How to Determine Electron Configuration: The Step-by-Step Guide to Decoding Atomic Structure

How to Determine Electron Configuration: The Step-by-Step Guide to Decoding Atomic Structure

Mastering how to determine electron configuration unlocks the key to understanding chemical behavior, periodic trends, and the fundamental nature of matter. Of all foundational chemistry concepts, electron configuration bridges the abstract idea of energy levels with the tangible properties of elements, from reactivity to bonding patterns. This article provides a precise, actionable methodology—used across scientific and educational settings—to accurately assign electron arrangements for any atomic number.

Electron configuration defines the distribution of electrons across an atom’s atomic orbitals, governed by quantum mechanics and implemented through key rules derived from basic principles.

Knowing how to determine electron configuration is not merely academic—it empowers chemists, materials scientists, and students to predict molecular interactions, ionization energies, and spectral signatures with remarkable accuracy. The process, while rooted in physics and chemistry theory, follows a logical sequence that demystifies what appears at first to be a complex puzzle.

Core Principles Govern Electron Placement

To determine electron configuration correctly, three foundational principles guide every assignment: 1. **The Aufbau Principle**: Electrons fill orbitals starting from the lowest energy level upward.2. **The Pauli Exclusion Principle**: No two electrons in an atom can have identical sets of quantum numbers, limiting each orbital to two electrons with opposite spins. 3.

**Hund’s Rule**: Electrons occupy degenerate orbitals singly before pairing, maximizing parallel spins to minimize electron repulsion. “The heart of electron configuration lies in these simple rules,” explains Dr. Elena Vasiliev, quantum chemistry researcher at MIT.

“Once these principles are internalized, even complex atoms become predictable.”

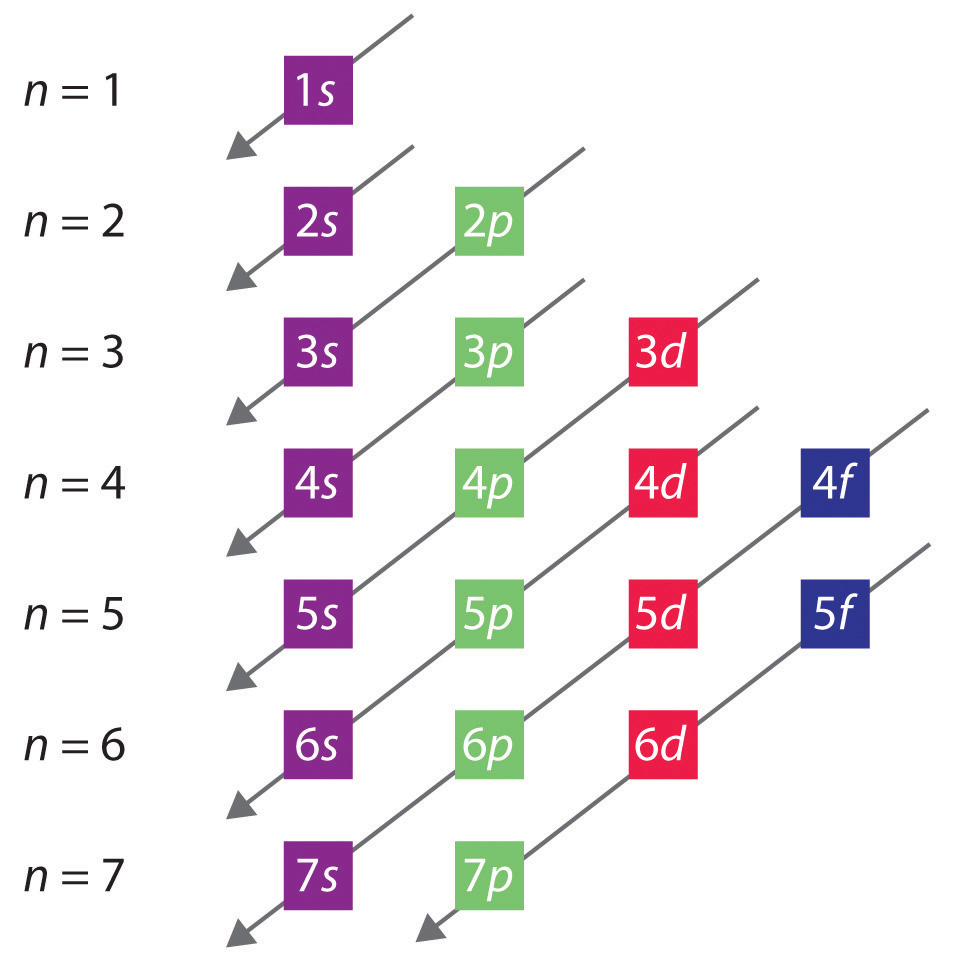

Mastering the Sequence: The Aufbau Diagram and Orbital Energy Order

The Aufbau principle provides the prioritization: energy levels and sublevels fill in a defined order—1s → 2s → 2p → 3s → 3p → 4s → 3d → 4p and so forth. While simple in theory, accurate application requires familiarity with the Aufbau diagram, which maps orbital energy levels based on quantum numbers. The conventional energy sequence sidesteps minor exceptions (like chromium or copper) by emphasizing that electron positioning is optimized for stability rather than strict n + ℓ values.For instance, chromium ([Arranged: 3d⁵ 4s¹]) prioritizes half-filled or fully filled stable d-subshells over a fully filled 4s layer. Historically, scientists mapped this order through experimental data—spectroscopic measurements and ionization energies—validating theoretical models. Today, software like quantum chemistry packages automate the process but understanding the manual method ensures deeper comprehension.

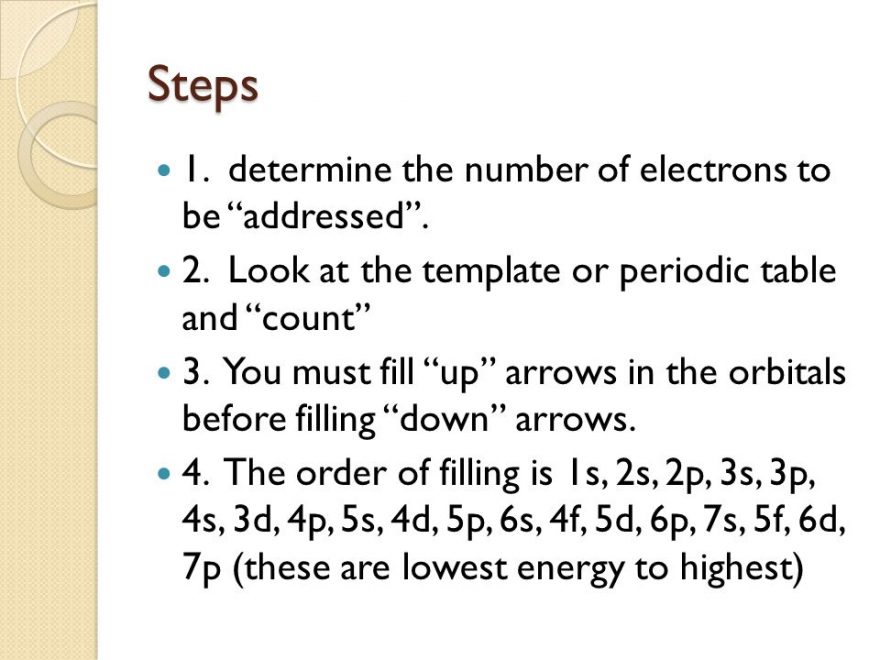

Applying the Rules: Step-by-Step Process

To determine electron configuration, follow this precise, iterative procedure:- Count Total Electrons: For neutral atoms, equal protons and electrons define the total. Ions alter this count by gain or loss—say, Fe²⁺ has 26 − 2 = 24 electrons.

- Batch by Subshells in Order: Begin with 1s, then 2s, 2p, followed by 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, and beyond, using the Aufbau diagram as a reference.

- Apply Quantization: Each s- and p-sublevel holds 2 electrons; each d- and f-sublevel holds 6. Useorial capacity densities to count capacity (s=2, p=6, d=10, f=14).

- Follow Hund’s Rule: Distribute unpaired electrons one per orbital before pairing—this reduces electron-electron repulsion.

- Adjust for Exceptions: Learn key deviations (e.g., Cr: [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹ instead of [Ar] 3d⁴ 4s²) based on enhanced stability.

Students and professionals alike rely on this framework consistently across chemical research and education.

Special Cases and Exceptions: Beyond the Standard Rules

While the Aufbau process is reliable, exceptions arise due to subtle energy differences and orbital stabilization. Two notable examples illustrate this: - **Chromium (Cr):** Instead of [Ar] 3d⁴ 4s², chromium adopts [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹.The half-filled 3d subshell offers superior exchange energy and symmetry, enhancing stability. - **Copper (Cu): normally would be [Ar] 3d⁹ 4s², but instead adopts [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s¹ for a fully filled d subshell, achieving maximum shell stability. Dr.

Vasiliev notes, “Exceptions prove the principle—not the process. The rules exist to optimize stability, not constrain creativity. Recognizing them strengthens conceptual understanding.”

Practical Tools: Calculators, Diagrams, and Modern Aids

Today, reliable electron configuration determination is supported by multiple resources: - **Quantum Calculators:** Web-based tools like the NIST Atomic Spectra Database or web applications provide instant, verified configurations.- **Orbital Diagrams:** Visualizing electron placement orbit-by-orbit demystifies energy order and helps verify manual calculations. - **Tabular Reference Guides:** The structured Aufbau chart remains indispensable for quick lookup during learning or testing. For students, practicing calculations manually builds fluency—critical for advanced work in spectroscopy, materials science, and quantum chemistry.

Automation aids speed and accuracy in high-throughput settings, but conceptual mastery remains essential.

Related Post

Revolutionizing Classrooms: How Classroom6x Transforms Learning Through Hyper-Personalization