Single Replacement: The Chemical Power That Drives Elemental Transformation

Single Replacement: The Chemical Power That Drives Elemental Transformation

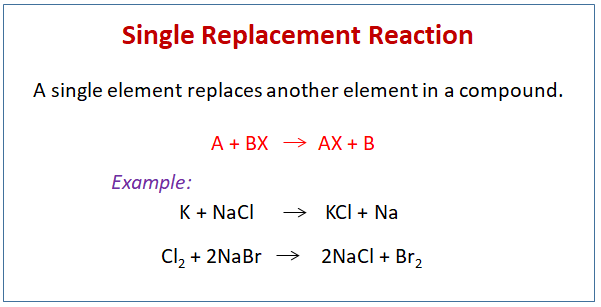

In the heart of chemistry lies a foundational reaction so powerful it shapes the transformation of matter at the atomic level: single replacement, a cornerstone of substitution reactions where one element displaces another within a chemical compound. Known formally as Single Replacement Definition Chemistry, this process epitomizes nature’s elegant mechanism for restructuring elements under the right conditions. From the bubbling cauldrons of ancient alchemy to the high-precision reactions in modern laboratories, single replacement reactions enable the dynamic reorganization of atomic identities—replacing one element with another in a compound, often releasing energy and altering physical and chemical properties.

This article explores the precise mechanics, wide-ranging applications, and enduring significance of single replacement as a defining concept in chemical reactivity.

Core Principles of Single Replacement Reactions

At its essence, single replacement chemistry follows a straightforward yet profound principle: when a more reactive metal encounters a less reactive metal within a compound, the more reactive metal displaces the less reactive one, forming a new metal compound and a free element. The generic form is often expressed as: M(s) + X2(aq) → MX(s) + X(s) where M represents a metal above hydrogen in the reactivity series, and X2 denotes a halogen or a more electropositive metal in solution.This reaction hinges on electrochemical principles: the difference in standard reduction potentials between the involved elements determines whether displacement is energetically favorable. “The driving force is the lower energy state,” explains chemist Dr. Elena Torres of the National Institute of Chemistry.

“A metal higher in the reactivity series reduces its own ions more aggressively, effectively ‘pulling’ a metal from compounds it could displace.” This hierarchical order—especially vital with metals—dictates whether a reaction proceeds. For example, zinc can displace silver from silver chloride, but not copper, due to zinc’s greater electron-donating capability. The displacement process is not merely theoretical; it follows predictable patterns defined by both empirical observation and quantitative electrochemistry.

The premium reactivity series ranks metals by their tendency to lose electrons, and it serves as the primary guide for predicting viable substitutions. Compounds such as metal halides, sulfides, and oxides become reactive intermediaries when exposed to suitable replacing agents.

Key steps in any single replacement reaction involve: • Identification of the reactivity order for all elements involved • Assessment of ion reduction potentials to determine feasibility • Monitoring changes in physical state—often liberation of a free metal or gas • Validation through spectroscopic or gravimetric analysis

These sequences ensure reaction specificity and safety, especially in industrial settings where unintended side reactions can pose hazards or waste resources.Real-World Examples and Practical Applications

Single replacement chemistry permeates both natural phenomena and engineered technology. Consider the alloying of metals—a process centuries old but grounded in modern chemical understanding. When zinc is added to molten copper, zinc oxidizes while displacing copper ions, forming metallic zinc and separating pure copper: Zn(s) + Cu²⁺(aq) → Zn²⁺(aq) + Cu(s) This reaction, simple yet transformative, illustrates how substitution underpins metallurgical advances and material science.In halogen displacement, chlorine displaces bromine from calcium bromide—yet not iodide, because chlorine is less reactive than bromine—and silver ions are displaced by copper, forming coupled precipitates: Cl₂(aq) + CaBr₂(aq) → CaCl₂(aq) + CuBr(s) + AgCl(s) Such displacement reactions form the basis of qualitative analysis in environmental and forensic chemistry, allowing scientists to detect metal ions by observing precipitate colors and solubilities. Farmers and industrial chemists alike exploit redox-driven displacement in wastewater treatment, where reducing agents remove heavy metal contaminants by converting toxic ions like chromium(VI) into less harmful metallic states. This principle extends to electroplating, where a target metal is coated onto substrates by displacing ions from solution—gold onto copper, for instance—enabling precision finishes in electronics and jewelry.

Environmental chemistry also reveals single replacement in action: limestone deposited underground through slow calcium carbonate accumulation can displace secondary minerals in reactive aquifers, altering groundwater into mineral-rich or corrosive forms. These natural cycles underscore displacement as a process not confined to labs but woven into Earth’s elemental Theater.

Industrial processes rely on carefully controlled single replacements: - Chlor-alkali eletrolysis uses chloride ions to produce chlorine and deposits reactive metals at electrodes - Solvent extraction in rare earth mining employs sequential replacements to isolate critical elements - Corrosion inhibition leverages displacement to form protective oxide layers on base metals

Each application demonstrates the reaction’s versatility and precision under optimized thermodynamic and kinetic control.Electrochemical Foundations and Quantitative Insights

Underpinning the single replacement phenomenon is a deep electrochemical framework. The potential difference between two metals’ standard reduction values determines whether electrons will flow from one to the other. For example, zinc (+0.76 V) has a higher reduction potential than copper (+0.34 V), meaning zinc corners out copper in solution: Zn²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Zn(s), E° = −0.76 V Cu²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Cu(s), E° = +0.34 V Net: Zn(s) + Cu²⁺(aq) → Zn²⁺(aq) + Cu(s), ΔE° = +1.10 V (spontaneous) These values, measured under standard conditions, form the Nernst table—critical for engineers and chemists designing batteries, sensors, and protective coatings.The larger ΔE°, the greater the driving force for displacement and electrical energy generation. Additionally, Le Chatelier’s principle influences reaction yield: removing the newly formed element (e.g., evaporating Cu(s)) shifts equilibrium forward, knitting single replacement toward completion. In industrial electrolysis cells, temperature, agitation, and electrode surface area further modulate reaction speed and efficiency.

While kinetics often favor faster reactions, thermodynamic favorability remains the ultimate gatekeeper—ensuring that only energetically viable substitutions occur without deleterious side effects or material degradation.

< Everything from ancient metal extraction to modern semiconductor fabrication depends on single replacement’s elegant simplicity. As chemical reactivity evolves through new catalysts and computational modeling, this foundational reaction remains central—not merely as a textbook curiosity, but as a living, adaptive process shaping science and society. Understanding and harnessing single replacement chemistry empowers innovation across disciplines, proving once again that the displacement of elements is not just a reaction, but a catalyst for progress.

Related Post

How Smart Cities Are Transforming Urban Life One Innovation at a Time

Did Luke Combs Have A Brother? The Truth Behind The Combs Family’s Hidden Roots

The Empowerment Powerhouse: How Empire TV’s Hakeem Reshapes Modern Storytelling