Labeling The Urinary System: The Body’s Silent Filtration Network

Labeling The Urinary System: The Body’s Silent Filtration Network

The urinary system, a complex and elegantly organized network within the human body, performs a vital yet often overlooked role in maintaining internal balance. Far more than a passive drainage pathway, this system actively manages fluid levels, filters metabolic waste, and regulates essential chemical constituents of blood. From the moment urine begins to form in the kidneys to its final excretion via the urethra, every component—from nephrons to bladder—works in precise coordination to sustain homeostasis.

Understanding the anatomy, function, and clinical significance of each part reveals a dynamic system essential for health and survival.

At its core, the urinary system includes six major components: the kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra, and radially linked networks of ducts that begin with the renal pelvis and extend through pulmonary and systemic pathways. The kidneys, four bean-shaped organs nestled in the retroperitoneal space, are the system’s command centers.

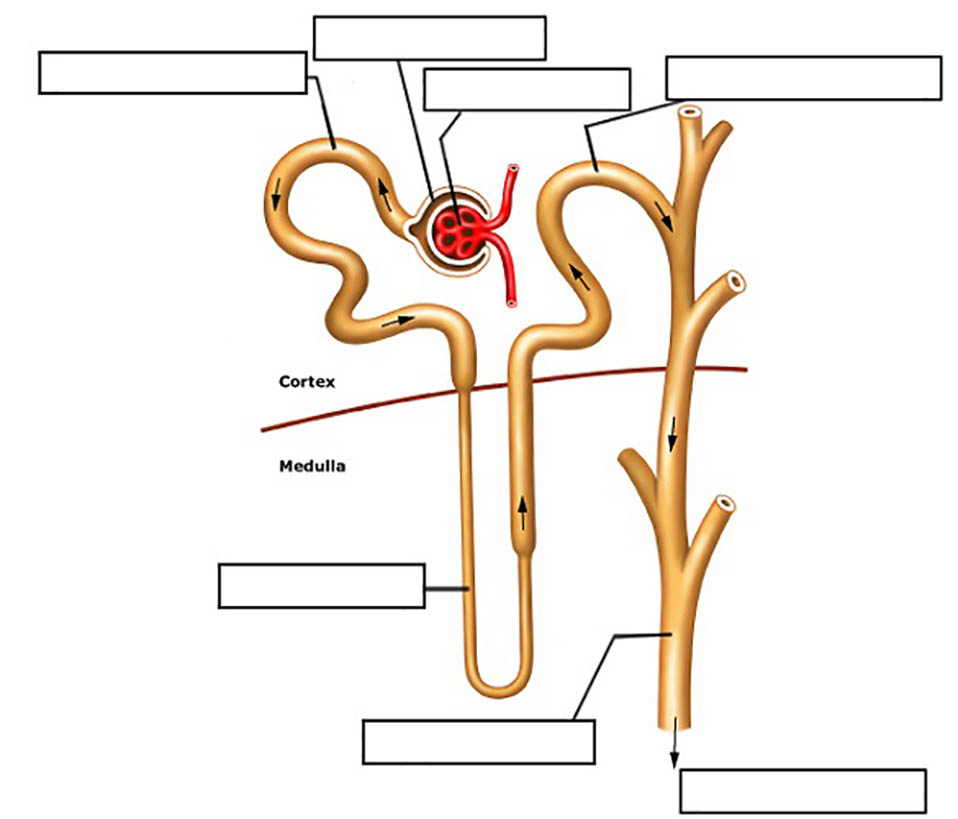

Each kidney contains over a million nephrons, microscopic filtration units responsible for separating toxins and surplus substances from blood. "This intricate filtration process begins where blood enters the kidneys via the renal arteries, delivering ~20% of the heart’s output per minute—enough to filter all blood every 24–30 hours," notes nephrologist Dr. Elena Martinez in a recent review.

The Kidneys: Primary Filtration Powerhouses

The kidneys operate through a two-stage filtration mechanism: glomerular filtration followed by tubular reabsorption and secretion. Blood flows into the glomerulus—a network of capillaries encased in Bowman’s capsule—where pressure forces water, glucose, amino acids, and waste products through a selective barrier. The resulting filtrate enters renal tubules, where vital substances like sodium and potassium are reclaimed, and harmful compounds—such as urea, creatinine, and ammonia—are excreted.

This dynamic balance prevents accumulation of toxic byproducts while conserving essential nutrients.

This adaptive response is crucial during exercise, fasting, or illness.

Flowing from the renal pelvis like narrow, muscular pipelines, the ureters transport filtered waste from kidneys to the bladder.

Each ureter is approximately 25–30 cm long, descends through the pelvic fascia, and empties via the ureterovesical junction. Their movement—by peristaltic contractions—ensures one-way urine flow, preventing backflow and infection. Because ureters lack smooth muscle layers beyond the proximal segment, their function depends heavily on this rhythmic muscle activity.

Positioned retroperitoneally and angled downward, they avoid compression by abdominal structures, optimizing drainage. However, their lack of valves renders them vulnerable to vesicoureteral reflux, a condition where urine flows backward, increasing infection risk—particularly in children, where it contributes to recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).

The internal and external ureteric muscles—only active in the proximal renal and distal bladder regions—generate peristaltic waves through coordinated contractions.

The Bladder: A Dynamic Storage Reservoir

The bladder, a muscular hollow organ in the pelvis, serves as a temporary reservoir for urine. Composed of four layers—mucosa, muscularis propria, adventitia, and a fibrous capsule—its capacity ranges from 400 mL at rest to over 700 mL when stretched. The detrusor muscle, a thick smooth muscle layer, contracts during urination to expel urine, while the internal and external urethral sphincters regulate release.

The urine storage process involves gradual filling; sensations of urgency emerge only when bladder volume exceeds ~200–250 mL, as stretch receptors in the detrusor trigger neural signals to the spinal cord. Despite this lag, frequent monitoring of urinary habits remains vital—overactive bladder syndrome, affecting millions, disrupts normal function due to involuntary detrusor contractions, often linked to neurologic changes, aging, or irritants like caffeine.

The external sphincter, made of skeletal muscle, provides voluntary control—enabling conscious hesitation or evacuation.

The Urethra: Final Conduit to Extroneous Exit

The urethra, a 15–20 cm tube extending

Related Post

Ryan Callaghan Bio Wiki Age Wife Podcast Meat Eater and Net Worth

The Shocking Origins of Cool Gang Signs: Decoding the Symbols That Define an Urban Legacy

Colloportus: The Enigmatic Bridge Between Earth and Subterranean Realms

The Visionary Legacy of Mejiro McQueen: Architect of Pixar’s Artistic Soul