Madoff Explained: The World’s Biggest Ponzi Scheme That Upended Wall Street

Madoff Explained: The World’s Biggest Ponzi Scheme That Upended Wall Street

What began as a quiet, unassuming investment firm in Greenwich, Connecticut, evolved into the most far-reaching financial fraud in modern history—a Ponzi scheme so vast it shook global markets and exposed deep vulnerabilities in the financial system. Bernard L. Madoff’s scheme, revealed in 2008, defrauded thousands of investors of nearly $65 billion over decades, luring them with promises of steady, above-market returns through a carefully engineered illusion of legitimacy.

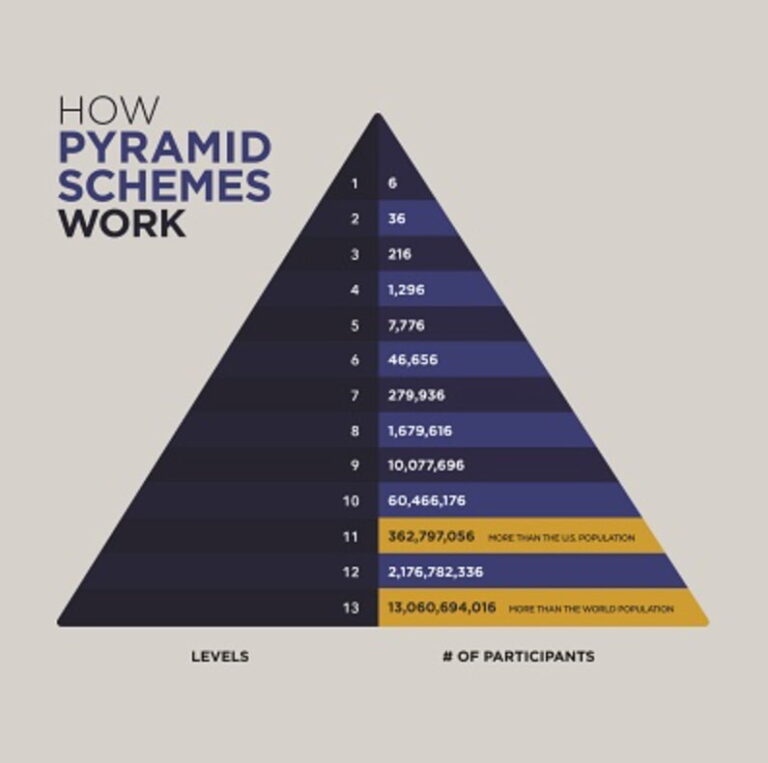

At its core, the story of Madoff’s Ponzi scheme is not just a tale of greed, but a cautionary model of how deception, regulatory failure, and complicity enabled one of the largest financial heists ever recorded. The mechanics of a Ponzi scheme rely on new investors’ money to pay returns to earlier ones—an unsustainable model that requires constant inflow to survive. Bernard Madoff exploited this flaw with clinical precision, operating a seemingly legitimate hedge fund while funneling the vast majority of incoming capital into a separate, fictitious trading account.

Investors received periodic reports citing false performance metrics—consistent monthly returns averaging 10–12%—that masked the absence of genuine investment activity. As one former employee, Harry Markopolos, later testified, “He wasn’t managing a portfolio; he was collecting new money and redistributing it.” Madoff’s operation spanned multiple layers of complexity. Behind the scenes, his firm hosted two distinct units: one purporting to engage in proprietary trading and another masquerading as a legitimate private investment vehicle.

In reality, however, the “trading” was choreographed, synthetic trades generated merely to sustain the illusion of liquidity and profit. The public face of the firm, marked by certifications like SEC registration and industry recognition, lent credibility, while independent due diligence remained astonishingly passive. As financial analyst Sarah Johnson notes, “Madoff avoided scrutiny not by hiding obvious red flags, but by ensuring no one could see what wasn’t there.” The scale of the fraud was staggering.

By 2008, when the financial crisis intensified scrutiny and demanded full revelation, Madoff’s mandated court-appointed trustee discovered not only $17 billion in actual losses but evidence of derivatives and asset transfers designed to obscure true exposure. The scheme’s longevity—decades in duration—was enabled by layers of trust: family members participated as gatekeepers, brokers were complicit through passive oversight, and auditors failed to detect by design plausible-sounding discrepancies. As Madoff himself admitted during sentencing, “I had to keep it going.

You can’t let the house of cards stand if you’re living inside it.” Roots of the fraud stretch back to the early 1990s, when Madoff began recruiting high-net-worth individuals, celebrities, and institutional investors through personal relationships rather than marketing. The firm’s reputation—bolstered by Madoff’s Membership in the New York Stock Exchange’s Berkshire Private Investment Club—served as both shield and magnet. Investors often relied on third-party nominees and audio-recorded trading “confirmations,” adding a veneer of transparency that failed to penetrate deeper scrutiny.

Insiders later revealed a culture where questioning returns was seen as suspicious, and due diligence requests were routinely swept aside. Regulatory shortcomings proved pivotal in enabling the scheme’s persistence. Although whistleblower Harry Markopolos filed detailed complaints highlighting inconsistencies as early as 2000, the SEC conducted only piecemeal reviews without launching a full investigation.

Internal SEC reports tell a troubling story: examiners noted discrepancies in trade confirmations and request logs, yet repeatedly deferred action citing insufficient evidence—even after multiple confirming investigations over years. As former SEC official Robert Khuzami pointed out, “We underestimated the sophistication of the fraud. We chased red flags, but missed the elephant in the room.” The ultimate unraveling came not from promotion or audit, but from Madoff’s own desperation.

Facing over $2 billion in wiped-out client funds and mounting pressure from family and legal counsel, he confessed during a testimony to internal investigator David Belinsky: “I couldn’t do it anymore—had to stop, admit it, protect what I could.” The failed attempt to monetize assets and secrecy over off-balance-sheet entities deepened the deception, delaying exposure but accelerating collapse when775 investors came forward. After Madoff’s sentencing to 150 years in prison and the subsequent asset recovery efforts, the scandal triggered sweeping reforms. The SEC overhauled engravings around periodic reporting, audit transparency, and whistleblower protections.

Yet the case remains a stark reminder: even the most perceived institutions of trust can harbor rot when oversight fails and human judgment falters. Madoff’s scheme did not simply defraud individuals; it exposed systemic flaws in how markets monitor, regulate, and protect investors. In retrospect, the Madoff Ponzi scheme stands not as an outlier but as a crystallizing case study—proof that financial integrity depends not on reputation, but on relentless scrutiny, accountability, and a culture unwilling to accept unreported returns.

The world’s biggest scandal was, at heart, a failure of systems. And in that failure, more than Madoff alone, lies the enduring lesson for guardians of finance.

How the Ponzi Mechanism Operated Beneath the Surface

At the heart of Madoff’s scheme was a deceptively simple financial illusion: returns were powered not by honest trading but by a continuous flow of new capital.Each monthly payout to investors was funded not by profitable enterprise, but by coin extracted from later investors, creating an expanding pyramid of obligation. This model depends on an endless influx of fresh money—a fragility that becomes fatal as redemption requests grow. Madoff’s operation mimicked normal market behavior through fabricated trading records.

For every $1, the firm supposedly returned $10, investors were shown generated profits via “legitimate” trades in coercive or synthetic fashion—often with counterparties like over-the-counter brokers whose names rarely surfaced. But forensic analysis later revealed no real execution: trades were internal imitations, recorded solely to preserve the illusion. Why did so many trust such a system?

Psychological bias played a critical role—many investors were seduced by Madoff’s longstanding reputation, personal referrals, and a carefully curated facade of respectability. As behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman explained, “Once a shady figure becomes a trusted brand, people stop seeing inconsistency. They prefer the narrative over anomaly.” This trust, reinforced by silence from regulators and auditors, allowed Madoff to operate undetected for years.

Key Red Flags Ignored by Regulators and Clients

Despite Madoff’s insistence on invincibility—“My strategy is simple, disciplined, and untested by history”—several warning signs were documented long before exposure. Yet they were dismissed, overlooked, or buried beneath layers of documentation designed to seem legitimate. - **Inconsistent Trade Confirmations**: Requested documentation often lacked individual trade tickets, instead presenting boilerplate forms signed with generic consent language.- **Lack of Independent Verification**: No third-party audit confirmed actual asset ownership behind reported returns, a cornerstone of legitimate hedge fund operations. - **Unrealistic Consistency**: Returns remained remarkably steady month-to-month, unaligned with market volatility—a red flag for synthetic generation. - **Restricted Access**: Investors were denied direct access to underlying securities and received no regular delivery receipts, violating basic due diligence practices.

- **Family Control and Secrecy**: Key decision-makers, including Madoff’s son Mark, managed operations with minimal external oversight, limiting accountability. These anomalies were noted repeatedly by whistleblowers, third-party brokers, and even academic researchers who analyzed public disclosures but failed to act. The absence of meaningful inquiry created a vacuum of accountability.

Legacy and Lessons Learned

Though Madoff’s empire collapsed under regulatory and legal strain, the scandal left indelible marks on finance. The SEC’s mishandling prompted reforms in reporting standards and whistleblower incentives, while investor education campaigns now emphasize the importance of skepticism, transparency, and independent verification. Institutional investors reassessed risk models, placing more emphasis on operational due diligence than reputation alone.Yet the deeper impact lies in cultural awareness: trust in finance requires more than credentials—it demands relentless scrutiny. Madoff exploited a system built for loaded credibility, exploiting human judgment and institutional complacency. As former Wall Street compliance officer Elizabeth Mansfield stated, “Trust is fragile; it’s not earned once—it’s challenged constantly.” The world’s largest Ponzi scheme was not just a void of wealth—it was a mirror held up to an industry, and a global market, that had grown too confident in appearances and too slow to verify truth.

In the end, Madoff’s scheme remains a defining case

Related Post

Unlock Italy’s Heart: The Ultimate Traplestrip Experience Through the Trailing Trails of Touring Guide Traplestrip

Sonya Chagas: A Trailblazing Force in Tech Leadership and Inclusive Innovation

Steve Paulson’s KTUV Bio: The Quiet Resilience Behind a Life Touched by Earthquake, Love, and Time

Examining the Digital Impression: Gulak's Content Strategy