HowDoYouFindTheVertexFromAnEquation: Mastering Parabola Geometry with Precision

HowDoYouFindTheVertexFromAnEquation: Mastering Parabola Geometry with Precision

Uncovering the vertex of a parabola is more than a technical exercise—it’s the cornerstone of understanding quadratic functions across science, engineering, and economics. The vertex defines the curve’s peak or lowest point, directly influencing optimization, trajectory modeling, and even financial risk assessment. But how do practitioners reliably determine this critical point from the general equation of a parabola?

By applying a systematic approach rooted in algebraic form and geometric insight, anyone can unlock the vertex with confidence—no advanced calculators required. HowDoYouFindTheVertexFromAnEquation distills decades of mathematical rigor into a clear, repeatable method that transforms abstract symbols into meaningful geometric insight. Understanding the canonical equation of a parabola is the first critical step.

The most widely used form is the vertex form: \[ y = a(x - h)^2 + k \] where \((h, k)\) represents the vertex, confirming directly that \(h\) is the x-coordinate of the peak and \(k\) the corresponding y-value. But not every quadratic emerges in this neat form. Many are given in standard quadratic form: \[ y = ax^2 + bx + c \] At first glance, finding the vertex may seem opaque—but within this equation lies a proven shortcut that leverages symmetry and coefficients.

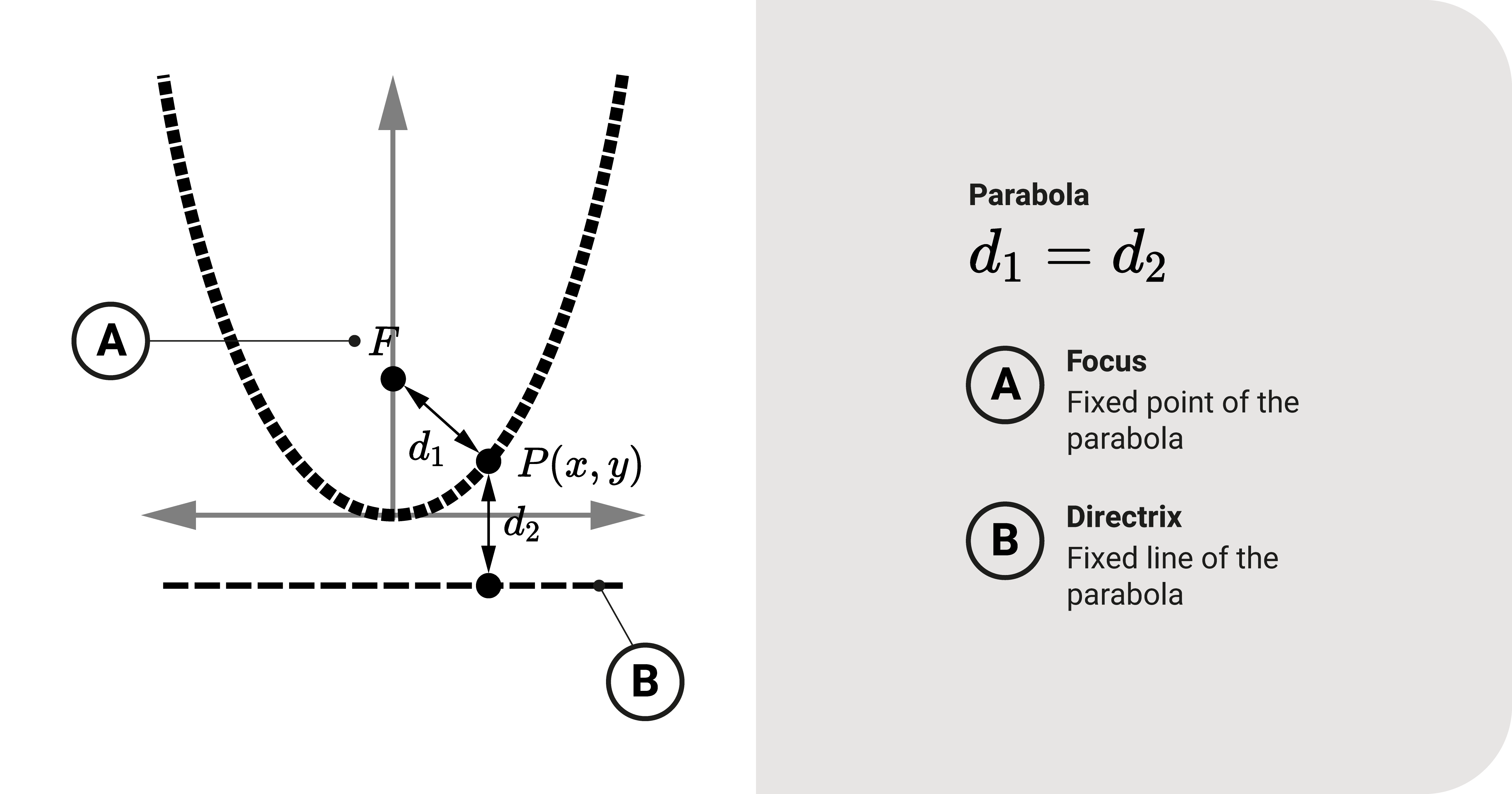

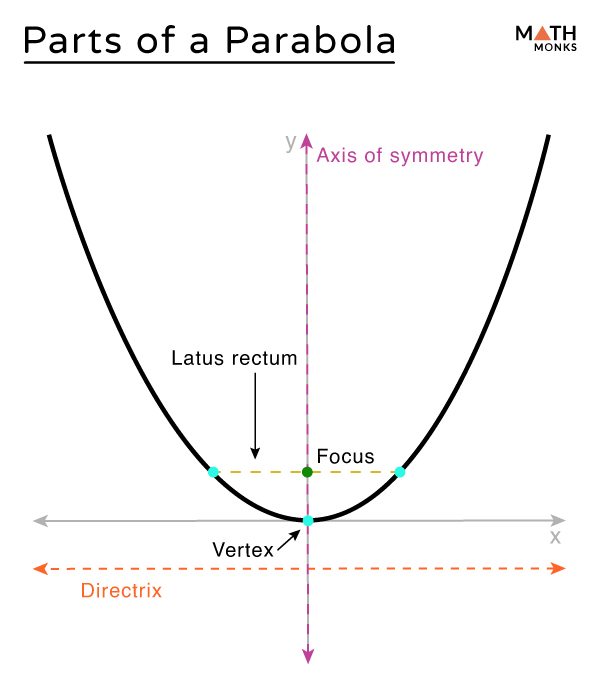

The key lies in isolating the axis of symmetry, a vertical line passing through the vertex. For any quadratic function, the axis of symmetry cuts horizontally through the parabola, guaranteeing that the vertex lies precisely on this line. This insight converts the problem into a single algebraic operation.

The x-coordinate of the vertex, \(h\), is derived from the formula: \[ h = -\frac{b}{2a} \] This coefficient-based derivation stems from factoring or completing the square—a foundational technique that reveals how the linear and quadratic terms interact to shape the curve. By combining the vertex’s x-position with substitution into the original equation, the full vertex coordinates \((h, k)\) are obtained, with \(k\) found by plugging \(h\) back into \(y = ax^2 + bx + c\).

Suppose a student encounters a quadratic equation written in standard form: \( y = 3x^2 - 12x + 11 \).

Applying the method requires three deliberate steps. First, identify \(a = 3\) and \(b = -12\), then compute \(h = -\frac{-12}{2 \cdot 3} = \frac{12}{6} = 2\). With \(x = 2\), calculate \(k = 3(2)^2 - 12(2) + 11 = 12 - 24 + 11 = -1\).

Thus, the vertex sits at \((2, -1)\)—a precise point that reveals both the curve’s minimum (since \(a = 3 > 0\)) and optimal behavior. This process proves efficient: beginning with coefficients alone, no graph is needed.

But what if the equation lacks obvious \(h\) and \(k\)?

In standard form, the \(-\frac{b}{2a}\) formula remains indispensable. For \(y = ax^2 + bx + c\), this rule applies universally, regardless of which variable is squared or whether \(a\) is positive or negative. The symmetry around the axis ensures that the vertex lies exactly halfway between any symmetric x-values—a geometric truth grounded in algebra.

Recognizing \(-\frac{b}{2a}\) not only speeds calculations but also strengthens conceptual understanding of parabolic behavior.

Beyond standard form, quadratic equations in various guises can still yield the vertex through transformation or algebraic manipulation. Consider vertex form recovered from standard form via completing the square—a powerful technique that exposes the vertex while emphasizing the transformation of functions.

Starting with \( y = ax^2 + bx + c \), completing the square yields: \[ y = a\left(x + \frac{b}{2a}\right)^2 + \left(c - \frac{b^2}{4a}\right) \] Now the equation is explicit: axis of symmetry at \( x = -\frac{b}{2a} \), vertex at \(\left(-\frac{b}{2a},\ c + \frac{b^2}{4a} - \frac{b^2}{4a}\right) = \left(-\frac{b}{2a},\ c - \frac{b^2}{4a}\right) \)—a simplified expression confirming prior logic. This method reinforces that vertex derivation is not magic, but an extension of algebraic strategy.

Practical applications underscore the importance of mastering this technique.

In physics, projectile trajectories follow parabolic paths; knowing the vertex allows predictions of peak height and timing. In economics, profit maximization relies on identifying the vertex of cost/revenue curves. Engineers use vertex data to optimize antenna placements or structural supports.

In each case, the ability to extract the vertex from an equation transforms raw numbers into actionable insight. HowDoYouFindTheVertexFromAnEquation is thus not just a formula drill—it’s a tool for real-world problem solving.

Ultimately, finding the vertex from an equation encapsulates the elegance of algebra.

It moves beyond rote substitution to embrace pattern recognition, symmetry, and transformation—cornerstones of mathematical reasoning. Whether in classrooms, labs, or workplaces, this method empowers learners and professionals alike to decode quadratic behavior with clarity and precision. As with any technical skill, mastery comes through practice, but once internalized, the process becomes intuitive, enabling rapid, confident solutions under any quadratic expression.

The vertex, once a geometric mystery, becomes a known landmark—one equation at a time.

Related Post

Bose QC Sc: The Audiophile’s Snack-Shop Sound in One Portable Machine

Mick Foley Claims He Is The Only WWE Superstar In History To Be Billed Shorter Than Actual Height

Unlock the Majesty of the Tetons: A Cartographic Journey Through Nature’s Masterpiece

Play Games On Site Playbattlesquare: Where High-Stakes Gaming Meets Strategic Battle Fire