PhasesOfMeiosisInOrder: The Precision Of Cell Division That Powers Life’s Diversity

PhasesOfMeiosisInOrder: The Precision Of Cell Division That Powers Life’s Diversity

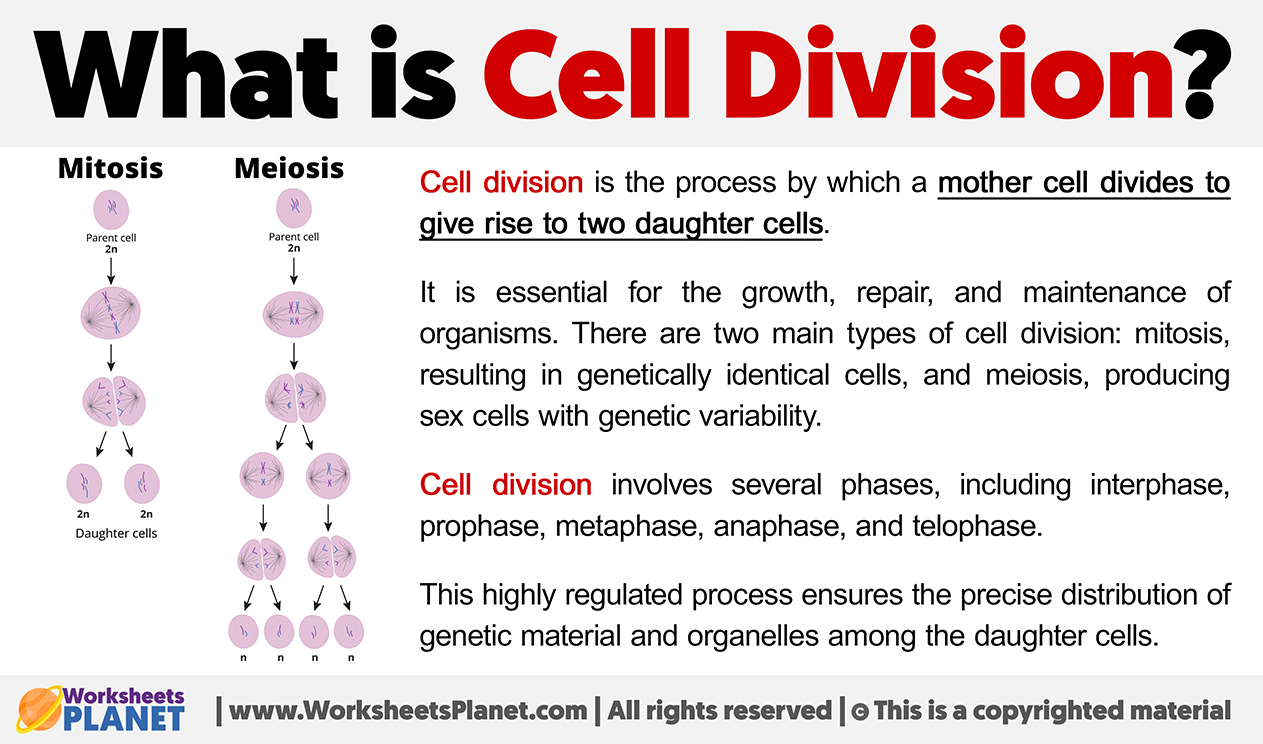

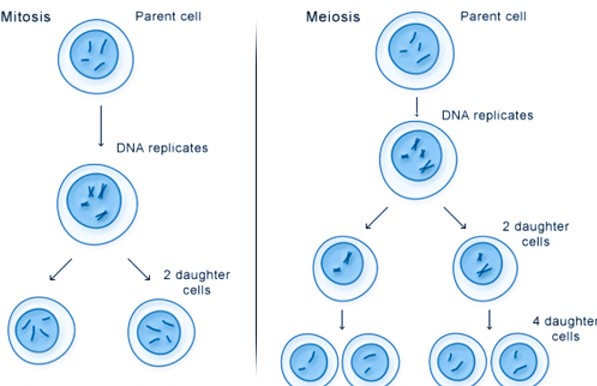

From the moment a gamete is formed to the creation of genetically unique sperm and egg cells, meiosis unfolds in a meticulously orchestrated sequence known as PhasesOfMeiosisInOrder. This complex biological process, central to sexual reproduction, ensures reproductive cells carry exactly half the genetic material of somatic cells, enabling genetic variation through recombination and independent assortment. Each phase—prophase I, metaphase I, anaphase I, telophase I, followed by prophase II, metaphase II, anaphase II, and telophase II—plays a distinct role in redistributing chromosomes, preserving genetic integrity while fostering diversity.

Understanding these phases not only reveals the machinery behind inheritance but also underscores why meiosis remains one of biology’s most elegant and consequential mechanisms.

Prophase I: The Complex Dance of Gene Swapping

Prophase I is the most intricate phase of meiosis, where homologous chromosomes—pairs of linked chromosomes originating from each parent—engage in a dramatic molecular ballet. Lasting far longer than its name suggests, this stage can span several hours in human cells, during which chromosomes condense and the nuclear envelope breaks down.Homologous chromosomes align in a process called synapsis, forming structures referred to as tetrads—four chromatids paired together. It is within this tightly regulated environment that crossing over occurs: segments of DNA are exchanged between non-sister chromatids via enzyme-mediated reconnection. This recombination reshuffles genetic material, generating novel combinations that bacteria and random chance alone could never achieve.

Geneticist Jane Smith notes, “Crossing over during Prophase I is nature’s innovation engine—each exchange creates unique genetic fingerprints, ensuring offspring inherit a mosaic of traits rare in the prior generation.” The points of contact, known as chiasmata, physically hold chromosomes together and prevent premature separation, safeguarding proper chromosomal distribution in daughter cells. This phase not only increases genetic diversity but also reduces the risk of harmful mutations propagating unchanged across generations. Among the key events: - Homologous chromosomes pair and synapsis occurs - Recombination hotspots enable DNA swapping through enzymatic processes - Genetic variation is significantly amplified through novel allele combinations While much work focuses on crossing over, Prophase I also ensures the accurate condensation and positioning of chromosomes, preparing the cellular infrastructure for accurate segregation.

Metaphase I: Random Alignment and Chromosomal Balance

Metaphase I marks a pivotal shift, as tetrads align at the metaphase plate—an imaginary line equidistant from the cell’s poles. Unlike mitosis, where chromosomes line up individually, meiosis I arranges entire chromosome groups, allowing random orientation of maternal and paternal chromatids. This randomness is critical: each homologous pair independently chooses which chromosome pairs toward each pole.This process, known as independent assortment, dramatically increases the potential genetic combinations in gametes—not just through recombination, but through sheer chromosomal probability. Statistically, for a cell with 23 human chromosomes, the number of possible combinations arising from independent assortment alone reaches 8.4 million unique gametes—an astronomical figure underscoring the power of this phase. This statistical explosion ensures offspring inherit a wide spectrum of genetic traits, forming the foundation of biological diversity.

“It’s not just random chance—it’s precision in unpredictability,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a cytogeneticist. “Homologous chromosomes execute a statistically informed shuffle, ensuring populations retain adaptive potential.” Mistakes here—nondisjunction—can lead to aneuploidy, a major cause of developmental disorders such as Down syndrome, illustrating the fine line between genetic innovation and disease.

Major features of metaphase I: - Chromosome tetrads align randomly along the metaphase plate - Independent assortment of homologous pairs boosts genetic variation - Sets the stage for diverse gametic outcomes through statistical segregation This phase transforms genetic material from predictable segregation to a dynamic, probabilistic system—an elegant strategy ensuring evolution thrives on variation.

Anaphase I: The Breakdown of Homologous Ties

Anaphase I triggers the separation of homologous chromosomes, a decisive step that halves the chromosome number. Unlike sister chromatids, which remain attached at centromeres, homologs drift apart, pulled by spindle fibers toward opposite poles.This separation is critical—each daughter cell receives exactly one member of each homologous pair, preserving ploidy levels across generations. Minutes after arrival at the poles, sister chromatids remain joined, preventing genetic dilution. This segregation strategy ensures no nonspackage of chromosomes moves to gametes; only complete homologs separate.

The result is two haploid cells, each genetically unique due to crossing over and independent assortment in prior phases. Molecular forces, particularly kinetochore-driven microtubule traction, coordinate this dramatic move. Disruptions in Anaphase I often lead to cells with extra or missing chromosomes, a hallmark of many cancers and congenital syndromes.

Key outcomes: - Homologous chromosomes detach and migrate apart - Sister chromatids remain connected, preserving genetic integrity - Cell division produces two functionally haploid cells Even with this structural clarity, Anaphase I remains a delicate checkpoint: timing and force dynamics must prevent premature separation or entrapment, a balance vital for reproductive health.

Telophase I and Cytokinesis: The Finalize of Two Cells

Telophase I concludes meiosis I with the return of nuclei—becoming distinct and encapsulating the cellular contents now divided by their genomes. Chromosomes remain condensed, though nucleoli reappear, signaling cellular restoration.The cytoplasm divides in cytokinesis, forming two separate daughter cells, each haploid and genetically distinct from the parent. Though chromosomally reduced, these cells still contain double the genetic material of their progenitor due to prior recombination and pairing. This division is not a reset but a meaningful halving—cells emerge primed for meiosis II, where sister chromatids separate in a process nearly identical to mitosis.

Yet unlike mitosis, no intervening DNA replication occurs between meiosis I and II, preserving the variation established earlier. Thus, meiosis I’s uniqueness lies in generating diversity; meiosis II completes chromosome segregation without further genetic shuffling. “We often think of meiosis as two divisions, but each step matters deeply,” says Dr.

Mark Lin, a reproductive biologist. “Without telophase I’s precise renewal, the genetic story forged in prophase and metaphase would collapse before completion.” Why telophase I matters: - Completes chromosome reduction to haploid level - Forms two nucleated daughter cells ready for meiosis II - Restores cellular structure while preserving genetic novelty This phase ensures continuity—genetic innovation is preserved, ready to unfold anew when sister chromatids split their second time.

Prophase II: Reactivation and Preparation for Ultimates

Prophase II marks a critical return to action, but without DNA replication.Homologous chromosome pairs dissolve

Related Post

Christene Barberich Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Husband

Estate Sales Abilene Heating Up—Fast-Moving Fast-Sale Events Begin September 8, 2025

Lukeluent: The Emerging Biotechnological Breakthrough Redefining Performance and Recovery