Is There a Most Racist Country in the World? Unpacking Systematic Exclusion and Deep-Rooted Prejudice

Is There a Most Racist Country in the World? Unpacking Systematic Exclusion and Deep-Rooted Prejudice

The question “Is there a most racist country in the world?” lingers in global discourse, sparking fierce debate over whose societies perpetuate the deepest inequities. While racism manifests differently across borders—shaped by colonial legacies, institutional structures, and cultural norms—certain nations stand out for their entrenched systems of racial exclusion and systemic discrimination. Gender, ethnicity, skin color, and immigration status often determine access to power, education, and justice, revealing patterns of marginalization that go far beyond isolated incidents.

The debate challenges the myth of neutrality, urging scrutiny of both overt hatred and subtle, institutionalized biases.

Defining racism in a measurable, global context remains inherently complex. Most researchers rely on indices tracking legal frameworks, social attitudes, and economic disparities rather than attempting a singular ranking.

Yet recurring patterns emerge: countries with histories of colonialism, prolonged segregation, or ethno-nationalist policies frequently exhibit acute racial fault lines. These systems are sustained not only by prejudice but by laws, bureaucratic practices, and cultural narratives that legitimize inequality. Whether measured through hate crime rates, apartheid-like structures, or systemic access barriers, certain nations stand out in comparative studies for their persistent racial disparities.

The Structural Foundations of Inequality

Understanding modern racism requires examining how historical injustices evolve into present-day structures. Many so-called “racist countries” maintain legal or de facto hierarchies rooted in colonial or apartheid-era practices. For example, South Africa still grapples with socioeconomic divides dating back to apartheid, where racial classification determined housing, education, and employment opportunities.Though apartheid formally ended in 1994, its legacy persists: according to the World Bank, Black South African households earn, on average, just 46% of what white households earn—a stark reflection of enduring inequality. Similarly, Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya Muslim minority illustrates how state-sponsored exclusion can reach genocidal proportions. The 1982 Citizenship Law rendered Rohingya “foreigners” in their own land, stripping them of basic rights including freedom of movement and census recognition.

Since 2016, widespread violence and forced expulsions have displaced over one million Rohingya, highlighting how state-perpetrated racism manifests through institutionalized dehumanization. The persistence of such systems reveals racism is often embedded in governance, law enforcement, and public policy. In Brazil, for instance, Afro-Brazilians face disproportionate rates of police violence, homicide, and poverty—factors compounded by cultural stereotypes linking race to criminality.

While Brazil rejects official racial categorization, data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics show Black Latin Americans are eight times more likely to be killed by police than white Brazilians—a statistic specifying structural bias.

Racial discrimination also thrives in social norms and cultural practices, where prejudice shapes daily interactions and opportunity. In Thailand, the state’s official classification of ethnic minorities—such as the Karen and Hill Tribes—as “foreigners” despite generations of residence restricts legal rights and fuels marginalization.

Though less overt than apartheid, such classification reinforces invisibility and economic exclusion. Similarly, in parts of the Middle East, migrant domestic workers from South Asia and Africa face systemic abuse under *kafala* sponsorship systems, where employment is tightly controlled by employers, leaving little recourse for rights violations. These examples underscore that racism operates at multiple levels—legal, institutional, and social—with each layer reinforcing the others.

The absence of universal laws criminalizing racism does not equate to absence of prejudice; rather, it signals normalization. Societies with high levels of racial stratification often lack public reckoning or meaningful accountability mechanisms, enabling biases to persist unchallenged over decades.

Global Indices and Research: How Racism Is Measured

While no definitive “most racist” country exists on a single scale, international indices assess racism through measurable indicators: hate crimes, discrimination reports, social trust, and inclusion.Groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights publish annual data that illuminate patterns of racial bias across nations. The Global Galway Project, a cross-national study measuring attitudes toward diversity, reveals that countries with higher racial resentment scores—such as the United States and some European nations—tend to exhibit greater societal polarization. In the U.S., surveys consistently show systemic anti-Black sentiment, rooted in slavery’s enduring legacy, with police violence and housing segregation serving as visible markers.

Despite progressive legal frameworks, racial inequity in education, incarceration, and wealth accumulation reveals persistent disparities. In Europe, rising populist movements have amplified xenophobic rhetoric, particularly toward Muslim and Black immigrants. Nations like Hungary and Poland rank high on anti-immigrant sentiment in Eurobarometer polls, correlating with restrictive policies and state-backed narratives that frame non-white populations as threats.

Conversely, countries like Sweden and the Netherlands, though often praised for inclusivity, struggle with institutional racism—Evidence uncovering bias in hiring, education, and healthcare. The UN Human Development Report emphasizes that racism is not merely an individual failing but a societal structure requiring systemic intervention. “Racism flourishes where power imbalances go unchallenged,” states the report, highlighting the role of education reform, inclusive policymaking, and truth-telling about historical wrongs as essential tools for transformation.

Case studies also reveal nuance in measured racism. South Africa’s post-apartheid progress—through truth commissions and affirmative action—reduced overt state racism but failed to fully dismantle economic and spatial segregation. Similarly, Japan’s quiet discrimination against the *Burakumin* and foreign residents persists despite its image as a homogeneous society.

These examples illustrate how deep-seated bias resists quick fixes, demanding sustained political will and inclusive civic participation.

The Path Forward: Addressing Racism Through Equity and Education

Confronting racism requires moving beyond symbolic gestures to structural reform. Nations that make measurable progress—such as Canada with its multicultural policies and targeted anti-racism initiatives—show that inclusive governance fosters greater equity.Yet systemic change hinges on combining legal protections with cultural shifts, including inclusive education, media representation, and community engagement. Experts agree that acknowledging historical injustices is foundational. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, despite limitations, opened space for public reckoning.

Similarly, Germany’s rigorous Holocaust education embeds anti-racist values in youth. In the U.S., ongoing debates over reparations and policing reform reflect societal efforts to address deep-rooted harm. Ultimately, the absence of a universally “most racist” country underscores a broader truth: racism is not confined to isolated nations but circulates globally in varied, evolving forms.

What defines a racist society is not the absence of diversity but the persistence of exclusionary systems. Addressing racism demands persistent accountability—through policy, education, and collective memory—to build inclusive futures where dignity is not dictated by race, ethnicity, or background. In navigating this complex terrain, clarity emerges not from seeking a single worst offender, but from recognizing shared responsibilities: to document inequities, challenge prejudices, and empower marginalized voices.

Only through such sustained, honest effort can the global community begin to redefine fairness and justice for all.

Related Post

응, 그의 이름이 알렉스 포우어 — The Ultimate Guide To The Actor Behind Legolas

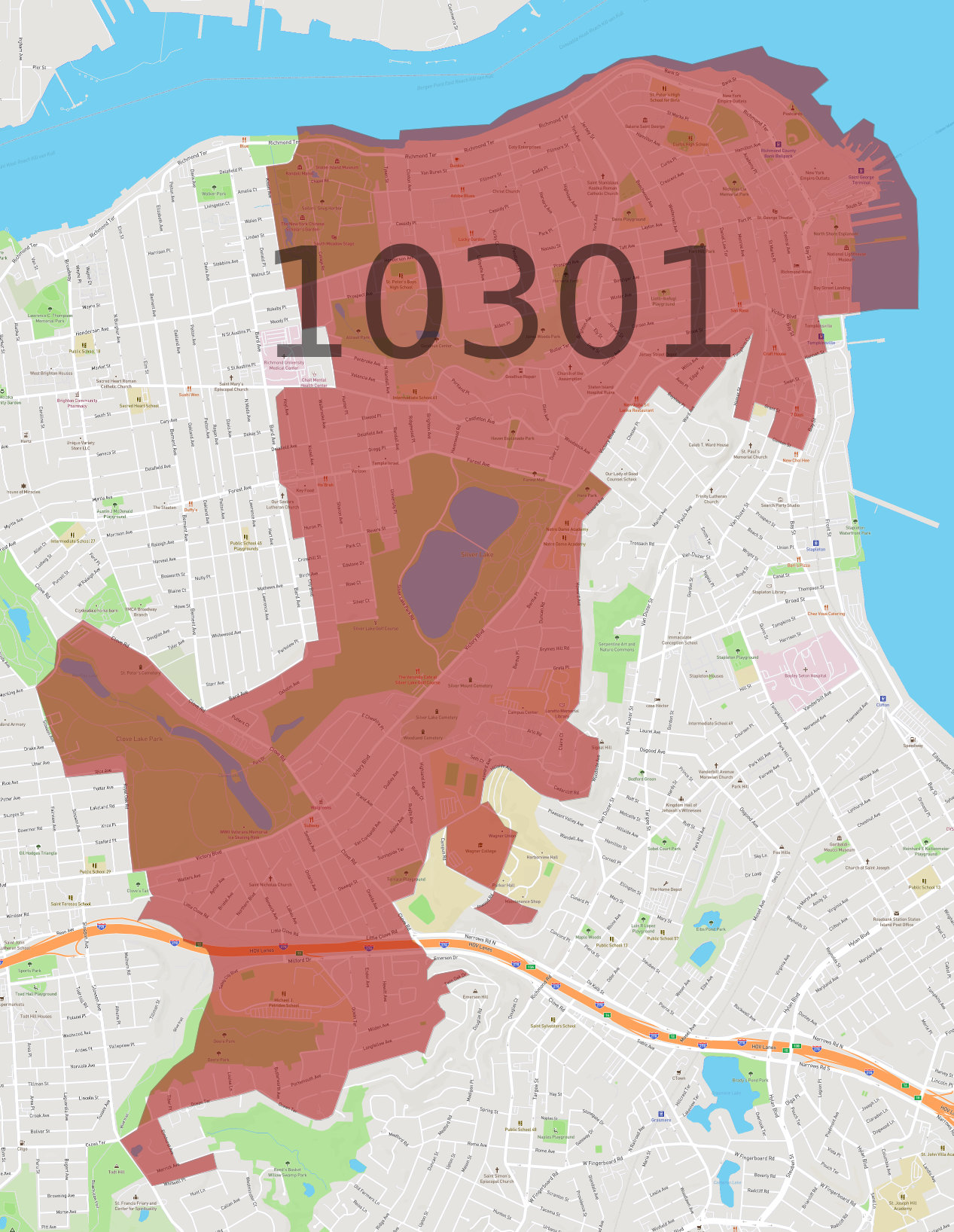

Staten Island Zip Code 10301: Where Urban Life Meets Island Tradition

Meet Maureen Blumhardt Charles Barkleys Wife of Over 30 Years

What Happened to Dexters’s Mom: The Tragic Tale Behind the Beloved Character Actress