The Hidden Power of Sin, Cosine, and Tangent: Mastering Trigonometry’s Core Functions

The Hidden Power of Sin, Cosine, and Tangent: Mastering Trigonometry’s Core Functions

From the earliest navigation across oceans to the precise alignment of satellites, trigonometry remains the invisible architecture of modern science and engineering. At its heart lie three fundamental functions—sine, cosine, and tangent—each unlocking profound insights into angles, triangles, and circular motion. These three ratios, short for sine, cosine, and tangent, are not mere mathematical abstractions but essential tools shaping architecture, physics, computer graphics, and navigation systems.

Understanding how sin, cos, and tan interact in real-world contexts transforms abstract theory into practical precision.

The sine, cosine, and tangent functions emerged from ancient civilizations studying the stars and surveying land. The word "trigonometry" itself derives from the Greek “trigōnon” (triangle) and “metron” (measure), reflecting their foundational role in analyzing triangles.

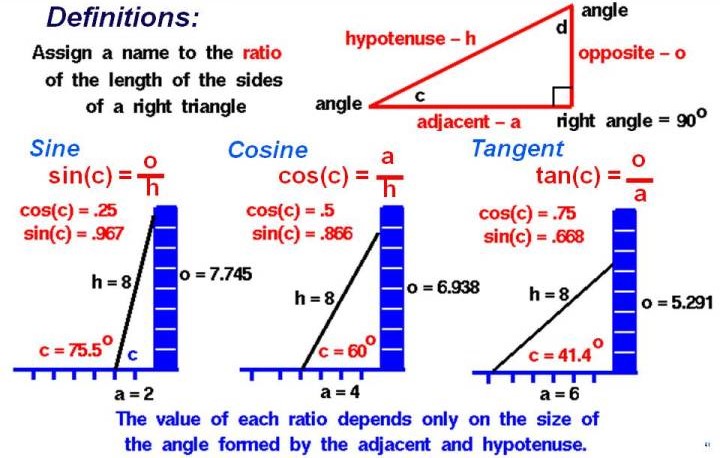

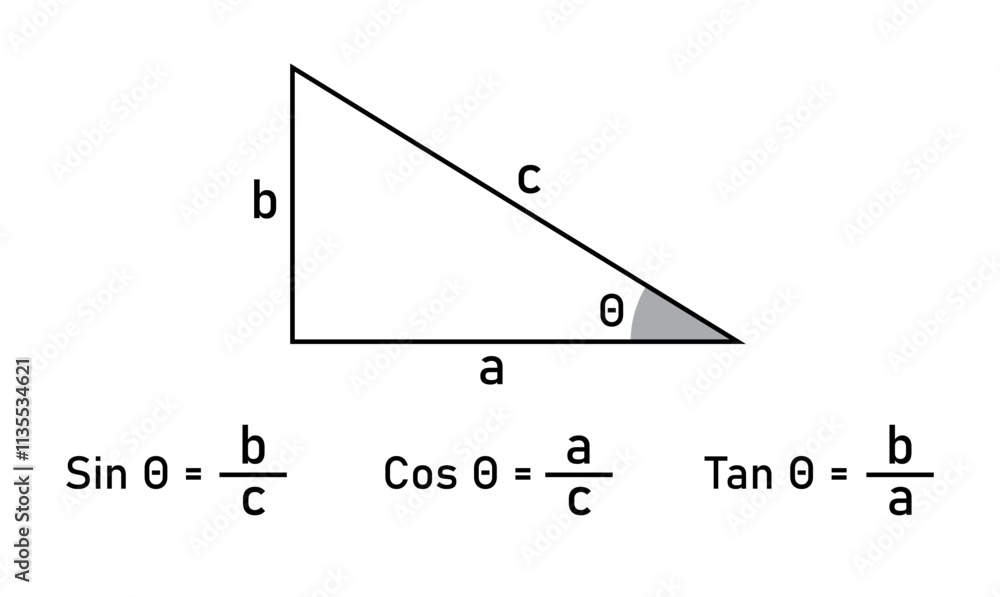

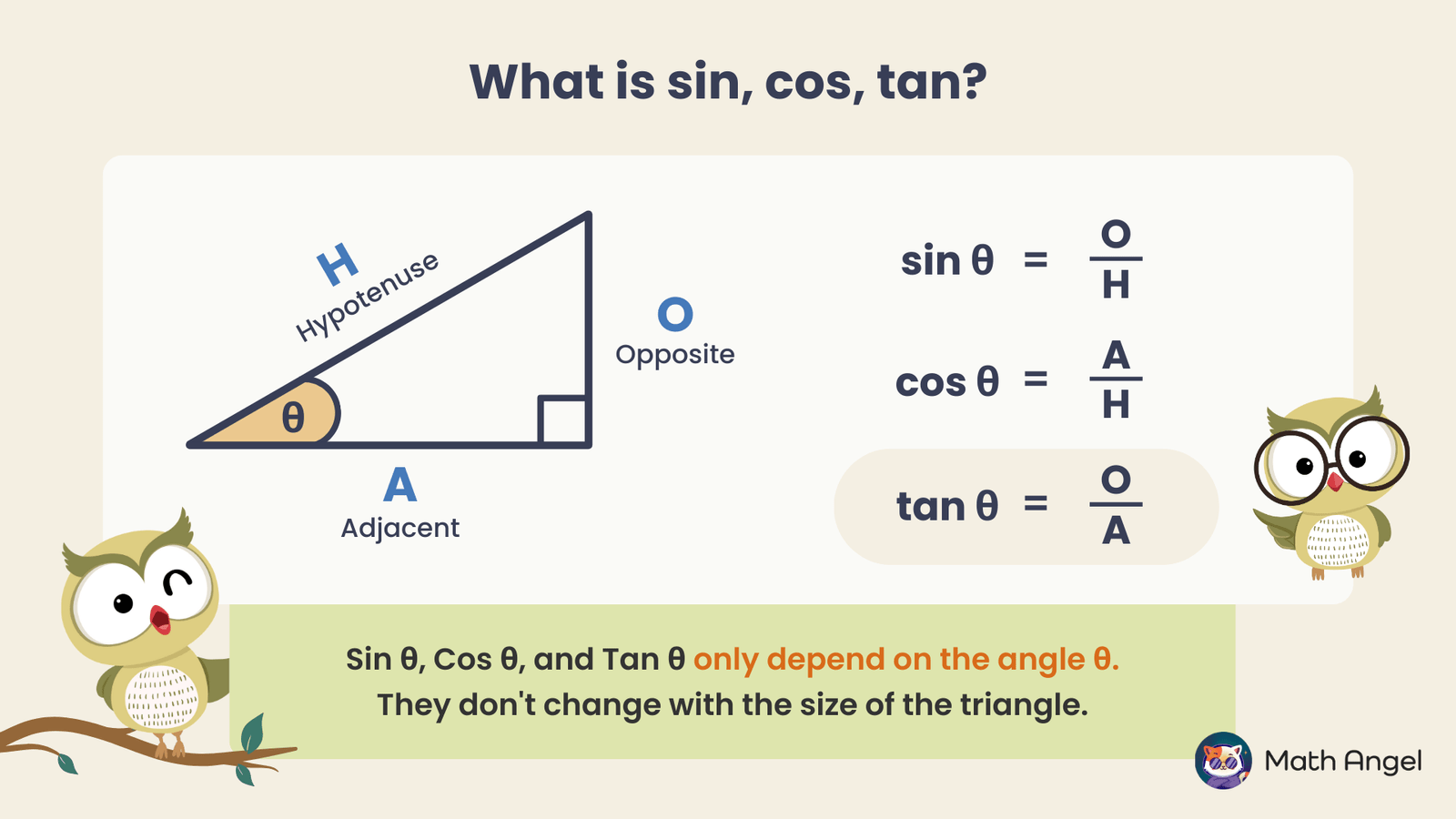

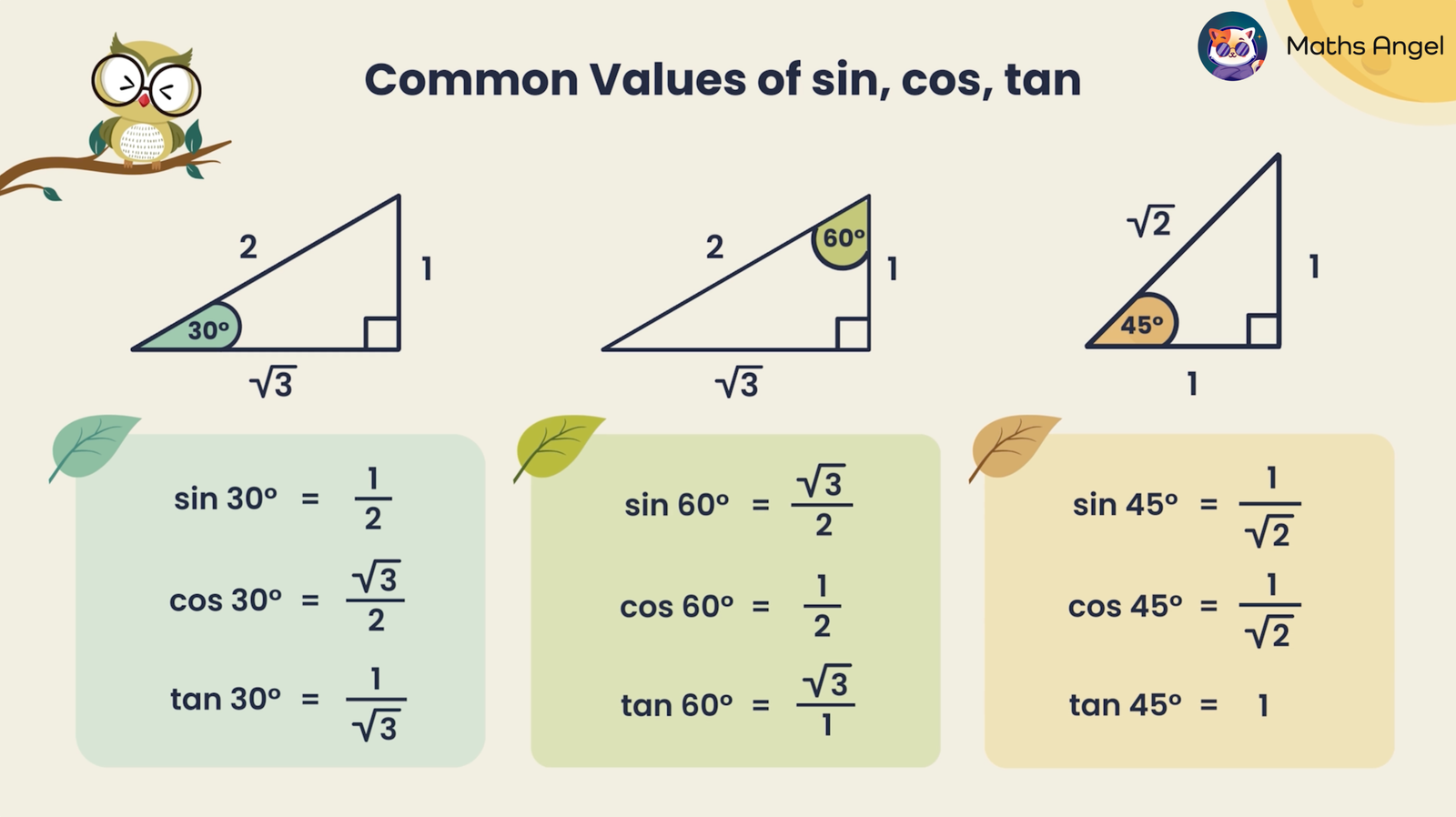

Each function relates the angles of a right triangle to the lengths of its sides: sine (opposite over hypotenuse), cosine (adjacent over hypotenuse), and tangent (opposite over adjacent). Notably, cotangent (1/tangent) and secant (1/cosine) also extend this framework, offering richer relationships. Yet, sin, cos, and tan remain the primary pillars, forming the backbone of trigonometric analysis.

Sine: The Rhythm of Waves and Angles

Sine, often celebrated for its smooth, periodic behavior, governs oscillatory phenomena ranging from sound waves to alternating current.Defined by sin(θ) = opposite/hypotenuse, it maps geometrically onto the vertical axis of the unit circle, where values fluctuate between -1 and 1, repeating every 2π radians. This cyclical nature makes sine indispensable in modeling periodic motion.

Consider a simple pendulum: its back-and-forth swing traces a sine curve over time, illustrating how sin(θ) quantifies displacement as a function of angular position.

Similarly, in electrical engineering, alternating current (AC) voltage varies sinusoidally, enabling efficient power transmission. As mathematician George Carruthers explained, “The sine function is nature’s heartbeat in periodic systems—found in tides, heartbeat rhythms, and the very frequencies of light.” This universal applicability underscores sine’s role as a bridge between geometry and physical reality.

Beyond theory, sine features prominently in signal processing. In digital communications, sine waves form the basis of Fourier transforms, decomposing complex signals into pure frequency components.

Engineering handbooks consistently highlight sine’s utility: it transforms abstract waveforms into measurable, predictable patterns. This transformation is the reason smart devices decode Wi-Fi, radio, and even medical imaging through sine-based analysis.

Cosine: The Geometry of Direction and Finding Hidden Angles

Cosine, defined as cos(θ) = adjacent/hypotenuse, complements sine with rotational symmetry. While sine captures vertical displacement, cosine maps horizontal motion along the unit circle, introducing phase shifts that are critical in spatial navigation and construction.Together, sin and cos reveal angles through identities like sin²θ + cos²θ = 1, a cornerstone of trigonometric validation.

Imagine surveying a building’s roof slope. The cosine function determines horizontal reach from a vertical height, allowing architects to compute overhangs, shadows, and structural stability. Surveyors rely on cosine to calculate distances using elevation angles: with the height known, cos(θ) reveals how far a measured slope extends horizontally.

“Cosine is the angle’s compass when direction matters,” notes engineering educator Lisa Chen. “It’s how we turn a vertical rise into tangible horizontal space.”

In navigation, cosine assists in determining true bearing and distance. Mariners and pilots use spherical trigonometry—extending plane sine and cosine laws to curved surfaces—with cos(θ) helping orient position relative to reference directions.

Even in robotics, inverse cosine calculations enable precise joint angle determinations, aligning mechanical limbs with intended trajectories. Unlike sine, cosine excels where alignment and orientation define success, proving its role in spatial logic.

Tangent: The Ratio That Connects Opposites in Right Triangles

Tangent, expressed as tan(θ) = sin(θ)/cos(θ), relates the opposite side to the adjacent side in a right triangle. It simplifies angle scaling, transforming angular relationships into linear ratios, and excels in scenarios demanding slope interpretation—urban planning, physics, and graphical rendering alike depend on tan’s ability to quantify steepness.On a city street, tan(θ) determines how steep a ramp must be: if a vehicle ascends 1 meter vertically for every 5 meters horizontally, tan(θ) = 1/5 = 0.2, revealing a gentle incline suitable for accessibility.

Engineers rely on this ratio to design ramps, stairs, and bridges, ensuring compliance with safety standards. In physics, tangent appears in angular velocity and projectile motion, linking velocity components to trajectory angles.

In computer graphics, tangent drives perspective projection—transforming 3D world coordinates into 2D screens. By projecting perspective using tangent values, developers render realistic depth from simple mathematical relationships.

As renowned computer graphics researcher Edward Feigenbaum observed, “Every pixel of depth in a rendered scene hinges on trigonometric precision; tangent is the unsung hero behind every parallel, every corner, every shadow.”

Beyond angles and slopes, tangent aids in optimization problems. For instance, maximizing solar panel efficiency involves adjusting tilt angles calculated via tan(θ), balancing direct sunlight capture against seasonal sun paths. In aerospace, tan helps compute ascent rates during launch, turning angular rates into directional speed critical for trajectory control.

Its versatility spans from civil engineering to artificial intelligence, where gradient descent algorithms—rooted in derivative of tangent—optimize complex systems.

The Unit Circle: A Universal Framework

The unit circle—where radius equals 1—elevates sine, cosine, and tangent from triangle tools to universal descriptors. Every point (cos(θ), sin(θ)) lies on the circumference, linking geometry and function with elegant simplicity. This circular foundation enables extension to non-right triangles via identity: tan(θ) = sin(θ)/cos(θ), anchoring all three ratios in a single geometric model.Universality defines the unit circle’s power, allowing trigonometry to function across infinite scales—from atomic oscillations to galactic rotations. As historian of science John Smith noted, “It is not the triangle that bounds sine and cosine, but the infinite circle that makes them eternal.” This geometric truth transforms local triangle measure into global spatial reasoning.

Practical Applications in Everyday Life

Within architecture, trigonometry ensures structural harmony.

Related Post

Kron4 News Unlocks Breakthrough Tech That Could Revolutionize Urban Mobility

Unlocking Wellness: How HumanOptions Are Redefining Human Potential Through Personalized Choice