Inside the Human Arm: A Detailed Anatomy of the Upper Limb

Inside the Human Arm: A Detailed Anatomy of the Upper Limb

From the moment a newborn lifts a finger to grasp a caregiver’s thumb, to the precision of a surgeon’s steady hand, the arm is a marvel of biomechanical design and physiological complexity. The anatomy of the arm is not merely a framework of bones and muscles—it is a dynamic system orchestrated by nerves, vessels, and connective tissues working in concert. Understanding this intricate network reveals not just medical insight, but the evolutionary elegance embedded in human movement.

Every joint, muscle, and nerve plays a defined role, enabling gestures ranging from delicate pinching to powerful lifting.

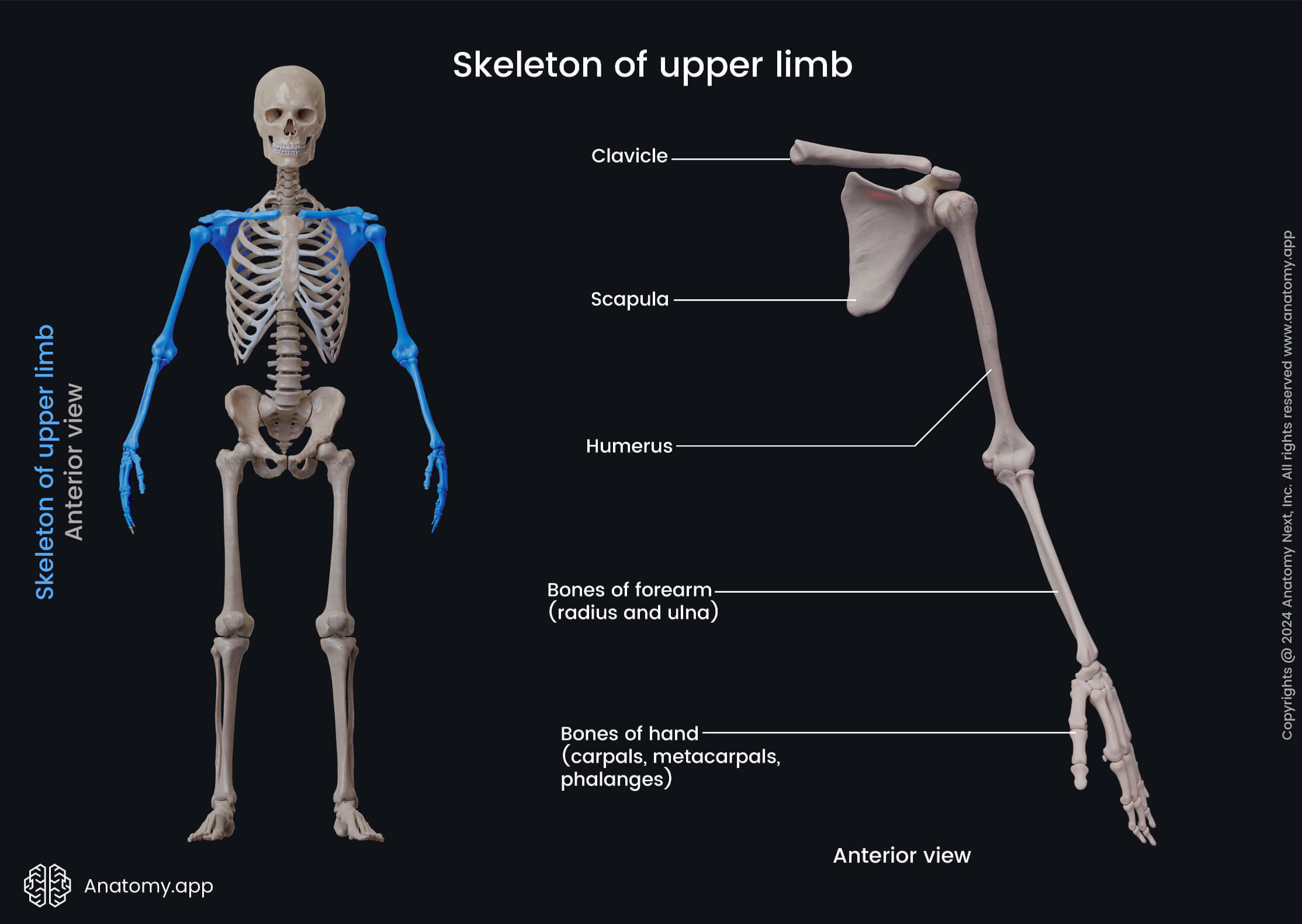

Anatomically, the arm is conventionally divided into three primary regions: the upper arm, the forearm, and the intricate interplay between muscles and tendons in the wrist and hand. These components collaborate seamlessly, supported by an extensive network of blood and nerve supply, ensuring both strength and dexterity. With over 30 muscles organized into three major functional groups, alongside key skeletal elements like the humerus, radial and ulnar bones, the arm’s design enables a near-unlimited range of motion.

The Upper Arm: Structure and Function of the Humerus and Surrounding Tissues

At the proximal end of the arm lies the humerus, the reservoir of bone that anchors both movement and protection.

This single long bone extends from the shoulder to the elbow, its proximal end shaped into two rounded heads—ball-and-socket joints that allow flexion, extension, abduction, and rotation. The medially located greater tubercle and lateral lesser tubercle serve as critical attachment points for rotator cuff muscles, essential for stabilizing the shoulder during complex motions.

The humeral shaft tapers distally, transitioning into two condyles—medial and lateral epicondyles—that anchor forearm muscles and support elbow mechanics. The humerus is encased in periosteum, a vascular membrane that nourishes the bone and facilitates healing.

Crucially, the radial and brachial arteries traverse the upper arm, supplying oxygenated blood while nerves—particularly the brachial plexus—route through, forming the body’s primary neural highway from the spine to the shoulder and forearm.

This segment derives much of its strength from the surrounding musculature: the deltoid initiates arm abduction, the pectoralis major pulls forward, and the triceps brachii extends the elbow. Yet, beneath this visible power lies a dense web of connective tissue—the fascia—that transmits force efficiently and maintains anatomical alignment during motion.

The Forearm: Mechanics of Flexibility and Leverage

Extending from the elbow to the wrist, the forearm is a sophisticated assembly of bone, muscle, and neurovascular structures designed for both fine control and powerful force. Comprising two bones—radius and ulna—the forearm provides rotational mobility unmatched in the human appendage, a key factor in turning the palm upward (supination) and downward (pronation).

The radius, closest to the thumb, allows the forearm to pivot around the ulna during twisting motions.

This dynamic interaction enables grip adjustment, tool manipulation, and nuanced hand positioning. The ulna, heavier and more robust, functions as a stable pivot, absorbing stress during weight-bearing or forceful movements.

Deep within the forearm muscle group, 16 distinct muscles organize into two major compartments: the anterior (flexors) and posterior (extensors), separated by a strong aponeurosis. The anterior compartment, rich in flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus, powers wrist flexion and finger bending.

In contrast, the posterior compartment—dominated by the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis, and extensor digitorum—controls extension and wrist action. These muscles, anchored by tendons that weave through carpal tunnels and through extremities like the flexor tendons with their associated pulleys, deliver precise movement with rapid response.

Tendons, often underappreciated, are processed collagen strands linking muscle to bone, capable of transmitting tremendous forces without buckling. The brachialis lies beneath the biceps brachii, a primary flexor especially powerful when the elbow is extended.

The flexor retinaculum binds these tendons into functional units, minimizing slack while permitting fluid motion.

The Wrist and Hand: The Pinnacle of Dexterity

The wrist is a complex joint complex composed of eight small carpal bones arranged in two rows, interlocking with the distal radius and ulna. This intricate configuration provides precision alignment and allows a near-360-degree range of motion—critical for tasks requiring spatial foresight, from typing to tile placement.

Supporting this mobility are 19 muscles originating from forearm tendons and embedding into the hand, plus one intrinsic muscle per hand—thenar (thumb) and hypothenar (pinky)—that fine-tune thumb and finger control. The wiring of these structures enables the hand’s legendary versatility.

The thenar eminence, a cluster of muscles beneath the thumb, facilitates opposition—a uniquely human trait allowing pincer grip and object manipulation unmatched in the animal kingdom.

The hand itself comprises metacarpal bones forming the palm, and phalanges—three per finger, two per thumb—culminating in a structure of ~27 movable joints. The metacarpophalangeal (MCP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints each contribute to versatile positioning and force distribution.

Ligaments stabilize these joints against tension, while tendons, including the flexor and extensor groups, transmit muscular force to bone, enabling grip strengths from a feather-light touch to a crushing grip.

Sensory innervation is equally sophisticated, with branches from the median, ulnar, and radial nerves delivering feedback critical for coordination. This fusion of structural stability and neurobiological precision defines the arm’s capacity for fine motor control, making it indispensable in both daily life and complex technical endeavors.

Vascular and Nervous Infrastructure: The Lifeline of the Arm

Supplying the arm’s complex tissues requires an intricate vascular network. The brachial artery, the high-pressure conduit from the heart, bifurcates near the shoulders into the radial and ulnar arteries.

Branching generously, they form the superficial and deep palmar arches, ensuring resilient perfusion to both muscles and digits. These pathways sustain aerobic metabolism critical for endurance and rapid response.

Nervated comprehensively, the arm’s nervous supply arises from the brachial plexus—a chaotic yet precise web of nerve roots originating at C5–T1. This structure branches into trunks, dividends

Related Post

Ismaili TV: Bridging Faith, Culture, and Global Storytelling in One Streaming Space

Subhashree Sahu Viral Video Unveiling The Truth Behind The Sensation: Behind the Hype, Fact, and Impact

Broadcom’s Bold H1b Sponsorship Signals New Era in Talent Development and Industry Collaboration

Mastering Flow: How the Metodo Gatti Trombone Transforms Trombone Technique