Monroe Doctrine: The Unbroken Thread of America’s Defensive Foreign Policy Across Two Centuries

Monroe Doctrine: The Unbroken Thread of America’s Defensive Foreign Policy Across Two Centuries

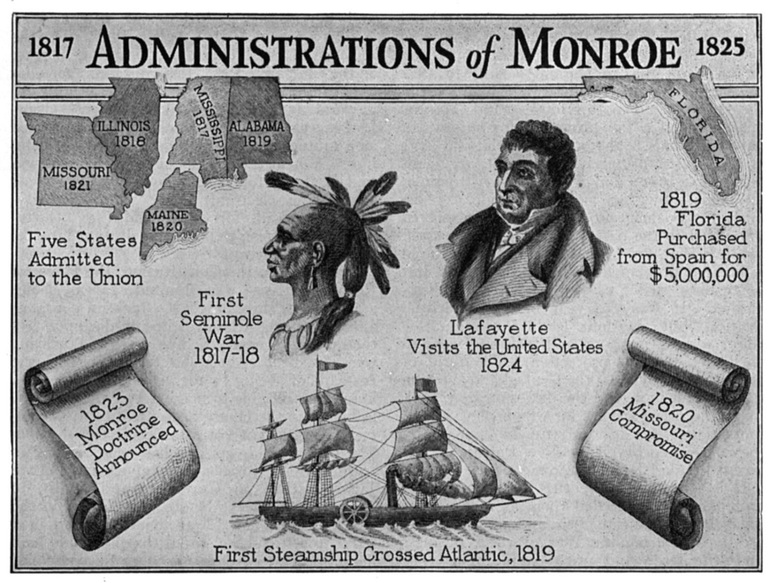

For over two centuries, the Monroe Doctrine has served as the cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy toward the Western Hemisphere—defining not only how the nation approached its southern neighbors but also setting enduring principles for its role on the global stage. Originally articulated in President James Monroe’s 1823 State of the Union address, the doctrine declared that European powers should “no longer interfere” in the affairs of independent American nations.

Far more than a simple warning, it established a hemispheric posture: the Americas would remain free from Old World colonial ambitions, and the U.S. would regard external intervention with suspicion and caution.

At its core, the Monroe Doctrine emerged from a confluence of strategic necessity and emerging American nationalism.

European empires, still reeling from revolutionary upheavals, sought to reclaim or establish colonies in Latin America, where newly independent states struggled to solidify sovereignty. Russia’s incursions into Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, combined with rumors of recolonization efforts backed by monarchies, alarmed American policymakers. Monroe’s message, drafted largely by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, condemned these schemes as incompatible with the era’s democratic ideals and hemispheric stability.

“From the American perspective, the Western Hemisphere is no longer open to discovery by or submission to external powers.” — James Monroe, 1823 State of the Union

The doctrine’s original formulation carried moral as well as strategic weight.

It asserted that the U.S. would not meddle in European affairs, reinforcing a policy of counterbalancing European imperialism while gently claiming regional leadership. But this principle of non-intervention also established a subtle but powerful precedent: the Americas would be America’s sphere, a zone of influence shaped by Washington’s quiet skepticism of foreign interference.

As historian Peter Chevrier notes, “The Monroe Doctrine was not just a rejection of colonialism—it was the first formal statement of a hemispheric consciousness that would guide American diplomacy for generations.”

The doctrine evolved significantly throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, adapting to shifting geopolitical realities while preserving its foundational concept: non-intervention by European powers. During the Spanish-American War (1898), President McKinley’s actions reflected a more assertive interpretation, using Monroe’s spirit to justify U.S. intervention in Cuba and Puerto Rico—steps that expanded America’s regional footprint but tested the doctrine’s original retreatist intent.

“America for Americans, Europe for Europeans”—a phrase echoing the doctrine’s original counter-imperial stance, still resonant in U.S.identity.

In the 20th century, the Roosevelt Corollary (1904) transformed Monroe Doctrine principles by asserting a proactive U.S. role: if Latin American nations were unable to maintain order, Washington would “intervene in the interests of stability.” While controversial, this expansion reaffirmed America’s self-appointed guardianship over the hemisphere, blending defensive intent with proactive policing. From military occupations in Haiti and Nicaragua to support for democratic movements during the Cold War, U.S.

policymakers repeatedly invoked Monroe Doctrine logic to justify actions ranging from economic influence to direct intervention.

Yet the doctrine’s most enduring legacy lies in its symbolic power. It institutionalized a narrative of hemispheric independence and American vigilance, shaping decades of foreign policy decisions. The policy balanced idealism—supporting self-determination—with realpolitik: the recognition that regional stability required active guardianship.

As former Secretary of State Colin Powell noted, the doctrine “reminds us that America’s role in the world includes not just global reach, but a historical responsibility to its neighbors.”

Today, the Monroe Doctrine endures not as a rigid doctrine of exclusion, but as a guiding philosophy embedded in modern American diplomacy. It informs responses to contemporary challenges—from Venezuelan political crises and Nicaraguan authoritarianism to Russian influence operations in the Caribbean. The principle that the Americas should be free from external domination remains a rhetorical and strategic anchor, particularly as great power competition intensifies.

As President Biden’s administration navigated sanctions on Venezuela and diplomatic engagements across Latin America, echoes of Monroe’s caution and assertiveness converged, demonstrating the doctrine’s continued relevance.

Monroe Doctrine’s strength lies in its flexibility. Though rooted in early 19th-century concerns, its core ideas—non-colonization, resistance to external intervention, and hemispheric solidarity—provide a framework for navigating 21st-century complexities. The doctrine teaches that meaningful foreign policy requires clarity of purpose: America’s role in the Americas is not merely strategic, but moral—a steadfast commitment to defending sovereignty and self-governance.

In plain terms: the Monroe Doctrine endures because it captures an enduring truth—no nation should hinder another’s rightful journey toward independence and stability.

From Monroe’s warning against European recolonization to modern diplomacy confronting geopolitical shifts, the doctrine remains proof that thoughtful, principled foreign policy endures. It is not about dominance, but about preserving a sphere where democratic aspirations, regional autonomy, and collective security can flourish—an evolving promise that continues to shape how the United States engages the Americas.

Related Post

Leak: The Hidden Engine Reshaping Global Data Flows and Corporate Surveillance

The Most Romantic Dinner in the Upper Midwest: Celebrating Fresh Fish from the Great Lakes

Indiana University Fall Break 2024 Dates Lock In—Don’t Wait, These Plans Need to Happen Fast

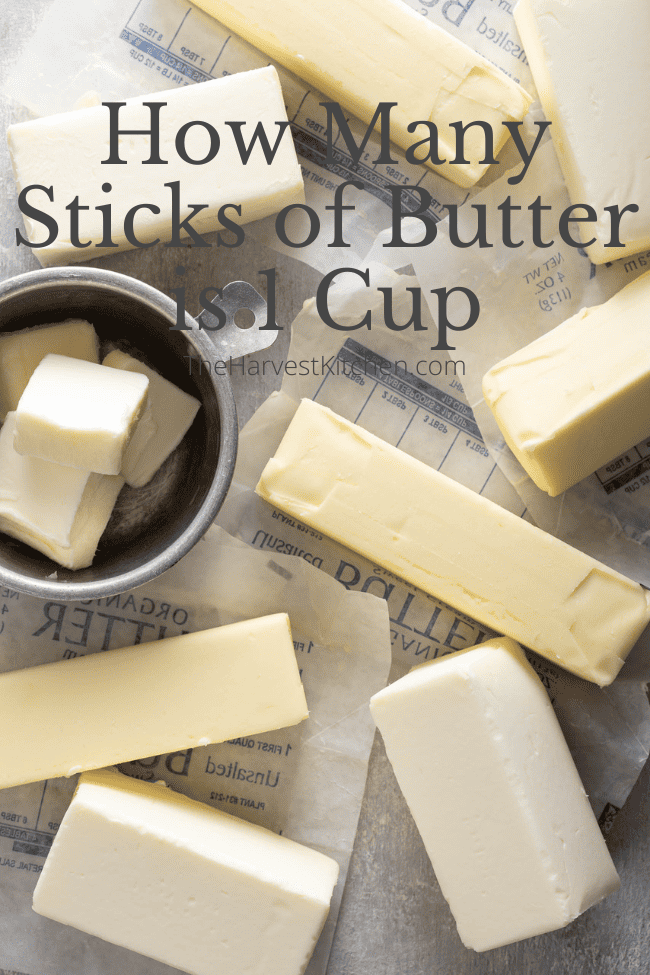

How Many Sticks of Butter Is 1/2 Cup? The Simple Math Behind Every Kitchen Measure