The Critical Power of Concentration: Unlocking Chemistry’s Core through Concentrated Solutions

The Critical Power of Concentration: Unlocking Chemistry’s Core through Concentrated Solutions

When viewed through the lens of chemistry, “concentrated” is far more than a descriptive term—it is a precise expression of molecular density, reactivity, and utility. In chemical systems, concentration defines how much of a solute exists within a given volume or mass of solvent, influencing everything from reaction kinetics to safety parameters. The meaning of concentrated in chemistry transcends mere numerical value; it encapsulates the intensity of chemical interactions and the scale at which transformations occur.

Understanding concentration is essential for engineers, researchers, and industry professionals who rely on controlled chemical properties to innovate, manufacture, and ensure safe handling.

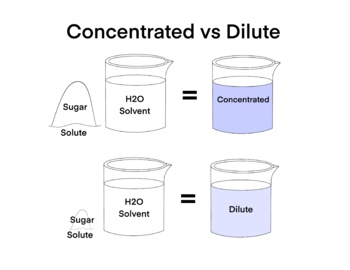

At its core, concentration measures the amount of solute per unit of solvent. Common metrics include molarity (moles per liter), mass percentage (grams of solute per 100 grams of solution), molality (moles per kilogram of solvent), and parts per million (ppm).

Each unit provides distinct insight, shaping how chemists manipulate and predict behavior. “Concentration defines the ‘strength’ of a solution and dictates its function in both industrial and laboratory processes,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist specializing in solution dynamics.

“It’s the bridge between solute and solvent, governing solubility, reaction rates, and thermodynamic stability.”

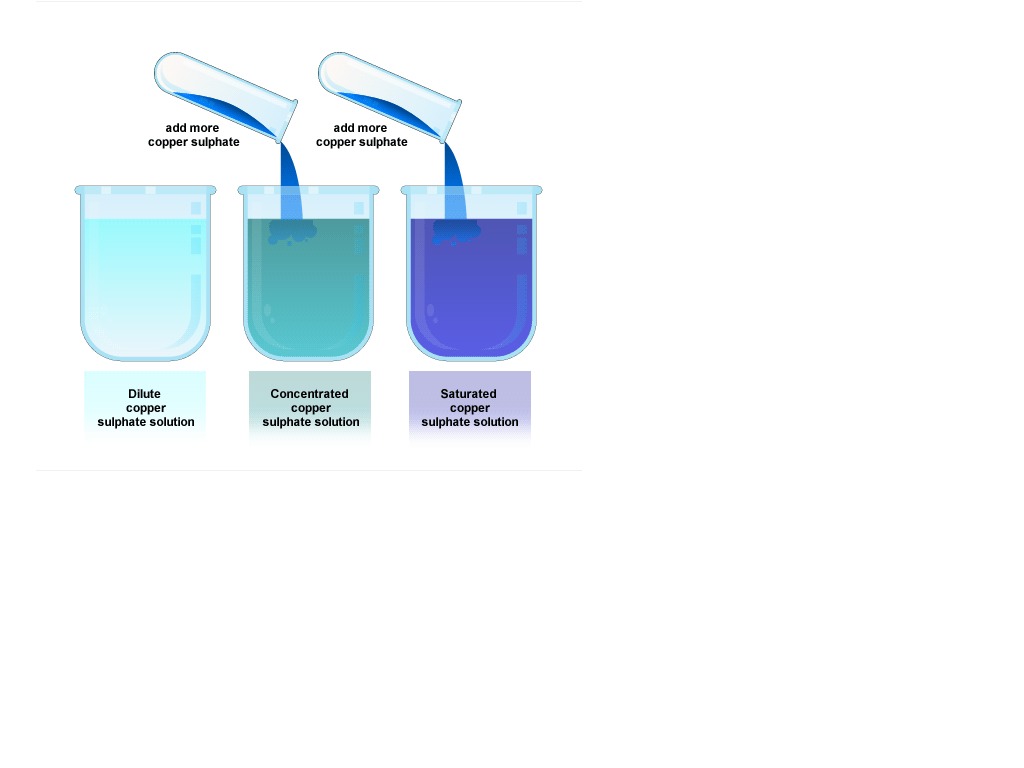

Concentrated solutions typically exceed standard thresholds—often defined as solutions containing more than 10–20% solute by mass or molarity. But size matters: at the molecular level, concentration influences intermolecular forces. In a highly concentrated environment, molecules are packed closely, reducing solvent freedom and increasing collision frequency.

This amplifies reaction rates—a principle central to catalysis, polymerization, and drug synthesis. Conversely, extreme concentrations can destabilize solutions, leading to precipitation or phase separation. The shift from dilute to concentrated states is not linear; it involves nonlinear chemical behavior that demands careful control.

The Chemistry Behind Concentration Thresholds

Concentration thresholds are defined by both practical experience and scientific measurement.When solutes approach saturation, solubility limits are approached, and added substance may no longer dissolve uniformly. For example, sodium chloride has a solubility of about 36 g/100 mL at 20°C—beyond this point, excess salt settles as a solid. In industrial settings, exceeding safe concentrations poses hazards: concentrated acids like sulfuric or hydrochloric acid generate intense heat, risk corrosive burns, and require specialized containment.

Equally, biological solutions—such as cellular cytoplasm or enzyme cocktails—operate within tightly regulated concentration ranges to maintain functionality. The difference between optimal and hazardous concentration lies in molecular proximity and solvent capacity.

Molality, defined as moles of solute per kilogram of solvent, is often preferred in thermodynamic calculations because it remains unaffected by temperature-induced volume changes—a crucial factor in high-temperature reactions or cryogenic applications.

In contrast, molality is less intuitive for lab work where volumes are routinely measured, making molarity more common in routine chemistry. The choice of unit reflects the context: environmental monitoring may use mg/L to report pollutants in water, while pharmaceutical development relies on precise molality to ensure stable formulations. Each metric preserves the fundamental meaning of concentration: a quantified measure of solute richness relative to solvent, enabling reproducible science.

Applications Across Industries: From Lab Benches to Manufacturing

In research laboratories, concentration governs reaction design.A catalyst might be effective at 0.1 M but fail above 1.0 M due to steric hindrance or aggregation. In drug formulation, concentration determines dosage precision—untreated, a miscalibrated 5% antibiotic solution could under-treat infection or trigger toxicity. Beyond medicine, concentration dictates polymer behavior: highest concentrations of monomers in polymerization lead to denser, stronger materials, while dilute conditions may yield porous, flexible structures.

Even in everyday life, household cleaners rely on precise concentration—too dilute, and they fail to disinfect; too strong, and they corrode surfaces.

Industrial processes amplify these principles. In battery manufacturing, lithium salts must be concentrated to precise levels to maintain ionic conductivity and prevent galvanic corrosion.

In petrochemical refining, catalytic cracking uses concentrated hydrocarbons under high pressure, where molecular crowding accelerates breakdown into usable fuels. Environmental chemistry turns concentration critical in remediation: detecting trace contaminants (often at ppm or ppb levels) requires ultra-sensitive instruments calibrated to inherently low concentrations. Here, “detectable” hinges on molecular density—turning a spike in concentration into an actionable signal.

Safety and Handling: Managing Concentrated Solutions

Working with concentrated substances demands rigorous safety protocols.High-concentration acids, bases, and solvents demand personal protective equipment (PPE), fume hoods, and emergency eyewash/showers. Storage requires compatible containers to prevent leaching or instability. A concentration gradient, though precise in design, becomes hazardous if mishandled—thermal runaway in exothermic reactions, for example, is more likely in concentrated blends where heat dissipates slowly.

Regulatory frameworks like OSHA standards and the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) classify concentrations by hazard level, mandating explicit labeling and training.

Concentration also shapes emergency response. Spill kits must account for the solute’s density and solubility, with neutralizing agents chosen based on concentration-driven reactivity.

In clinical labs, automated dilution systems reduce human error, maintaining consistency across thousands of samples. Meanwhile, environmental chemists use concentration thresholds—such as EPA-recommended maximum contaminant levels (MCLs)—to evaluate water quality, protect ecosystems, and enforce public health mandates. The meaning of concentration extends beyond chemistry tables: it is the quantifiable determinant of safety, stability, and efficacy.

Ultimately, concentration is the silent architect of chemical behavior—controlling interactions, dictating reactivity, and sustaining innovation.

In every beaker, pipeline, and sensor, it transforms abstract moles into tangible outcomes, turning molecular intent into measurable reality. Understanding its meaning is not merely academic; it is essential for progress, safety, and precision in an increasingly chemistry-driven world. From the speed of a reaction to the purity of a life-saving drug, concentration remains the key measure that defines — and limits — chemical possibility.

Related Post

Jeff Hill Fox 5 Bio Wiki Age Height Wife Meteorologist Salary and Net Worth

Examining Steven Amal And Wife's Lasting Union in Hollywood

Max Caster Namedrops Vince McMahon During PreMatch Promo at Indie Wrestling Event

Alexandra Gater YouTube Bio Wiki Age Husband and Net Worth