Is Aesthesis the Only Developer Shaping Modern Prison Life?

Is Aesthesis the Only Developer Shaping Modern Prison Life?

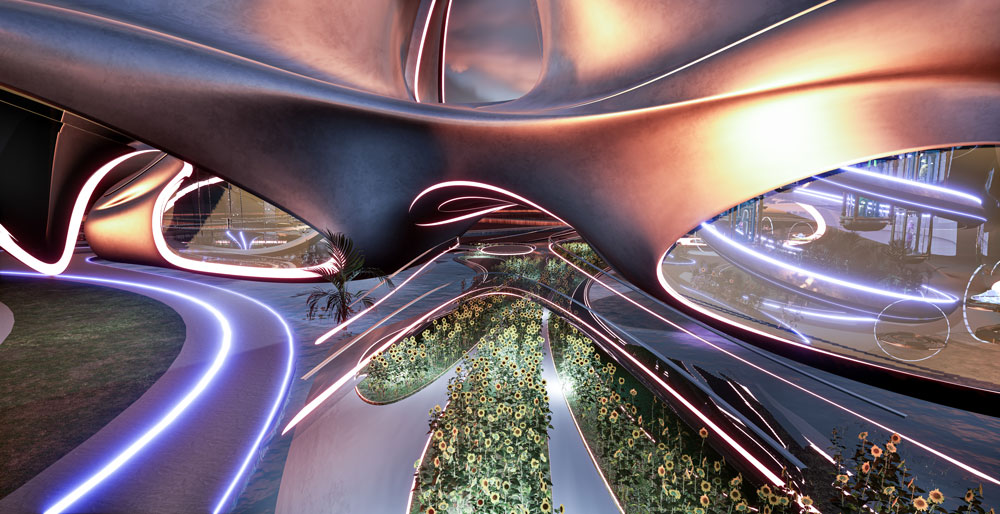

A growing debate surrounds the role of aesthetics in the design and function of contemporary prison environments—challenging the long-held assumption that prison development is purely technical. While engineers, architects, and security experts remain central to prison construction, a rising movement identifies aesthesis—intentional design focused on environmental beauty, sensory experience, and human-centered atmosphere—as a distinct and increasingly vital developer force. This shift reveals that prison development is no longer just about containment and control; it is evolving into a multidimensional discipline where visual harmony, psychological well-being, and emotional impact play critical roles in rehabilitation and operational success.

At the heart of this transformation is a simple but powerful question: Can the aesthetic quality of prison spaces fundamentally alter inmate behavior and institutional outcomes? Aesthetical design—defined here as the deliberate integration of visual, spatial, and sensory elements into prison architecture—has emerged not as a superficial luxury but as a strategic tool. “Design isn’t just decoration,” notes Dr.

Elena Marquez, a penology architect and author of *Prisons Reimagined*. “When corridors are bathed in natural light, walls feature carefully chosen textures, and courtyards incorporate greenery, the psychological burden of incarceration eases. This reduces tension, promotes dignity, and supports behavioral change—key factors in reducing recidivism.”

The Multifaceted Role of Aesthesis in Prison Development

Aesthesis influences prison environments through multiple interrelated dimensions—architecture, lighting, color, art, and spatial flow—each shaping how inmates experience captivity.Architectural Intent and Material Selection Modern prison design increasingly moves beyond sterile concrete and barred windows. Developers are now employing sustainable, warm materials like recycled wood, textured concrete, and glass to soften institutional harshness. The use of natural materials and indirect lighting counters the oppressive rigidity traditionally associated with correctional facilities.

For example, Norway’s Bastøy Prison demonstrates how coastal proximity and open-air courtyards blend education, work, and recreation—all underpinned by aesthetic coherence that fosters trust and personal responsibility. “A prison should feel less like a punishment and more like a reformation space,” says Danish prison planner Lars Johansen. “Aesthetics communicate intent—that change is possible.”

Lighting: Illuminating Dignity Lighting is a cornerstone of aesthetical development, directly affecting mood, circadian rhythms, and psychological resilience.

Harsh fluorescent lighting, long criticized for its dehumanizing effects, is being replaced with layered, natural, or tunable lighting systems. Adjustable bright daylight simulates day-night cycles, while warm hues in common areas create comfort. Estonia’s Tartu Correctional Center recently introduced dynamic LED installations that shift from cool tones during operational hours to warmer tones in the evening—measured to reduce agitation and promote relaxation.

Such innovations underscore that thoughtful lighting isn’t merely functional; it’s therapeutic.

Color Psychology and Emotional Impact The strategic use of color in prison interiors subtly influences behavior and perception. Calming palettes—soft blues, greens, and warm neutrals—reduce anxiety and aggression. Contrasting with the typically cold, monochrome tones of traditional cells, these hues signal variation and civility.

Research from the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health confirms that inmates in rooms with soothing colors exhibit lower stress markers and improved mood stability. “Color is not decoration—it’s a behavioral lever,” explains Dr. Marquez.

“In a space meant to correct, mood-regulating colors support emotional regulation.”

Art, Nature, and the Reintegration Narrative

Aesthetics extend beyond interior spaces into public and therapeutic encounters, particularly through art and integration of nature.Prisons incorporating resident-led art programs, murals, and exhibition galleries transform institutional walls into sites of expression. In the Netherlands’ Scheveningen Detention Center, inmates collaborate with artists to create large-scale wall murals that reflect personal stories and cultural identity—bridging isolation and community.

“Art gives voice to people who’ve been silenced,” says art therapist Anke van der Horst. “It fosters connection and hope, essential precursors to rehabilitation.”

Natural integration—through controlled green spaces, rooftop gardens, and reflective water features—anchors aesthetic development in ecological and psychological well-being. Gardens not only offer therapeutic horticulture but visually soften prison perimeters, breaking the visual monotony of barbed wire and concrete.

Japan’s Kugayama Rehabilitation Center exemplifies this, where terraced gardens demarcate healing zones. “Nature invites patience and responsibility,” notes governance expert Taro Tanaka. “When inmates tend plants, they reclaim agency—key in re-entry preparation.”

Architects, Designers, and the New Vanguard of Prison Development The shift toward aesthetical development reflects a broader coalition of professionals—architects, psychologists, artists, and reform-minded prison planners—united by a shared vision.

Traditional prison architects have historically prioritized security over comfort, but today’s pioneers bridge these realms. Firms like勉 Architecture (formerly Elemental) in Chile and Foster + Partners in the UK now integrate sensory experiences into correctional masterplans with deliberate intensity. Their projects are not just buildings but therapeutic ecosystems shaped by human needs, not just operational checklists.

This interdisciplinary approach demands collaboration across unlikely silos.

Psychologists inform spatial choices to minimize stressors; artists contribute culturally resonant installations; botanists guide green space design; and engineers ensure safety without sacrificing warmth. “Prison development is no longer the sole purview of corrections administrators,” asserts Dr. Marquez.

“It requires a human-centered design philosophy—one where aesthetics are not ancillary, but foundational.”

Policy and Funding: Shifting Priorities in Institutional Design

While aesthesis marks a paradigm shift, its institutional adoption owes much to evolving policy and funding models.Governments and correction

Related Post

Wasmo Family Emerging as a Cultural Force: Sales, Influence, and Legacy in Modern Entertainment

From Birth to Immortality: The Extraordinary LifeCycleOfAWhale

Examining the Marital Status of Eminent Actor Martin Henderson