Severe Sepsis A Comprehensive Guide: Understanding the Silent Killer Beneath Critical Illness

Severe Sepsis A Comprehensive Guide: Understanding the Silent Killer Beneath Critical Illness

Severe sepsis is a life-threatening condition arising from the body’s overwhelming response to infection, triggering systemic inflammation that can rapidly progress to organ failure and death. Often misunderstood in its early stages, it represents a critical intersection between infection control, immune dysregulation, and intensive medical intervention. This guide delivers a deep dive into the diagnosis, risk factors, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, management protocols, and long-term outcomes of severe sepsis—offering clarity for healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers navigating one of medicine’s most urgent challenges.

Defined by a cascade of hemodynamic and metabolic disturbances in response to infection, severe sepsis-inducing changes extend beyond mere infection to systemic dysfunction. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identifies sepsis when life-threatening organ impairment accompanies confirmed or suspected sepsis, with severe sepsis marking this progression. Recognizing this distinction is vital: sepsis is clinical; severe sepsis is critical.

The Chain of Events: From Infection to Systemic Collapse

At its core, severe sepsis begins with an infection—typically bacterial, though viral or fungal pathogens can also trigger the cascade.Pathogens invade tissues, prompting the immune system to release signaling molecules such as cytokines and endotoxins. This immune surge causes widespread vascular leakage, capillary dysfunction, and microvascular thrombosis, impairing blood flow to vital organs.

Key pathological features include:

- Hyperinflammation driven by cytokine storms (e.g., TNF-alpha, IL-6), disrupting normal clotting pathways

- Endothelial damage increasing vascular permeability and promoting disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Myocardial depression lowering cardiac output

- Cellular energy failure due to mitochondrial dysfunction

- Mitochondrial impairment leading to tissue hypoxia despite adequate oxygen delivery

Who Is at Risk? Identifying Populations Vulnerable to Severe Sepsis

Certain groups face heightened susceptibility to severe sepsis. Older adults over 65 are at increased risk due to age-related declines in immune function and comorbidities.Patients with chronic conditions—including diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and immunosuppression (from autoimmune disease treatments or HIV)—face compromised defenses that allow infections to escalate quickly.ديك

Among hospital populations, intensive care unit (ICU) patients are particularly vulnerable, with rates of severe sepsis reaching up to 30% among those with bloodstream or respiratory infections. Pediatric populations, while less commonly affected, face unique challenges: neonatal sepsis presents subtly, often mimicking sepsis of uncertain origin, delaying diagnosis. Immunocompromised individuals, including cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or transplant recipients, lack robust immune responses, enabling unchecked pathogen spread.

Clinical Features: From Symptoms to Organ Dysfunction

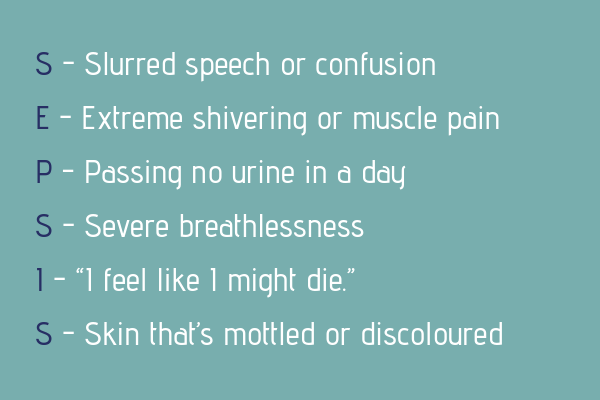

Recognizing severe sepsis demands awareness of its evolving clinical presentation.Initial symptoms—fever, elevated heart rate, rapid breathing, confusion, or low blood pressure—overlap with common infections, complicating early detection. As the condition advances, organ-specific failures emerge: - Respiratory failure: Hypoxemia unresponsive to oxygen supplementation, often progressing to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) - Renal failure: Elevated creatinine, oliguria, or fluid overload despite standard management - Altered mental status: Delirium or coma from cerebral hypoperfusion or cytokine effects - Metabolic disturbances: Hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, or electrolyte imbalances indicating tissue hypoxia The Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria, though historically used, are increasingly supplemented by organ-specific scores such as the SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) or qSOFA (quick SOFA), designed to flag patients at higher risk of mortality.

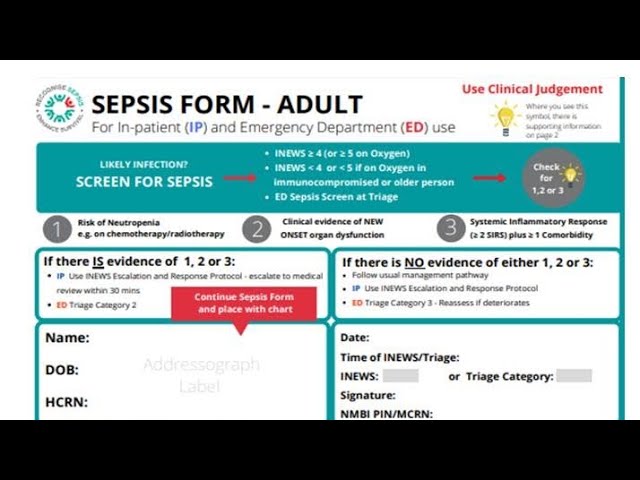

Diagnosis: Timely Recognition Is Life-Saving

Diagnosing severe sepsis hinges on rapid identification of infection *and* organ dysfunction.Clinicians use a combination of biomarkers and clinical assessments: - Blood cultures, lactate levels (>2 mmol/L indicating tissue hypoxia), and inflammatory markers (procalcitonin, C-reactive protein) support the diagnosis - Continuous monitoring of vital signs, urine output, and mental status enhances early detection - Identifying the source—whether urinary tract, pneumonia, intra-abdominal infection—guides targeted therapy

“A delay of more than two hours in recognizing severe sepsis kills thousands each year—timeliness is the difference between recovery and failure,”

says Dr. Elena Torres, critical care specialist at Mercy General Hospital. Her insight underscores the necessity of vigilance in emergency and ICU settings.Standard Management: A Protocol for Survival

The management of severe sepsis follows a time-sensitive, evidence-based approach centered on three pillars: early recognition, rapid intervention, and organ support.Immediate intervention begins with identifying and eliminating the source of infection using broad-spectrum antibiotics within the first six hours—a cornerstone endorsed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Concurrently, aggressive fluid resuscitation with crystalloids restores intravascular volume and perfusion.

For patients with persistent hypotension, vasopressors such as norepinephrine are administered to maintain mean arterial pressure above 65 mmHg.

Critical care support includes:

- Mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure, guided by lung-protective strategies to prevent ventilator-induced injury

- Renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury refractory to medical management

- Hypothermia management in selected cases, though strict protocols govern timing and duration

- Anticoagulation for DIC in patients meeting criteria, balancing bleeding risk with thrombotic danger

Emerging therapies—including recombinant activated protein C and immunomodulatory agents—remain under investigation, with limited adoption due to inconsistent trial outcomes.

Antimicrobial Stewardship and Source Control

The judicious use of antibiotics is fundamental to effective sepsis management. Empiric therapy targets likely pathogens but must be narrowed promptly based on culture results to minimize resistance. Simultaneously, surgical drainage of abscesses, removal of infected devices, or drainage of empyema addresses the infection’s origin, accelerating clinical response.Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes: Beyond Survival

Despite advances in critical care, severe sepsis remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Studies report a 20–30% mortality rate at 28 days, rising above 50% in high-risk subgroups. Survivors often endure lasting organ impairments: post-sepsis syndrome manifests as muscle wasting, cognitive disability, cardiovascular deterioration, and chronic fatigue.Rehabilitation plays a crucial role in recovery. Multidisciplinary programs combining physical therapy, occupational support, and psychological care improve long-term functional status. Patient education about infection prevention—especially for those with indwelling devices—reduces recurrence risk.

The broader healthcare impact is profound: severe sepsis accounts for millions of hospital days annually and strains healthcare systems globally.

Patient-centered care, early discharge planning, and population-level surveillance remain vital to improving outcomes.

Severe sepsis is a complex interplay of infection, immune overreaction, and systemic failure—demanding swift identification and coordinated, life-saving intervention. From recognizing early warning signs to managing organ dysfunction and supporting long-term recovery, every phase requires expert coordination. As medical science advances, so too do the tools and protocols to transform critical sepsis into treatable illness.Awareness, timely care, and a multidisciplinary approach remain the most powerful weapons against this unseen threat.

Related Post

A Father’s Silent Language: How Hangman Phrases Shape Language, Culture, and Mind