Is Carbon a Nonmetal or Metal? Unlocking the Element That Shapes Our World

Is Carbon a Nonmetal or Metal? Unlocking the Element That Shapes Our World

Carbon occupies a unique and pivotal position in the periodic table—straddling the boundary between nonmetals and metalloids, yet serving essential roles in both categories. Though often classified as a nonmetal due to its electronegativity, complex bonding behavior, and physical traits, carbon’s versatility defies rigid categorization. Its ability to form an astonishing diversity of allotropes—including diamond, graphite, and graphene—while simultaneously exhibiting properties linked to metals, makes it a cornerstone of modern science and industry.

Understanding whether carbon is a nonmetal or metal is not just an academic exercise; it reveals profound insights into its chemical behavior, structural forms, and indispensable contributions to technology, biology, and materials science.

Carbon sits at the heart of the nonmetal group in the periodic table, displayed prominently in Group 14 alongside silicon, germanium, tin, and lead. Trioed with oxygen and nitrogen—distinctive nonmetals that define elemental chemistry—carbon shares key characteristics: poor electrical conductivity, high thermal stability in certain forms, and the ability to form intricate molecular frameworks.

Unlike metals that readily lose electrons to create cations, carbon relies heavily on covalent bonding, sharing electrons to build stable, three-dimensional networks. This electron-sharing nature underpins its nonmetallic electronegativity (2.55 on the Pauling scale), a value higher than many sequential elements but insufficient alone to define metallic behavior. As chemist Dr.

Elena Marquez of the Materials Science Institute notes, “Carbon’s role isn’t about identity—it’s about adaptability. Its bonding patterns determine whether it acts as a derivative of carbon or embodies metallic traits.”

Yet, carbon defies strict classification. Its ability to exist in multiple structural allotropes with dramatically different properties highlights its duality.

Graphite, a layered form, conducts electricity due to delocalized electrons between carbon layers—behavior reminiscent of metals but arising from shared electron clouds rather than ionic transfer. Diamond, in contrast, boasts a rigid tetrahedral lattice where each carbon atom shares four covalent bonds, rendering it insulating and exceptionally hard—classic nonmetal hallmarks. These contrasting forms illustrate carbon’s propensity to resemble either nonmetal or metal depending on its molecular architecture.

NanOGraphene further extends this boundary; as a two-dimensional sheet, it exhibits electron mobility approaching that of metals, yet retains its carbon-based molecular identity, enabling breakthroughs in electronics and nanotechnology.

Historically, carbon’s nonmetallic nature shaped early chemical understanding. Found in organic compounds from methane to carbohydrates, its bonds underpin life’s molecular machinery—proteins, DNA, and carbohydrates all rely on carbon’s tetravalency and covalent flexibility. Yet its role extends well beyond biology.

Industrially, carbon forms the backbone of fuels, plastics, and advanced materials. Diamond, the hardest natural material, is prized in cutting tools and high-performance optics. Graphite’s lubricity and conductivity make it vital in batteries and electrodes.

Carbon nanotubes and graphene promise revolutionary advances in flexible electronics and structural composites—materials where carbon’s unique strength-to-weight ratio redefines engineering limits. As materials scientist James Whitaker explains, “Carbon doesn’t choose being metal or nonmetal—it adapts, and this adaptability is why modern technology depends on it.”

Despite its nonmetallic digital footprint, carbon occasionally exhibits metallic-like properties—but only under extreme conditions. Pressurized diamond, for instance, can become electrically conductive, shedding its purely insulating nature.

Similarly, certain carbon allotropes synthesized under high pressure or in nanoscale configurations display enhanced electron delocalization, approaching metal-like conductivity. However, such behavior stems not from fundamental metallurgy but from structural transitions. Pure carbon does not oxidize or corrode like classical metals, lacking a reactive metallic lattice.

While carbon composites reinforce metals in alloys—merging carbon’s strength with metallic ductility—the standalone element remains unclassified due to unmet metallic criteria. “Carbon may perform metallurgical roles,” says Dr. Li Wei of the Carbon Research Consortium, “but it doesn’t play the metallic game on its own.”

In summary, carbon occupies a gray area: chemically and electronically nonmetallic, yet structurally versatile enough to mirror metal characteristics under specific conditions.

Its classification transcends binary labels, reflecting a nuanced reality where bonding, allotropy, and application shape perception. From life-sustaining biomolecules to next-generation nanomaterials, carbon’s hybrid nature underpins scientific progress and industrial innovation. As research advances, understanding carbon’s dual identity—as both nonmetal and proto-metalloid—continues to deepen our grasp of elemental behavior and unlock transformative technologies.

In a world defined by material limits, carbon remains an extraordinary exception—proving that in science, boundaries often inspire breakthroughs.

Related Post

The Hidden Health Implications of 179 Cm Height: Beyond the Average Stature

Salif Lasource salif_crookboyz Bio Age Wiki Net worth Height Girlfriend

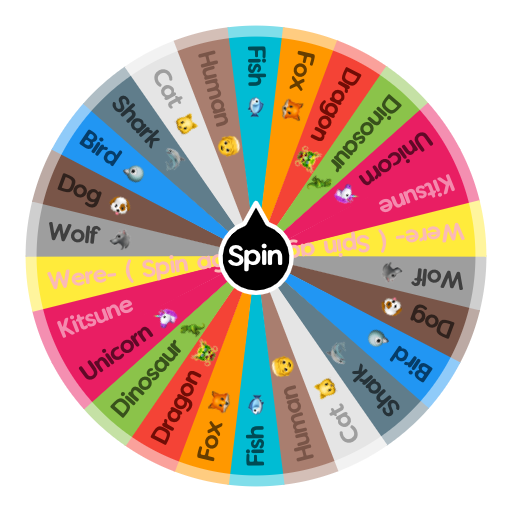

Animal Spin The Wheel Includes A Ton Of S Random Picker

Why the Kemuri Haku Comics Will Blow Your Mind: 10 Spoiler-Worthy Reasons