Is Sublimation Endothermic or Exothermic? The Thermal Truth Behind Phase Change Mystery

Is Sublimation Endothermic or Exothermic? The Thermal Truth Behind Phase Change Mystery

When a solid transitions directly into vapor without passing through a liquid state—a process known as sublimation—its energy behavior defies simple categorization. At first glance, the question of whether sublimation absorbs or releases heat may seem abstract, but its implications stretch from atmospheric science to industrial drying and even the preservation of historical artifacts. Far from ambiguous, the answer lies firmly in thermodynamics: sublimation is unequivocally an endothermic process, demanding heat input to overcome intermolecular forces and enable molecules to escape into the gas phase.

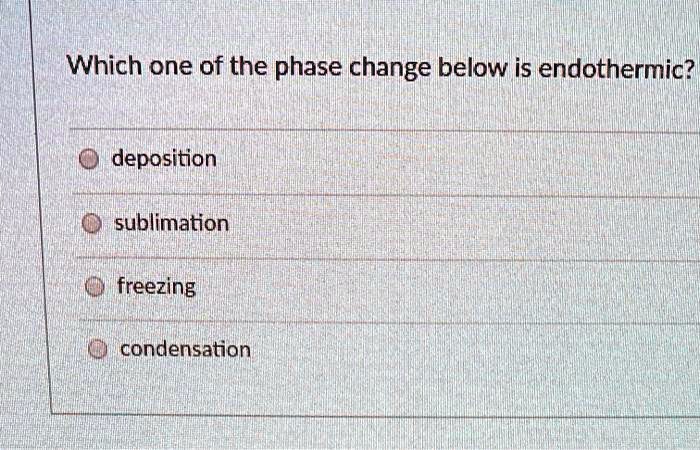

Sublimation occurs when molecular stability is overcome by sufficient energy, breaking bonds that hold solids in rigid structure. This transformation does not involve melting, so no phase change intermediate like liquid formation occurs to absorb or release heat. Instead, energy is supplied entirely to escape forces, making the process endothermic by definition.

According to foundational principles of thermodynamics, “an endothermic process is one that requires external energy to proceed, resulting in a net uptake of heat from the surroundings,” a process perfectly exemplified by sublimation. Quantitatively, the energy required for sublimation is quantified by the enthalpy of sublimation (ΔHsub), which combines both the enthalpy of fusion (to melt the solid) and the enthalpy of vaporization (to form gas). For iodine, a classic sublimation model, ΔHsub amounts to approximately 51 kJ/mol—a value derived from precise calorimetric studies confirming energy absorption during solid-to-vapor transition.

This contrasts sharply with exothermic processes like condensation or crystallization, where energy is released when molecules release binding forces and transition to lower-energy states. Understanding the Physics: Bond Breaking and Energy Uptake The endothermic nature of sublimation stems from the necessity of breaking intermolecular bonds without first entering a liquid phase. In most phase transitions, energy input first raises temperature or drives melting, followed by latent heat absorption during phase change.

But sublimation skips the liquid step: molecules must directly overcome cohesive forces holding them in the solid lattice. This requires disruptive input energy, manifesting as a measurable heat uptake from the environment. Consider dry ice—solid carbon dioxide—when exposed to air.

As it sublimes at -78.5°C, it draws heat from its surroundings, cooling the air. This cooling effect is a direct signature of endothermic behavior: the solid sinks in temperature because it is consuming thermal energy. Contrast this with water freezing at 0°C, where energy is released, causing the immediate environment to warm.

Such temperature anomalies provide empirical proof that sublimation saps heat, not releases it. Real-World Applications Driven by Sublimation’s Endothermic Profile The practical significance of sublimation’s endothermic characteristics extends across multiple domains. In freeze-drying (lyophilization), a process critical for preserving pharmaceuticals, food, and biological specimens, sublimation removes moisture from materials at low temperatures.

By controlling sublimation conditions, scientists maintain structural integrity and activity—essential for vaccines and lab samples alike. The energy absorbed during this phase change ensures water vapor escapes without damaging delicate molecular frameworks. In atmospheric science, sublimation plays a vital role in polar and high-altitude regions.

Seasonal snow and ice in deserts or mountainous zones can sublimate directly to vapor under dry, cold conditions, influencing humidity, precipitation patterns, and even cloud formation. Aridity accelerates sublimation, contributing to desertification cycles and shaping local climate dynamics. Environments like the Atacama Desert experience significant moisture loss via sublimation, exemplifying how energy dynamics regulate natural systems.

Industrial applications further exploit sublimation’s thermal demands. In the manufacture of high-purity materials—such as certain semiconductors or stage chemicals—sublimation is used to generate clean vapor phases free of impurities that might be left behind in liquids. The endothermic energy input acts as a purification mechanism, capitalizing on selective phase behavior to enhance product quality.

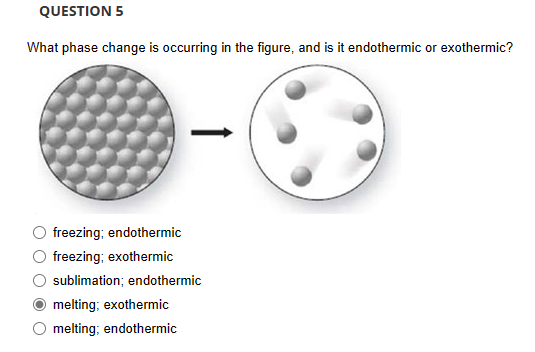

Comparing Sublimation to Latent Processes: A Thermodynamic Taxonomy To fully grasp why sublimation is endothermic, it helps contrast it with other phase transitions enriched in latent heat. Condensation, the reverse of vaporization, releases heat as gas molecules release energy to bond into liquid. Similarly, melting and freezing involve latent heat of fusion—energy exchanged at constant temperature during solid-liquid transition.

In each case, thermal energy moves between phases in a thermodynamically balanced exchange: absorption in vaporization, release in condensation. Sublimation, however, occupies a distinct category: it demands input to shift from ordered solid to disordered vapor, with no return through liquid intermediates. This fundamental difference places it squarely in the endothermic class.

Thermodynamic tables consistently classify sublimation under endothermic processes due to the positive enthalpy change and clear energy requirement from system surroundings. Molecular Insight: Why Energy is Absorbed At the molecular level, the endothermic character of sublimation reflects the energy needed to exceed binding potentials. In solids, molecules vibrate within fixed positions, bound primarily by van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, or ionic lattices.

Liquefaction requires overcoming these forces gradually through thermal input; sublimation intensifies this by demanding leg-level energy to escape entirely. Studies using calorimetry and spectroscopy confirm that sublimation values align with theoretical predictions of bond-breaking energy. “Sublimation is not just a phase change—it’s a molecular endeavor,” notes Dr.

Elena Torres, a physical chemist specializing in phase transitions. “Molecules must confront lattice stability head-on, absorbing precise energy amounts to escape into vapor, making it a textbook example of an endothermic process.” The Broader Scientific Impact Beyond practical uses, understanding sublimation informs broader scientific inquiry. In planetary exploration, sublimation shapes surface chemistry on comets and moons with icy regolith.

The comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, studied by the Rosetta mission, exhibits intense sublimation of water ice under low-pressure conditions, releasing gases and dust that form its iconic coma and tails. Temperature measurements during such events confirm energy absorption, reinforcing the endothermic framework. In materials research, the energy profile of sublimation guides decisions in vapor transport processing and thin-film deposition.

By controlling sublimation rates through heat and pressure, scientists direct atomic-scale growth, enabling innovations in electronics, optics, and nanotechnology. Ultimately, sublimation’s endothermic nature is not merely a thermodynamic footnote but a cornerstone concept linking molecular behavior to global systems. From freeze-dried medicines to comet tails, the process demonstrates how precise energy exchange governs both natural phenomena and engineered solutions.

This category of phase change—absorbing heat to liberate molecules—reflects nature’s elegant mechanism for energy transfer, shaping processes as diverse as climate dynamics and semiconductor manufacturing. Sublimation, therefore, stands definitively as endothermic: a phase shift demanding energy to unlock vapor, a controlled energy infusion that powers countless applications and natural wonders alike.

Related Post

Paula Andrea Bongino Dan Bongino Wife Age Health and Net Worth

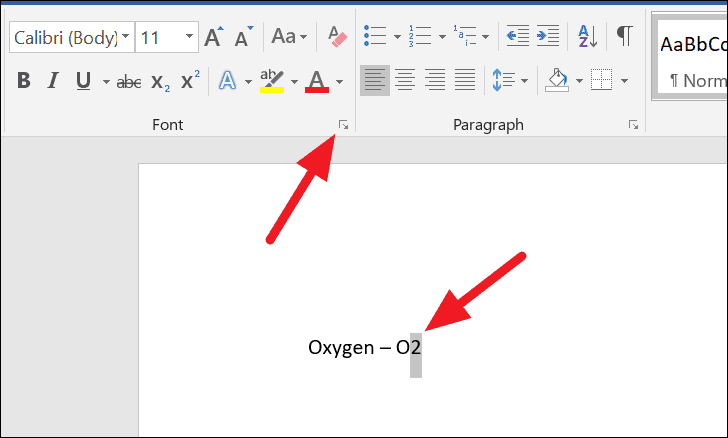

How Do You Add Subscript in Word? Master Precision Typing Without the Stress

Raymond Washington: The Controversial Figure Who Redefined Mass Movements and Sparked Enduring Debate