Osmosis Decoded: Is It Passive or Active? The Science Behind Nature’s Transport Mechanism

Osmosis Decoded: Is It Passive or Active? The Science Behind Nature’s Transport Mechanism

Osmosis, the silent yet fundamental process driving cellular hydration and nutrient uptake, lies at the heart of biological systems—from plant cells to human kidney tubules. Yet a persistent question divides enthusiasts and professionals alike: is osmosis passive, activated by energy, or something more nuanced? At its core, osmosis is classically defined as a passive transport phenomenon, driven not by cellular energy but by concentration gradients.

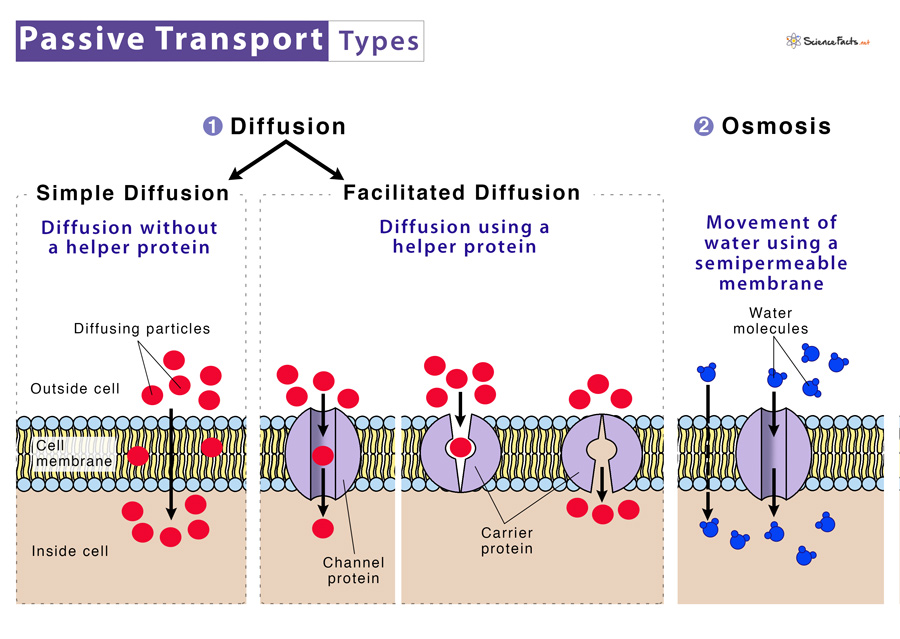

Understanding this distinction illuminates not only cellular physiology but also the design of life itself—from drought-resistant crops to advanced medical filtration systems. ### The Fundamentals of Osmosis: Passive Transport in a Dynamic Balance Osmosis refers specifically to the movement of water across a selectively permeable membrane from a region of lower solute concentration to higher solute concentration. This passive movement occurs without direct energy input, relying entirely on the thermodynamic gradient established by solute differences.

“Water flows down its chemical potential,” explains biophysicist Dr. Elena Rostova, “until equilibrium is reached—no ATP required.” Unlike active transport, which uses protein pumps (such as the sodium-potassium ATPase) to move molecules against concentration gradients, osmosis operates along the natural pull of diffusion. This passive mechanism plays a critical role in balancing internal environments.

In plant cells, osmosis draws water into vacuoles, maintaining turgor pressure essential for structural support. In animal cells, it regulates fluid exchange across membranes, preventing swelling or shrinkage. The process is equally vital in kidneys, where water reabsorption during urine formation depends on osmotic gradients established by solute transport.

At the molecular level, osmosis unfolds through the selective permeability of lipid bilayers. While most small, uncharged molecules like water easily pass through, larger solutes such as salts, sugars, or proteins remain confined to their initial compartment. “The membrane acts as a gatekeeper,” says cell biologist Dr.

Marcus Chen, “allowing water but not solutes—creating the perfect condition for passive flow.”

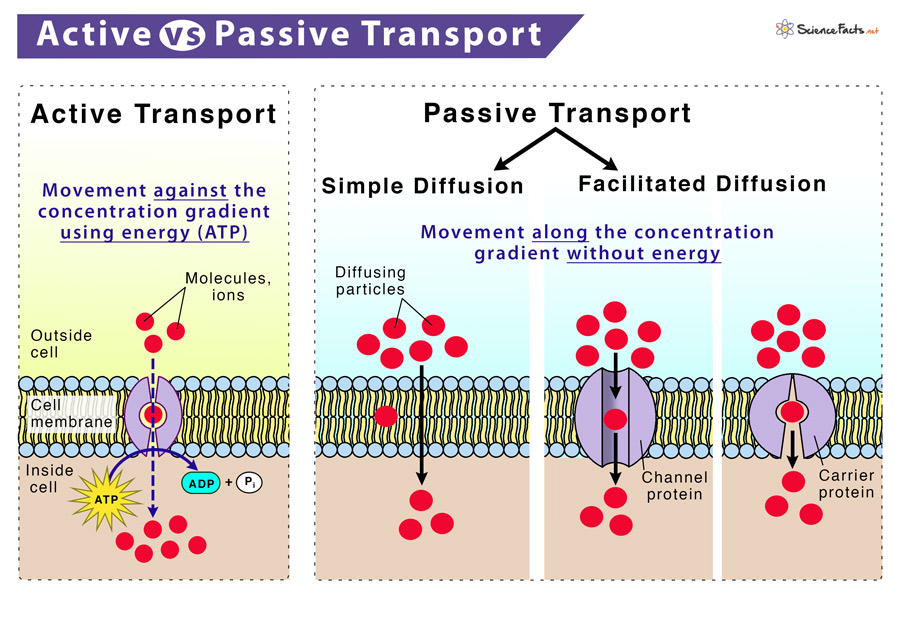

### Passive Transport Defined: The Role of Concentration Gradients Passive transport encompasses all movement substances down concentration gradients without direct energy expenditure—diffusion, facilitated diffusion, and osmosis all fall under this umbrella. Osmosis stands apart because it involves only water, a universal solvent, moving freely across membranes controlled solely by osmotic pressure. “What makes osmosis distinct,” clarifies biochemistry expert Dr.Lina Moreau, “is that while energy powers active transport, osmosis exploits existing energy differences.” This reliance on natural gradients ensures efficiency. For instance, in hypertonic solutions—where external solute concentration exceeds internal levels—water exits cells passively, a mechanism harnessed in plant adaptation to arid climates. Conversely, hypotonic environments drive water influx, critical for cell hydration yet requiring careful regulation to avoid rupture.

Osmosis thus exemplifies biological precision: a guaranteed, energy-efficient transport pathway that balances internal stability in fluctuating conditions.

Distinguishing Passive from Active Transport in Cellular Physiology

While osmosis remains resolutely passive, active transport mechanisms rely on ATP-dependent pumps to move ions or molecules against their concentration gradients. This active movement is essential for creating concentration differences themselves—such as the sodium gradient used to fuel neuronal firing or nutrient uptake in intestinal cells.To illustrate, consider the sodium-potassium pump, which expends energy to move three sodium ions out and two potassium ions in per cycle.

This active transport establishes the electrochemical gradient critical for nerve signaling. In contrast, when this gradient drives passive water movement through osmosis—say, into a cell in a hypotonic solution—the water flows freely, guided only by osmotic pressure, not metabolic energy.

Science communicator Dr. Amir El-Sayed emphasizes this difference: “Passive processes like osmosis are the unsung workhorses of cellular life—silent yet indispensable.

Active transport builds the gradients; passive transport maintains equilibrium.” This distinction clarifies why osmosis, unencumbered by energetic cost, operates continuously to sustain hydration at both micro and macro scales.

Real-World Applications and Biological Significance

Osmosis is far more than a textbook concept; its principles are embedded in cutting-edge science and everyday technology. In agriculture, osmotic understanding informs drought-tolerant mutations in crops—varieties that adjust internal solute levels to retain water under water scarcity.“Engineers are designing osmotic gates in plant cells to improve efficiency,” noted agronomist Dr. Fatima Al-Hassan, “making crops more resilient without extra irrigation.”

Related Post

Makayla Lysiak Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Boyfriend

Sunday Night Football Time Schedule and How to Watch It—Everything You Need to Know in 2024

Jay Ulloa Age Bio Wiki Height Net Worth Relationship 2023