The Boston 1773 Tea Party: The Flaming Spark That Lit the Revolutionary Flame

The Boston 1773 Tea Party: The Flaming Spark That Lit the Revolutionary Flame

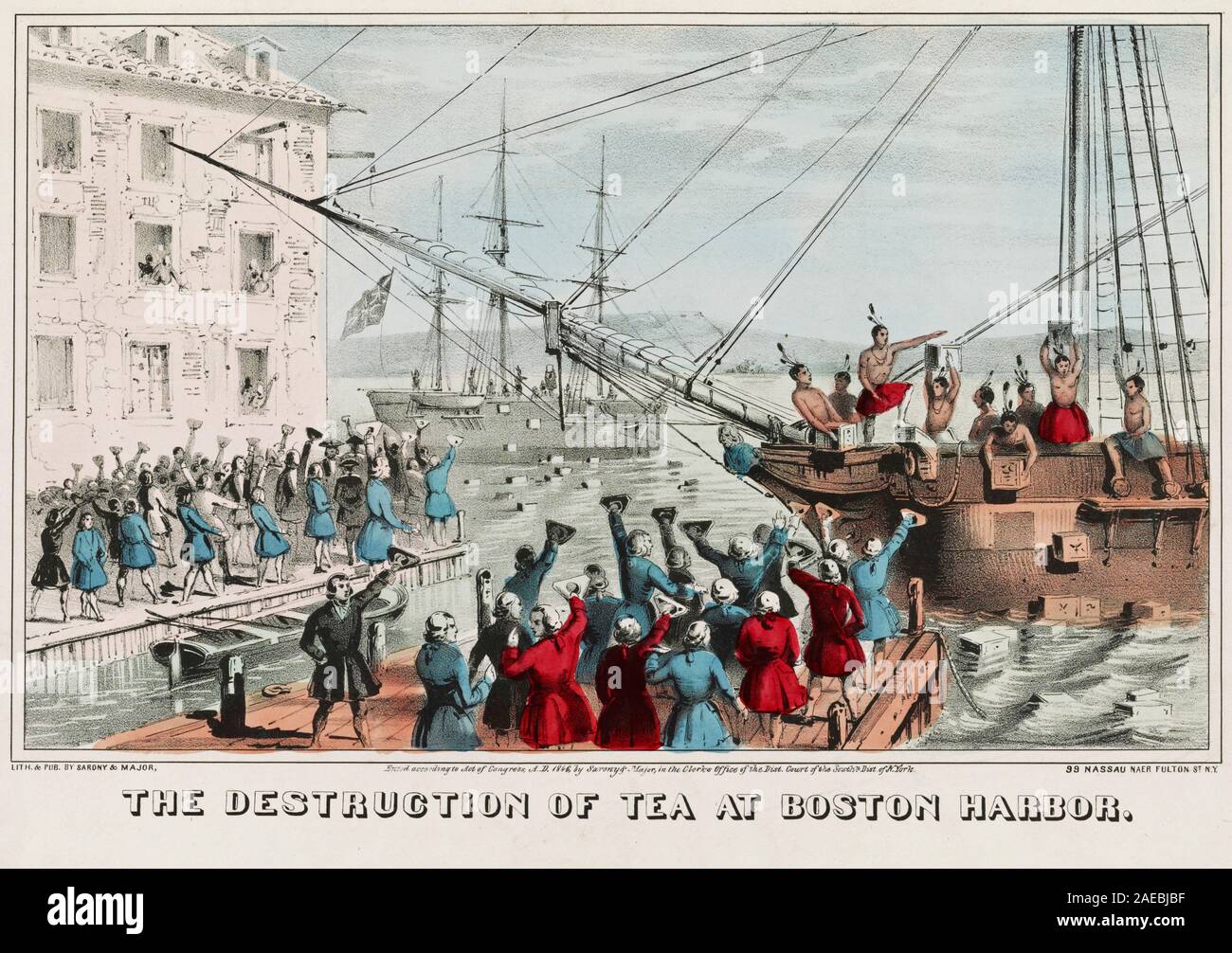

In the crisp autumn of 1773, a single act of defiance on the bustling docks of Boston transformed a growing crisis into an unstoppable storm—when colonists dumped 342 chests of British East India Company tea into Boston Harbor, igniting a revolution. Known as The Boston Tea Party, this bold protest was not spontaneous chaos but a calculated, chemically laden statement against taxation without representation. Dressed as Mohawk Indians, an estimated 60 disguised patriots dumped 92 tons of tea—valued at over £10,000 in today’s currency—shattering British authority and igniting a colonial fire that transcended mere cargo destruction.

The event marked a pivotal turning point, where economic grievance evolved into outright rebellion, setting the舞台 for the American War of Independence.

Three years earlier, the passage of the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, had set the stage. Britain, burdened by debt from the French and Indian War, sought to rescue the financially faltering East India Company by granting it a monopoly on tea sales in the colonies.

The act allowed the company to bypass colonial merchants and sell tea directly to American ports at a lower maritime tax, undercutting local traders but retaining a symbolic tax stamp marked “tea for America.” Though framed as a trade reform, colonists viewed the Tea Act as a violation of self-governance—“no taxation without representation”—fueling widespread outrage. As historian Gordon Wood notes, “The Tea Act was not about the price of tea. It was about power.”

On the night of December 16, 1773, Boston’s harbor became a theater of resistance.

Under cover of darkness, approximately 115 men, many members of the Sons of Liberty, assembled on three ships: the Dartmouth, the Beaver, and the Eleanor. Disguised in painted mohawk wigs and bear pelts, they worked in silence to remove 342 chests—each inscribed with company and royal crest marks—from the decks. “We are not only striking a blow against taxation,” one participant later wrote, “but against tyranny itself.” No shots were fired, and no civilians were harmed—an intentional choice to underscore moral urgency over violence.

As tea flowed into the harbor, estimates suggest over 90% of the cargo vanished within minutes.

While the act itself was remarkably coordinated, the identities behind the disguises remain partially obscured by history. Yet, key figures were instrumental. Samuel Adams, master strategist and architect of resistance in Massachusetts, had galvanized public sentiment through the Massachusetts Circular Letter and Committees of Correspondence.

Francis Wayland, a Boston merchant and patriot, later described the act as “a sacrament of liberty.” Though many participants risked execution, only two were formally charged—both acquitted amid progressive public sentiment. The British Parliament responded with the Coercive Acts (Intolerable Acts), banning self-governance in Massachusetts and sealing the colonies’ march toward full war.

The political fallout was immediate and severe. By mid-1774, the First Continental Congress convened to unify resistance, issuing a boycott of British goods and calling for reconciliation.

Yet the Tea Party had already destabilized the imperial order; the Crown saw colonists not as subjects but as insurgents mere hours before. British merchants, financially ruined, lobbied harshly for punitive measures they knew would provoke further defiance. Boston’s destruction transformed a local protest into a national crisis.

As historian Bernard Bailyn observed, “The destruction of the tea was not a riot—it was rhetoric made concrete, a refusal to be governed by power without consent.”

Culturally, the event became mythologized. The myth of seamless Mohawk disguises was partly romanticized—some accounts reveal makeshift costumes, not full regalia—yet the symbolic power endures. The term “tea party” itself, long associated with casual gatherings, takes on historical gravity when linked to rebellion.

The next year, colonists at Lexington and Concord would fire the first shots of war, directly tracing their resolve to Boston’s 1773 defiance. The Boston Tea Party was not merely an act of vandalism; it was a crystallized demand for voice, justice, and sovereignty—igniting a revolution that would reshape the world.

This event underscored a fundamental truth: revolutions rarely begin with grand speeches alone. They ignite in the dark, over stolen tea, by hands determined to say, “We govern ourselves.” Boston 1773 was the spark that couldn’t be contained, proving that the spirit of resistance is born not in noise, but in silent, defiant action.

The world would never look the same after that fateful night.

Related Post

Zayn Malik’s Spiritual Dimension: How Islamic Heritage Shapes His Artistic Journey

Promising Talent Dyani Redclay: Spearheading Indigenous Participation

The Shocking Truth Behind the Kindly Myers Leak: What Experts Reveal About the Privacy Breach That Ignited Controversy