M vs L: Which Size Is Bigger? The Science Behind the Measurement

M vs L: Which Size Is Bigger? The Science Behind the Measurement

In a world increasingly driven by data, clarity in sizing matters—especially when distinguishing between unit measurements like millimeters (M) and liters (L). One of the most persistent questions in everyday applications—from beverage storage to industrial logistics—is whether M is truly larger than L. While superficially counterintuitive—given vastly different units—this inquiry demands a precise, physics-informed comparison.

Understanding the true scale relationship between millimeters and liters isn’t just academic; it informs product design, packaging choices, and quantified space usage across industries. The fundamental difference between M and L lies in their domains: millimeters measure linear distance, typically used in physical characteristics such as screen depth, screw threads, or container wall thickness, while liters quantify three-dimensional volume, essential for liquids and bulk goods. This foundational distinction shapes how size comparisons are interpreted.

To assess “which is bigger” requires anchoring both terms to a shared metric—volume or linear space—then cross-referencing accordingly.

The Unit Divide: Millimeters vs Liters Explained

Millimeters (mm) are part of the metric length system, representing one-thousandth of a meter. Their utility spans precise engineering and consumer product specs.For instance, a smartphone screen depth might measure 8 mm, a typical nail’s thickness could be 3 mm, and steel reinforcement bars often fall in the 10–25 mm range—all linear measurements grounded in spatial height or diameter. Liters (L), conversely, measure volumetric capacity, equal to one cubic decimeter. A standard water bottle holds 0.5 L (500 mL), a gallon equals 3.785 L, and fuel tanks are quantified in liters to reflect container volume.

This volumetric focus means L inherently encompasses far greater spatial extent than mm, regardless of context. “Apparent contradiction arises because M and L describe different dimensions—and equating them directly is fundamentally flawed,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a metrology specialist at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures.

“A meter is a thousand millimeters, but a meter does not equal a liter. Volume and linearity are distinct physical concepts.”

To resolve the M vs L comparison, standardized conversion reveals the truth: 1 liter equals exactly 1,000 cubic millimeters (1 L = 1,000 mm³). This conversion clarifies that within a cubic space of 1 meter on each side (1 m³), there are 1 million liters—enormous volume energy tied to just one cubic meter.

Yet, in standalone comparisons—depth vs. volume—M remains shorter than any meaningful L value.

Physical Dimensions: Volume and Linear Measurements in Context

Consider a sealed water bottle, a common object for size evaluation: - Its wall thickness might measure 2 mm (linear), yet its internal capacity is ~0.75 L (liters). - A soda can edge height could be 12.5 cm (125 mm)—over 100 times taller than 12.5 mm in linear terms—but its volume is approximately 0.33 L, illustrating how height unlike linear scale.- A smartphone charger’s USB-C port spans roughly 5.5 mm deep—slightly less than a standard 0.1 cm—but its cable’s cross-section (if thick at 4.8 mm) matters more in M terms than L volume. Volume-based comparisons reveal clear superiority of L: a liter single-handedly fills 1,000 mm in depth when layers of 1 mm stack vertically, whereas even the tallest M dimensions rarely approach 1,000 mm at the scale of volume.

Industrial standards reinforce this clarity: packaging specifications prioritize volume (L) for shipping, storage, and cost—between beverages, chemicals, or electronics—because volume determines usable space and material quantity.

Linear metrics like M inform component fit but never surpass volumetric scale in overall magnitude.

Visualizing Scale: Analogies and Real-World Implications

Imagine comparing a cubic block of 1,000 mm (1 meter) on each side versus a box holding 1 liter of liquid: - The cubic block encloses space equivalent to 1 million mm³, but only holds 1 L—less than half a liter in volume-by-volume terms. - A basketball holds roughly 1.5 liters, its max diameter around 24 cm—more than ten times the depth of a standard areogram measured in millimeters. These analogies demonstrate: - **Height alone (mm) doesn’t equate to capacity (L).** - **Volume governs usable space more than dimensional height.** - **Liters dominate in applications requiring precise volume control—drinks, fuel, chemicals.** - **Millimeters guide precision but never encompass the scale liters represent.** Automotive engineers reflect this: “Battery packs are sized by volume, not board thickness.A 300 L EV battery holds vastly more stored energy than 300 mm of electrode thickness,” notes Marco Chen, battery systems lead at VoltCore Industries. “You can’t optimize energy density without volume metrics.”

Lighter use of M risks overestimating real-world necessity; overreliance on L alone misses critical engineering fit. The key lies in context: mm excels in dimensions requiring precision—fitting parts, ergonomic design—while liters dominate fluid and bulk handling requiring precise volume quantification.

Industry Applications Highlighting the M-L Divide

- **Beverage Industry:** 2-liter bottles define consumer size; 2 mm caps fit snugly, but volume guarantees freshness and cost-per serving.- **Construction:** Reinforcing steel’s 16 mm diameter supports structures without implying a 16 L column—volume matters for load capacity, not diameter alone. - **Electronics:** Screen depth (8–12 mm) ensures touch responsiveness, while 0.06 L internal battery volume dictates usage time. - **Logistics:** Pallet pallets stack by height (often 1.2–1.5 m, or 1,200–1,500 mm), yet load weight in kilograms—not linear height—guides safety.

Ultimately, the debate of M vs L hinges on perspective: linear vs volumetric, height of a screw vs volume in a tank. While M offers nuanced dimensional insight, L reveals the true spatial scale affecting functional design and resource efficiency. There is no ambiguity—liter is significantly “bigger” in volume than millimeter, irrespective of unit type.

In practice, M defines space in dimensions; L quantifies the capacity within that space.Choosing between them demands clarity on the task: precision assembly wins with millimeters; operational scaling depends on liters. When measuring performance, shelf life, or structural load, liters provide the definitive answer—since volume is volume, regardless of measurement system. Under the surface, every inch, centimeter, millimeter, or liter encodes critical physical reality.

The M vs L question isn’t about superiority—it’s about correct measurement for correct decisions. What matters is knowing which unit tells the full story.

Related Post

Need You Tonight: A Deep Dive Into The Emotional Core of Inxss’ Anthem That Sets the Soul on Fire

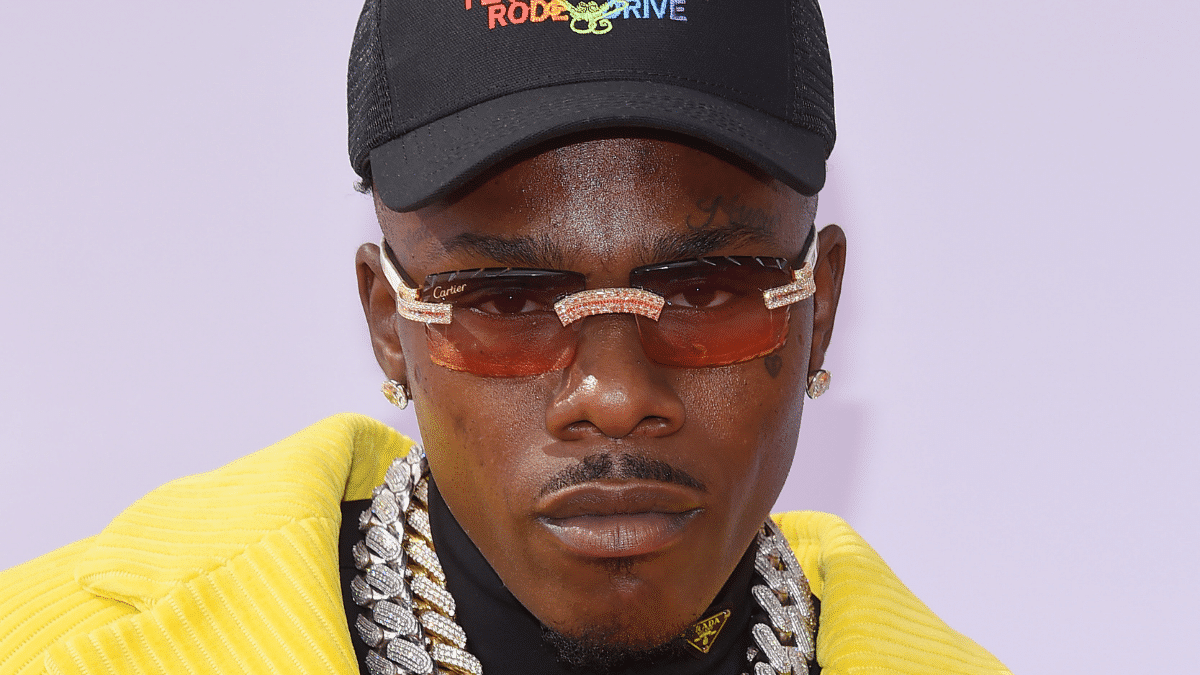

Dababy Net Worth The Untold Success Story of a Rising Hiphop Star: 2024 Deep Dive Into Rpper’s Welth

Understanding The Gender Identity Of Britney Griner: A Deep Dive into a Cultural and Personal Journey