilizing a reactive core or facilitating electron transfer, this precise 120-degree configuration continues to shape scientific innovation across disciplines, proving that even the most elegant angles carry profound implications.

Related Post

Decoding 'What State Is Va': Unpacking Virginia's Identity and Influence

<strong>The Hidden Edge: The Additive Personality Trait That Transforms Ordinary People Into Exceptionals</strong>

Boyfriends Quaintly Overstepping Boundaries: The Fight That Rocked Relationships in the Spotlight

From One Half to Two: How Cast 2 Redefined Toxic Masculinity with Half Men