Southern Colonies' Economic Engine: The Sugarcane, Tobacco, and Cash Crops That Built an Empire

Southern Colonies' Economic Engine: The Sugarcane, Tobacco, and Cash Crops That Built an Empire

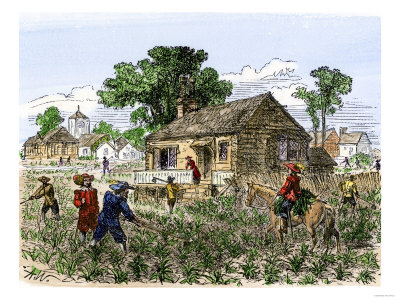

The Southern Colonies flourished not by accident—but by design, driven by a powerful triad of cash crops: tobacco, indigo, rice, and later, long cotton. These commodities formed the backbone of a regional economy deeply intertwined with global trade, slavery, and colonial enterprise. From Virginia’s tobacco fields to Georgia’s rice plantations, economic activity in the South was defined by large-scale agricultural production, export dependency, and the relentless expansion of plantation systems.

The foundation of Southern prosperity rested on cash crops uniquely suited to the region’s climate and soil. Tobacco, quick to emerge as a lucrative export, dominated early settlement in Virginia and Maryland. John Rolfe’s successful cultivation of sweet tobacco in the early 1600s transformed the colony’s fortunes, turning distant farms into engines of wealth.

By the mid-17th century, tobacco exports fueled immigration and commerce, establishing export networks that stretched from Jamestown to London’s dockyards. Tobacco’s economic grip was profound but volatile. Fluctuating prices and dependency on English markets meant colonists remained subject to imperial regulation, yet its profitability set a precedent: agriculture as a driver of colonial economy.

“Tobacco was more than a crop—it was the Southern Colonies’ financial lifeline,” notes historian Carol Berkin, emphasizing how its production structured labor systems and land use. Beyond tobacco, Southern economies diversified through region-specific crops. In the Carolinas, rice became a dominant commodity, particularly on the coastal plantations of South Carolina’s Lowcountry.

The intricate engineering of tidal rice fields—flooded paddies and sophisticated irrigation—demonstrated colonial agronomic expertise. Irish and enslaved Africans, drawn from diverse technical backgrounds, mastered these systems, enabling rice to become a staple export that enriched both planters and colonial trade coffers. Long before cotton rose to dominance, South Carolina and Georgia cultivated indigo—a dye crop prized in Europe for its vibrant blue hue.

Revived and scaled under merchant-led initiatives in the 1740s, indigo rapidly became a secondary but vital economic force. John Rutledge and other colonial leaders supported indigo production through trade protections and marketing networks, turning Charleston a major indigo hub. By the 1770s, indigo exports helped diversify Southern wealth beyond tobacco.

The emergence of long-staple cotton in the late 18th century marked a pivotal shift. Though invented earlier, cotton’s true economic potential ignited with Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (1793), dramatically increasing processing efficiency. Southern planters—especially inanterior Virginia, the Carolinas, and later Mississippi—rapidly expanded cotton acreage.

By 1860, cotton accounted for over half of the world’s supply, cementing the South’s role in the global textile economy. As historian David Brion Davis observed, cotton “transformed the Southern economy from one based on diversified crops to one overwhelmingly dependent on a single cash crop.” This agricultural focus was inseparable from the institution of slavery. The labor-intensive nature of tobacco curing, rice field management, indigo processing, and cotton harvesting relied on sustained, coerced labor.

Enslaved Africans and their descendants formed the backbone of plantation life, performing grueling work under harsh conditions. The economic model of the South was thus explicitly slave-dependent—a fact underscored by meanings far beyond mere production. “Slavery was not an accident of Southern economics; it was its foundation,” asserts scholars like Stephanie Jones-Rogers, who emphasize how wealth generated by cash crops was built on unfreedom.

Breaking down the economic activities reveals distinct regional specializations. In Virginia and Maryland: - Tobacco cultivation drove colonial income. - Small-scale wheat farming appeared but couldn’t compete with export demand.

In South Carolina and Georgia: - Rice required specialized knowledge and infrastructure; indigo expanded later as a high-value export. In frontier Southern regions like parts of Virginia and Georgia: - Mixed farming supplemented large plantations, growing corn, peas, and livestock for local markets. Agriculture’s reach extended beyond fields—shaping ports, shipping, banking, and retail.

Shipyards in Charleston and Baltimore flourished shipping tobacco, rice, and cotton across the Atlantic and into domestic markets. Insurance branches in Philadelphia and London underwrote the volatile grain trade, while wealthy planters invested in London stock, linking Southern wealth to global finance. While cash crops brought immense profit, they also imparted structural vulnerabilities.

Overreliance on single commodities left colonial economies susceptible to market shifts and British mercantilist policies that restricted trade. Yet, despite these risks, Southern agriculture remained resilient, adapting to new markets, technologies, and labor systems. The legacy of the Southern Colonies’ economic activities endures in modern agricultural practices and enduring debates about labor, equity, and sustainability.

The crop-driven model established between the Chesapeake and the Gulf exemplified both the ingenuity and inequity of pre-Civil War America—a testament to how economic ambition, rooted in land and labor, shaped a nation. In the end, the story of southern economic activity is one of convergence: crops shaped by soil and climate converged with human systems—of slavery, trade, and capital—to forge a region that powered colonial empires and defined an era of American history.

Related Post

Mike Majlak Age Girlfriend and Net Worth of The Famous YouTuber

<Are James Garner And Jennifer Garner Related? A PLOT THREAD OF FAMILY, FANDOM, AND FORTUNE

Is This The Darkest Secret of the Internet? Anon Ib Archives Expose a Hidden Digital Abyss