The Molecular Masterpiece: How Lewis Dot Structure Reveals Water’s Unique Power

The Molecular Masterpiece: How Lewis Dot Structure Reveals Water’s Unique Power

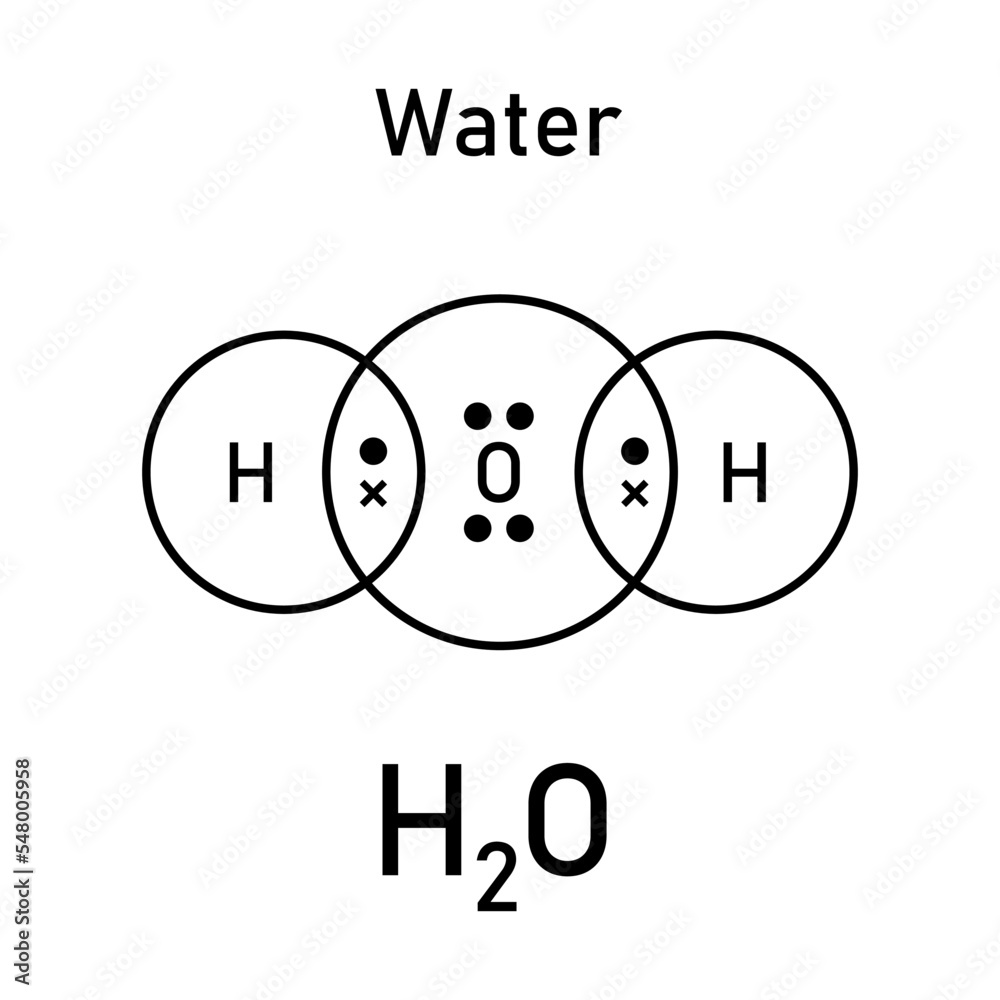

Water, the essence of life, remains one of chemistry’s most remarkable substances — not merely for its biological centrality, but for the elegant simplicity of its molecular architecture. At the heart of water’s exceptional properties lies its Lewis dot structure, a precise visual representation that unlocks the secrets of its bonding, geometry, and reactivity. Understanding H₂O through Lewis models reveals far more than static electron arrangement—it exposes the dynamic foundation for hydrogen bonding, polarity, and the molecule’s role as a universal solvent and reactor.

At its core, the Lewis dot structure of H₂O illustrates a central oxygen atom surrounded by two hydrogen atoms, with shared electron pairs forming covalent bonds. Oxygen, in group 16 of the periodic table, possesses six valence electrons. Each hydrogen contributes one, articulated through the traditional representation: two hydrogen atoms connected via two shared electron pairs (each representing a single bond), while the oxygen maintains two lone pairs.

This configuration yields an electron count of eight around oxygen—complete, stable, yet uniquely configured to enable selective interactions.

The Precision of the Lewis Dot Model in Water’s Structure

The Lewis dot structure of H₂O provides a foundational yet powerful depiction of molecular connectivity. In this model, each bond is symbolized not as a solid line, but as pairs of dots representing shared electrons. The two oxygen-hydrogen covalent bonds occupy central positions, with each bond representing a pair of electrons contributed jointly by atom and atom.Oxygen’s remaining two valence electrons exist as lone pairs—distinct regions of electron density that profoundly influence molecular behavior.

This arrangement dictates key qualitative features: the tetrahedral electron geometry derived from five regions of electron density (two bonds, three regions: two bonds and two lone pairs), however, the molecular shape is bent or angular. The bond angle, measured experimentally at approximately 104.5°, deviates from the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5° due to increased repulsion from lone electron pairs, a phenomenon explained by VSEPR theory. Thus, the Lewis model serves not just as a static blueprint, but as a predictive tool for molecular orientation and reactivity.

Polarity and the Asymmetric Dance of Electrons

One of water’s most consequential traits—its polarity—emerges directly from the Lewis dot structure.Oxygen, electronegativity 3.44, draws shared electrons closer than hydrogen’s 2.20, creating a partial negative charge (δ⁻) on oxygen and partial positive charges (δ⁺) on each hydrogen. This electron distribution is captured in the formal dipole moment, quantified at about 1.85 Debye, confirming water’s polar nature.

This polarity is not abstract—it drives real chemical behavior. In aqueous solutions, water molecules align to shield positively charged solutes, enhancing solubility.

“Water’s polar structure allows it to dissolve more substances than nearly any other liquid,” notes Dr. Elena Rodriguez, a physical chemist at Stanford University. “It’s not just polar—it’s a dynamic polarizer of chemical environments.” The bent geometry further maximizes polarity by preventing full cancellation of dipole moments across the molecule.

The Science of Hydrogen Bonding and Cohesion

Beyond polarity, the Lewis model clarifies the origin of hydrogen bonding—one of water’s defining macroscopic properties. Each hydrogen atom, carrying a δ⁺, approaches the δ⁻ oxygen of a neighboring water molecule, forming a hydrogen bond. Though weaker than covalent bonds, these interactions are far more persistent and abundant in bulk liquid water.This intermolecular force explains water’s high cohesion and surface tension—critical to capillary action, biology, and climate regulation.

At 25°C, over 90% of liquid water molecules participate in at least one hydrogen bond, creating a cohesive network that resists deformation. The same model also reveals why water exhibits anomaly in density: because hydrogen bonds resist full compression, ice forms a lighter lattice, floating and insulating aquatic ecosystems.

Other molecular interactions, such as ion solvation and dipole-dipole attractions, further underscore the Lewis framework. When an ionic compound like NaCl dissolves, the polar water structure orientates—oxygen δ⁻ faces Na⁺, hydrogen δ⁺ faces Cl⁻—a process driven by electrostatic complementarity laid bare by electron-pair counting.

Dynamic Behavior: Beyond the Static Diagram

While the Lewis dot structure captures a moment frozen in time, water’s true dynamism emerges when viewed through motion and thermodynamics.Electrons in H₂O are not static; they constantly shift, enabling rapid reorganization during hydrogen bond formation and breakage. This dynamic equilibrium supports water’s role as a versatile solvent and reactant.

For instance, in acid-base chemistry, water acts as both donor and acceptor: its δ⁺ hydrogens facilitate proton transfer, while lone pairs on oxygen serve as nucleophiles. The Lewis model illustrates these reversible interactions clearly, showing how the molecule’s electronic flexibility underpins catalytic roles in hydrolysis, hydration, and enzymatic reactions.

Even thermal behavior reflects this complexity.

Because broken hydrogen bonds require energy input—about 40.7 kJ/mol per bond—liquid water resists rapid temperature changes, contributing to Earth’s thermal stability and seasonal moderation.

Environmental and Biological Implications

The Lewis dot structure of H₂O is not merely academic—it is foundational to understanding global systems. In the biosphere, water’s polarity and hydrogen bonding enable cellular transport, nutrient absorption, and macromolecular folding. Proteins and DNA rely on water’s solvent properties and dynamic interactions to function, while metabolic pathways hinge on hydrogen bond dynamics and proton transfer mechanisms.On planetary scales, water’s cohesion and high heat capacity—both rooted in molecular polarity—regulate climate and enable weather cycling.

“Every cloud, every raindrop, stems from molecular design,” says Dr. Samuel Tran, atmospheric chemist at NASA. “The Lewis dot structure encodes the very forces that sustain life on Earth.”

A Blueprint of Interconnected Chemistry

The Lewis dot structure of H₂O transcends a simple electron map—it is a gateway to understanding one of the most behaviorally rich molecules known.By revealing connectivity, geometry, and charge distribution, it explains polarity, hydrogen bonding, and reactivity with clarity and precision. This model bridges atomic theory and observable phenomena, illustrating how molecular architecture shapes macroscopic reality. From biological systems to planetary climates, water’s story begins at the atomic scale—where dots and bonds craft a substance that powers existence.

As science continues to probe molecular dynamics, the Lewis structure remains an indispensable lens, transforming static diagrams into living narratives of chemical life.

Related Post

Master Server-Side Ped Spawning in FiveM: The Ultimate Guide to Efficient In-Game Ped Infrastructure

US Bank ATM: Max Withdrawal Limits Explained