How To Tell If a Substance Is Polar or Nonpolar: The Science Behind the Dip

How To Tell If a Substance Is Polar or Nonpolar: The Science Behind the Dip

Understanding whether a molecule is polar or nonpolar is fundamental to grasping chemical behavior, from how water dissolves salt to why oil floats on water. Polar and nonpolar substances exhibit distinct physical and chemical properties that influence everything from biological processes to industrial applications. Recognizing the difference isn’t just academic—it shapes how we handle cleaning products, interpret nutritional labels, and even design pharmaceuticals.

The key lies in analyzing molecular structure and electron distribution, using simple yet powerful tests grounded in chemistry’s foundational principles.

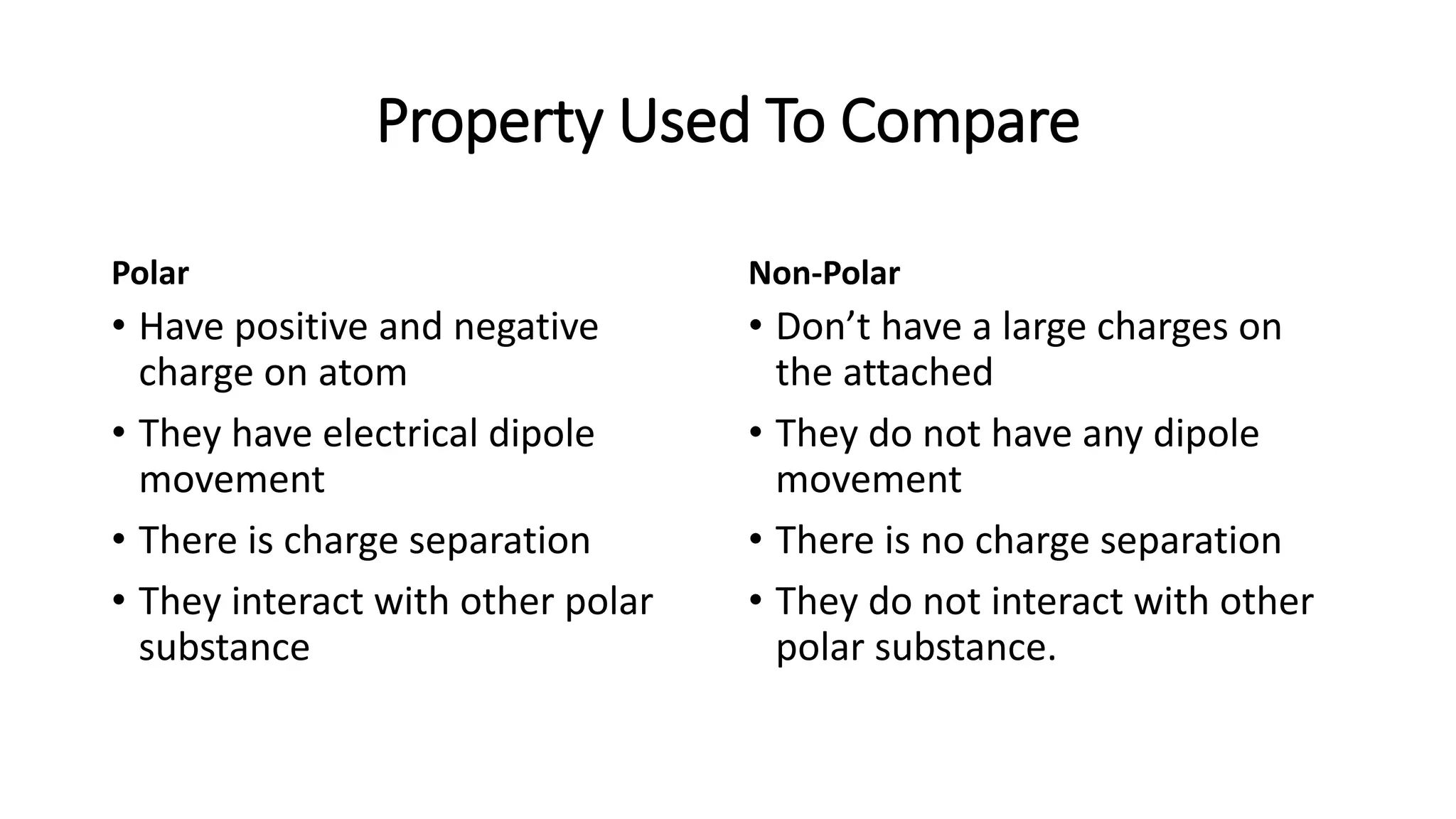

At the core of polarity is an imbalance in electron sharing. Polar molecules have an uneven distribution of electrons, resulting in regions with partial positive and negative charges, whereas nonpolar substances share electrons more evenly and lack such charge separation.

This difference explains key phenomena such as solubility and boiling points. For example, polar water forms strong hydrogen bonds, leading to high cohesion and a higher boiling point than nonpolar substances like methane at similar temperatures. Recognizing these behaviors starts with four essential criteria, each offering a window into the molecular dance of electrons.

1.

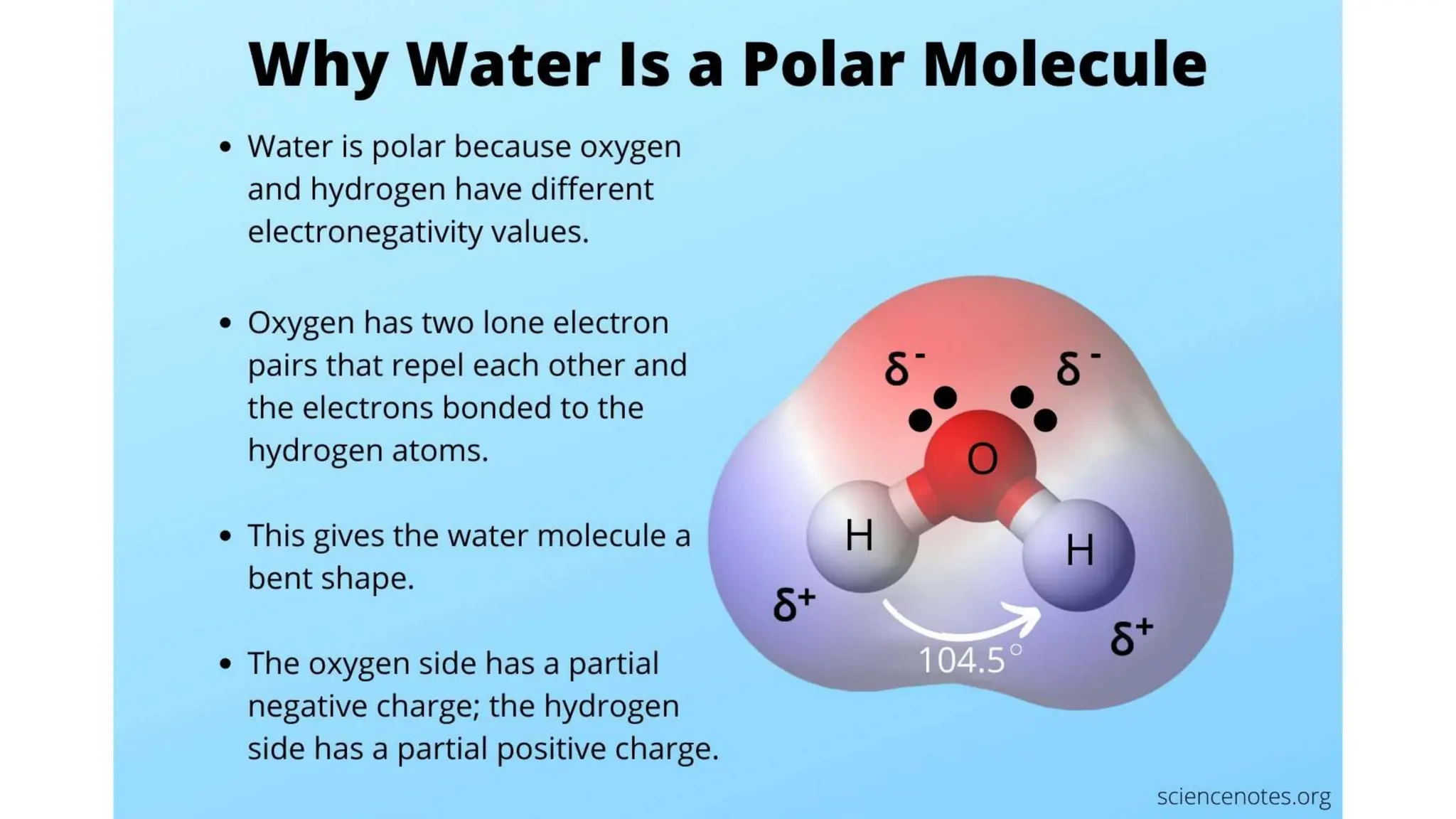

Electronegativity: The First Measure of Polarity Electronegativity—the ability of an atom to pull electrons toward itself—is the foundation for predicting polarity. When two atoms bond, if their electronegativity values differ significantly—generally a difference greater than 0.4—electrons are unevenly pulled, creating a dipole. Kill off qualitative judgment with quantitative focus: - Define electronegativity: A dimensionless scale where fluorine (3.98) is most electronegative and cesium (0.79) least.

- Apply the rule: A bond between atoms like oxygen and hydrogen (H₂O) is polar—oxygen (3.44) pulls electrons more strongly than hydrogen (2.20). - In contrast, a bond between two carbon atoms (C–C) with nearly identical electronegativities remains nonpolar, as electrons share evenly. “The electronegativity gap isn’t just a number—it predicts how electrons behave,” explains Dr.

Lena Cho, a physical chemist at MIT. “A large gap forces charge separation; a small one results in a uniform electron cloud.”

This principle extends beyond diatomic bonds. In polyatomic molecules, sum up individual bond polarities based on electronegativity differences.

For instance, in carbon dioxide (CO₂), each C=O bond has a polar dipole, but symmetry causes the molecule overall to be nonpolar—evident in its lack of attraction to water. In contrast, ammonia (NH₃) is polar despite N–H bond neutrality (electronegativity差 only 0.36) because geometry creates an overall molecular dipole.

2.

Molecular Geometry: Shape Trumps Individual Bonds A molecule’s geometry dramatically influences polarity, sometimes overriding bond-level electronegativity differences. Even with polar bonds, symmetry can cancel out dipole moments, yielding a nonpolar net. Consider the concept of vector addition: polar bonds point in different directions, and their dipoles may partially or fully cancel.

Take carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄), a classic intermediate example. Each C–Cl bond is polar—chlorine (3.16) is more electronegative than carbon (2.55)—but all four bonds are arranged tetrahedrally, pointing in symmetric directions. The vector sum of these dipoles cancels out exactly, making the molecule nonpolar overall.

“Molecular shape is the invisible architect of polarity,” notes Dr. Raj Patel, chemical educator and expert in molecular visualization. “You can have strong bonds, but shape decides if the giant charge imbalances annihilate each other.”

This concept also applies to water (H₂O), where two polar O–H bonds digitally align with a bent geometry, creating a strong dipole.

The resulting polarity enables water’s unique ability to dissolve ions—while ammonia’s bent symmetry delivers similar solvation power due to a balanced positive-negative charge distribution. The geometry-induced cancellation or amplification thus becomes a critical diagnostic tool.

3.

Building a Polar Nonpolar Checklist: Practical Testing Methods Transforming theory into practice requires structured troubleshooting using observable traits. Scientists and students alike benefit from a checklist that isolates two fundamental clues: electronegativity disparity and molecular geometry.

- Electronegativity Analysis: Compare all elemental atoms in the molecule using the Pauling scale.

Calculate average bond polarity by measuring electronegativity differences. A result above 0.4 typically indicates polarity, though context matters—sequential electronegativity shifts still matter.

- Symmetry Scan: Draw or visualize the molecule’s geometry. Identify whether dipole moments align constructively or destructively.

Symmetric shapes (tetrahedral, octahedral, linear with equal distribution) tend to cancel dipoles; asymmetric ones amplify polarity.

- Physical Property Correlations: Use solubility and dielectric constant as indirect clues. Polar substances dissolve in water but repel oils; nonpolar ones like grease resist aqueous solutions and exhibit lower dielectric stability.

Related Post

Biz Stone Twitter Biography Wikipedia Jelly Wife and Net Worth

Armed Services That Make Up SANDF Their Ranks and Salary Structure

PsP Games in 2025: Offline Brilliance and Free Downloads Rewrite the Retro Gaming Playbook

Noncompetitive vs Uncompetitive: Redefining Strategy in a Nonzero Game