The Powerful Insight Behind the Derivative of Ln(x)

The Powerful Insight Behind the Derivative of Ln(x)

The natural logarithm’s derivative, often overlooked, holds profound implications for understanding change, growth, and optimization across science, economics, and engineering. Derived simply from the elegant function \( \ln(x) \), its rate of change reveals how quickly a logarithmic scale responds to input shifts—information that underpins critical models in complex systems. By analyzing this derivative, we unlock a clear perspective on responsiveness, stability, and transformation in natural and human-made processes.

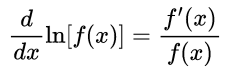

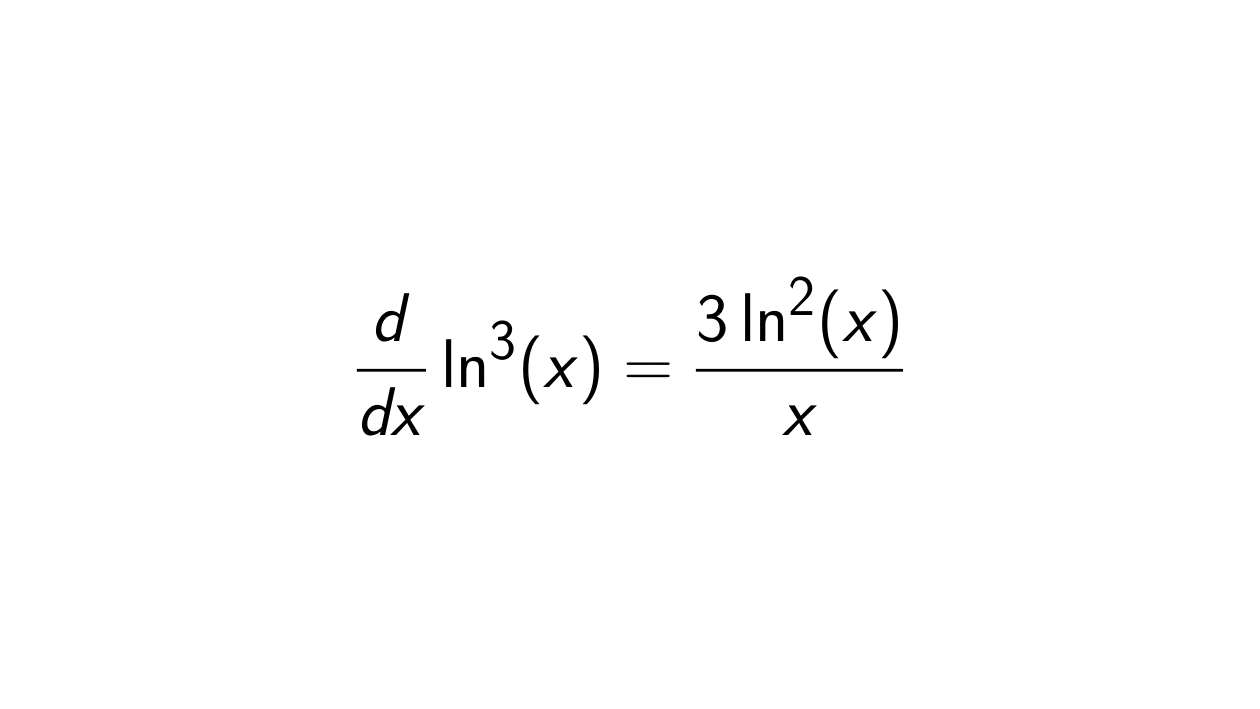

Unveiling the Derivative: The Simple Chain Rule Explanation

At its core, the derivative of \( \ln(x) \) is deceptively straightforward—\( \frac{d}{dx}[\ln(x)] = \frac{1}{x} \).

This result, derived via the power rule and the inverse function relationship, implies that the rate at which \( \ln(x) \) changes diminishes as \( x \) increases. Multiply both sides by \( dx \), and the incremental change becomes \( d(\ln(x)) = \frac{1}{x} dx \)—a concise expression of how closely connected small variations in input are to proportional shifts in output. “The derivative tells us exactly how steep the curve is at any point—not through complex calculations, but through clarity,” notes mathematician Dr.

Elena Torres. “It’s the heartbeat of logarithmic sensitivity.”

Visually, the graph of \( \ln(x) \) reveals a function rising slower as \( x \) grows. This flattening trend corresponds directly to its diminishing derivative: where \( x = 1 \), the rate of change is strongest (\( d(\ln(x)) = 1 \)), but beyond \( x = 1 \), each increase in \( x \) contributes less to the logarithmic growth.

“This inverse relationship between \( x \) and \( \frac{1}{x} \) is foundational,” explains Dr. Marcus Hale, professor of applied mathematics. “It means that at higher values, small increases have less impact—critical for modeling diminishing returns in economics or feedback loops in biology.”

Real-World Applications: From Physics to Finance

This mathematical insight transforms theory into practice.

In physics, the derivative describes how logarithmic scales model entropy changes, where \( \ln(x) \) quantifies information loss. In thermodynamics, small changes in temperature or volume affect logarithmic efficiency metrics precisely by \( \frac{1}{x} \) factors. A key example: radioactive decay rates proportional to \( \ln(N_0/N) \), where \( N \) decreases—here, the rate of decay sensitivity directly depends on \( \frac{1}{x} \), with \( x \) reflecting remaining mass.

In financial modeling, the derivative illuminates risk-adjusted returns.

The Sharpe ratio, though not logarithmic, leverages logarithmic growth in returns: maximizing \( \ln(x) \) path represents maximizing compounded growth with minimizing volatility. “Risk managers use \( \frac{1}{x} \) not explicitly, but the logic lives there—log returns stabilize and rate of change reflects exposure,” clarifies quantitative analyst Fatima Ndiaye. “Every dollar gained at higher value adds less incremental “log-return” than at lower balances.”

Engineers apply this too: when designing control systems, stability hinges on how quickly system outputs respond to inputs.

A logarithmic feedback loop with \( \frac{1}{x} \) sensitivity ensures slow, controlled adjustments—preventing harmful oscillations in aircraft autopilots or robotic limbs.

The Role of Scaling and Context

Understanding the derivative’s shape requires considering scale. Near \( x = 1 \), logarithms grow quickly—ideal for rapid signal amplification or early-stage information processing. As \( x \) climbs, the function flattens, signaling slower adaptation.

“The magnitude of \( \frac{1}{x} \) isn’t static; it’s the context-dependent pace modifier,” observes Dr. Torres. “In sparse, low-value domains, \( \ln(x) \) changes abruptly—except where \( x \) is small and near unity, the derivative spikes, amplifying even tiny inputs.”

This dynamic shapes algorithm design, too.

Machine learning models optimize loss functions using logarithmic transformations (e.g., BLEU scores in NLP), where gradients involve \( \frac{1}{x} \) scaling. Failing to grasp this derivative’s behavior risks inefficient training, slow convergence, or unstable updates—proof that even simple derivatives anchor whole computational ecosystems.

Why This Derivative Matters Beyond the Numbers

Beyond equations, the derivative of \( \ln(x) \) represents a bridge between abstract mathematics and tangible insight. It teaches that change isn’t uniform: logarithmic growth slows as magnitude increases, a principle echoing across nature and human endeavors.

From AI learning rates to climate feedbacks, it reveals how response shrinks with scale—enabling smarter predictions and more resilient systems. “Mathematics isn’t just about solving; it’s about understanding how the world truly changes,” says Dr. Hale.

“The derivative of \( \ln(x) \) offers that clarity—simple, precise, and deeply revealing.”

In essence, the derivative of \( \ln(x) \) is not just a formula—it’s a lens. It sharpens our view on growth, decay, and response, grounding abstract theory in real-world power. For scientists, engineers, and thinkers

.webp)

Related Post

Where Can I Watch The Ball Drop? Your Ultimate Guide to Absolute Spectator Viewing.

What’s That Charge On Your Bank Statement? Decoding Fid Bkg Svc LLC’s Financial Footprint

Unlocking Isp64: The Unseen Power Behind RISC-V’s Maximum Performance Efficiency

From Erome Video 14: The Next Big Shift Reshapes Digital Intimacy and Content Creation