Software vs Hardware: The Battleground of Performance, Flexibility, and Future Tech

Software vs Hardware: The Battleground of Performance, Flexibility, and Future Tech

In the ever-evolving landscape of computing, the timeless debate between software and hardware shapes how we design, deploy, and interact with digital systems—from everyday smartphones to cutting-edge AI infrastructure. While hardware provides the foundational physical machinery, software acts as the dynamic layer that animates and controls that machinery, transforming raw circuits into intelligent functionality. Understanding their fundamental differences, strengths, and real-world applications reveals not just a technical contrast, but a strategic divide that influences innovation, cost, and scalability across industries.

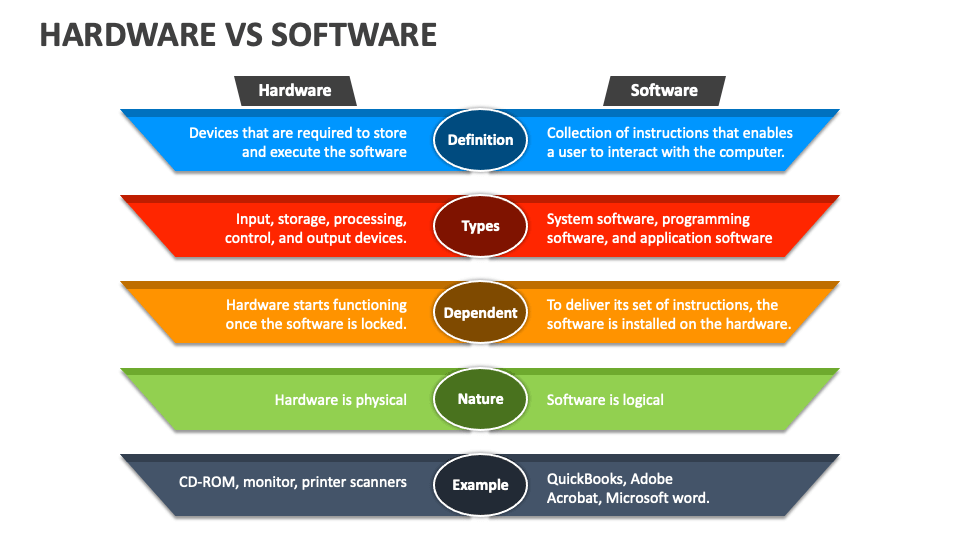

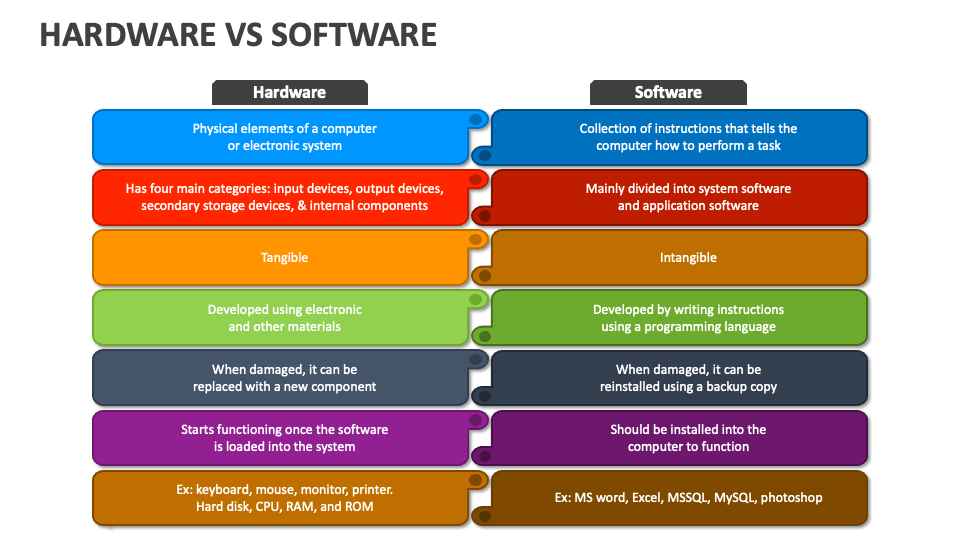

At its core, hardware—encompassing processors, memory, storage, and peripheral devices—forms the tangible platform upon which computing operates. It is bound by physical constraints: performance bottlenecks, fixed architectures, and diminishing returns as components grow smaller. In contrast, software—ranging from operating systems and firmware to complex applications—offers adaptability, programmability, and rapid evolution without altering silicon.

This fundamental distinction drives divergent paths in speed, deployment, and optimization. As industry experts note, “Hardware sets the ceiling; software defines the ceiling climb.” When evaluating use cases, the choice between software or hardware is rarely binary but rather a calculated balance informed by performance needs, budget, and long-term flexibility.

The Physical Foundation: Hardware Defined

Hardware represents the immutable, physical infrastructure of computing—integrated circuits, microprocessors, and memory modules that process and store data.Unlike software, which can be updated remotely and iteratively, hardware implies permanent alteration; changing processing power or storage capacity typically demands physical upgrades. Key hardware components include:

• Central Processing Units (CPUs): The brain of a computer, responsible for executing instructions. Modern CPUs, such as Intel’s Core i9 or AMD’s Ryzen series, integrate billions of transistors on a single die, enabling complex calculations at lightning speed.

• Random Access Memory (RAM): Volatile storage that temporarily holds data and programs currently in use, directly influencing system responsiveness.

High-speed DDR5 RAM, for example, supports multi-threaded workloads critical in gaming and data analytics.

• Storage Systems: From traditional hard disk drives (HDDs) to solid-state drives (SSDs), storage determines data retrieval speed—the difference between slow boot times and near-instantaneous application launch.

• Input/Output Devices: Keyboards, touchscreens, sensors, and actuators bridge human interaction with digital systems, essential for user experience but often overlooked as core components.

Hardware’s permanence imposes limits. Once deployed, upgrading hardware may involve expensive replacements, such as installing a faster SSD or swapping a thermal plate for better cooling. For enterprises managing large-scale operations, hardware constraints affect scalability and uptime—real-world examples include data centers where physical server racks cannot be replaced overnight, necessitating phased upgrades and careful resource planning.Similarly, embedded systems in industrial robots or medical devices depend on reliable, durable hardware with minimal failure risk, where software-only solutions fall short.

Software: The Infinite Layer of Intelligence

Software—the intangible assembly of programs, algorithms, and interfaces—transforms hardware potential into utility. Unlike hardware, which is constrained by silicon, software evolves through updates, patches, and algorithmic innovation.Key aspects include:

• Operating Systems: The backbone layer that manages hardware resources, enabling applications to run efficiently. Windows, Linux, and macOS exemplify how software orchestrates diverse hardware into cohesive user experiences.

• Applications and Algorithms: From spreadsheets to machine learning frameworks, software delivers functionality tailored to human needs—process automation, data visualization, and real-time analytics.

• Middleware and APIs: Enable disparate systems to communicate, creating integrated ecosystems across devices and platforms.

• Firmware: Slightly bridging hardware and software, firmware instructs hardware behavior—such as BIOS/UEFI managing boot processes or IoT device controls—without being full software.

Software’s adaptability shines in dynamic environments. Cloud-based platforms, for example, leverage elastic software to scale computing power on demand—deploying virtual machines and containerized services—without physical hardware changes.In artificial intelligence, software frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch harness underpowered hardware through intelligent optimization, demonstrating that software can maximize performance where hardware constraints exist. Moreover, software updates breathe new life into legacy hardware: a 10-year-old smartphone remains viable for casual use with upgraded mobile OS versions, extending its lifecycle far beyond hardware durability.

Yet software depends on hardware to function.

Without the proper silicon—fast memory, capable CPUs, or specialized accelerators like GPUs—even the most sophisticated software remains idle. This mutual reliance defines their symbiotic relationship: software expands the effective capabilities of hardware, while hardware provides the necessary platform for software to operate.

Performance, Scalability, and Cost: A Strategic Divide

In high-stakes domains such as gaming, scientific simulation, and AI training, the choice between software and hardware defines performance boundaries. High-end gaming consoles like the PlayStation 5 or AMD-based PCs feature custom RDNA2 GPUs paired with ultra-fast SSDs—hardware engineered specifically to deliver 4K real-time rendering.Here, software—optimized drivers and game engines—takes full advantage of silicon’s peak capabilities. Software alone cannot transcend the limits of frame rate or resolution without compatible hardware.

Scalability reveals another dimension.

In data centers, cloud providers deploy software-defined architectures—leveraging flexible virtualization and container orchestration—to dynamically allocate hardware resources. This software-driven elasticity allows companies to scale workloads during peak demand without overspending on underutilized physical infrastructure. Conversely, in embedded systems—such as automotive ECUs or industrial automation controllers—hardware durability and reliability outweigh software flexibility.

Replacing a faulty sensor-equipped hardware module is often more practical than overhauling software to support legacy constraints.

Cost considerations further differentiate the two. High-performance hardware—such as server-grade processors with large cache and multi-core architectures—represents significant upfront investment.

Meanwhile, software often offers lower entry barriers: open-source tools, subscription-based SaaS models, and low-code platforms enable broader access. Yet, in advanced sectors like quantum computing or AI inference, the total cost blends both: custom silicon paired with high-precision software algorithms achieves breakthrough performance unattainable through software alone.

Compatibility and Ecosystem: The Interdependency Factor

No distinction between software and hardware exists in isolation—both shape and depend on each other within broader technological ecosystems.Enterprise environments demand consistency: ERP systems require aligned hardware (servers, workstations) and software (custom ERP suites) to ensure data integrity and operations continuity. In consumer tech, user experience hinges on seamless integration—iPad software optimized for A-series chips, or Android apps designed around ARM-based processors.

Application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) exemplify this synergy.

Custom-built for narrow tasks—like cryptocurrency miners or neural processing units (NPUs)—ASICs deliver unmatched efficiency only when supported by tailored software stacks. Similarly, graphics processing units (GPUs) from AMD and NVIDIA achieve peak performance in gaming and AI only when paired with optimized drivers and APIs that drive parallel computation.

Even in mobile ecosystems, software and hardware converge.

Apple’s A-series chips are purpose-built to accelerate iOS and machine learning workloads, creating a performance loop where hardware enables richer software experiences, which in turn drive demand for increasingly sophisticated hardware. This tight coupling, critics warn, can lock users into vendor ecosystems, complicating choice and interoperability—a tension underscoring software and hardware’s role as strategic levers in digital competition.

Navigating the Future: When to Choose Software, When Hardware

The software versus hardware debate is not about which is superior, but about alignment—matching capabilities to purpose.For lightweight tasks and user accessibility, software often delivers maximum value: a basic Windows laptop with mid-tier hardware competes effectively across productivity and casual use. For resource-intensive workloads—deep learning, real-time analytics, high-end rendering—hardware investment becomes indispensable, especially when software alone cannot close performance gaps.

Industry experts emphasize strategic balance: companies improving efficiency benefit from modular upgrades—software optimization to extend hardware life or hardware acceleration to boost software speed.

In AI, hybrid approaches prevail; TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) accelerate training, but software frameworks like PyTorch shape how efficiently models run.

Sustainability trends also tilt the scale. Extended hardware lifespans—via adaptive software and firmware—reduce e-waste, while energy-efficient hardware paired with performance-optimized software lowers long-term carbon footprints.

Innovation flourishes where software and hardware evolve in tandem, each extending the other’s potential.

In an age defined by rapid technological change, understanding the interplay between software and hardware empowers informed decisions—whether designing scalable data systems, modernizing legacy infrastructure, or pioneering next-generation computing. Their dynamic relationship charts the course from silicon to intelligence, proving that true progress emerges not from choosing one over the other, but from mastering their symbiosis.

In essence, software and hardware are both architects of the digital world—each limiting, enabling, and redefining the next leap forward.

Related Post

Dive into Learning: The Essential Guide to Daily Learning That Powers Growth

Is Perry Ellis Shoes a Smart Investment? A Deep Dive into Comfort, Style, and Value

Jawaban Tebak Gambar Level 14: Decoding the Visual Puzzle’s Hidden Layers and Hidden Logic

Kikoo Sushi’s Guide to All-You-Can-Eat Sushi: How to Get Maximum Flavor for Every Yen