How President Hoover’s Bold Ambitions Shaped America’s Great Depression Crisis

How President Hoover’s Bold Ambitions Shaped America’s Great Depression Crisis

Crossing the threshold of presidency in 1929, Herbert Hoover entered office amid skies unusually clear of economic storm—yet unknowingly stood at the edge of cataclysm. His tenure, marked by initial optimism and later by desperate crisis management, reveals a complex legacy defined by unyielding belief in voluntary cooperation, limited government intervention, and the fragile promise of American resilience. As the Depression deepened, Hoover’s policies and philosophy became both lightning rods for public frustration and defining moments in modern political history.

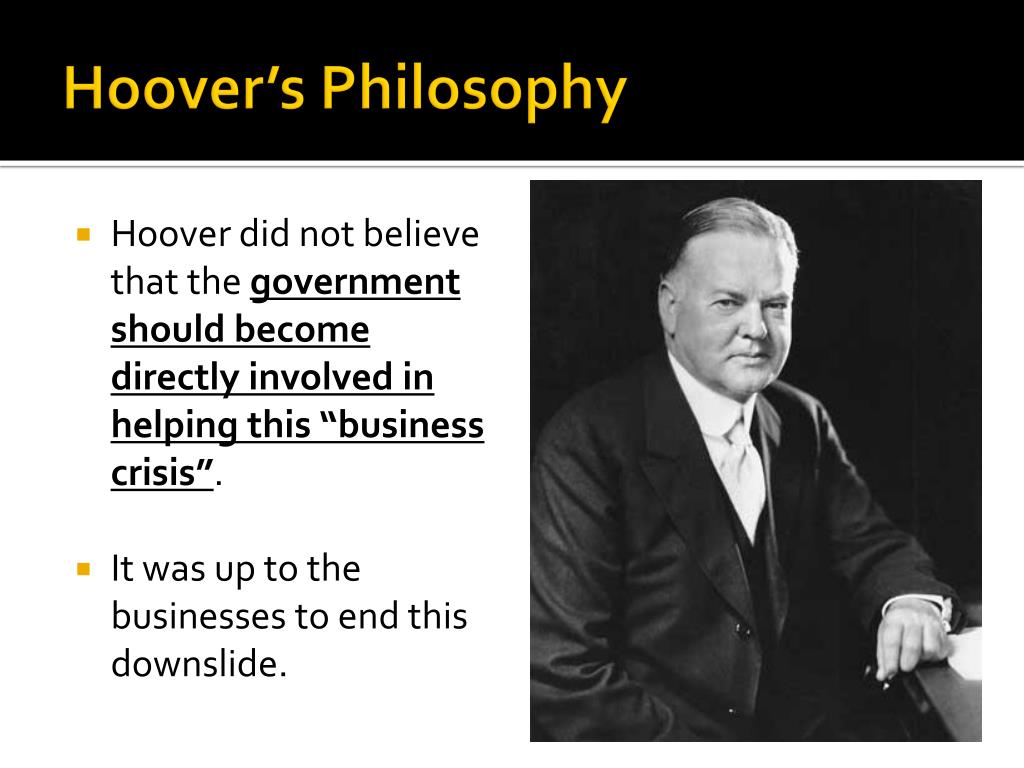

Hoover’s Pre-Depression Philosophy: A Faith in Self-Reliance and Limited Government Hoover’s approach to governance was rooted in a deeply held conviction that America’s strength lay in self-reliance, private enterprise, and decentralized solutions. A former engineer and wartime relief organizer, he viewed government as a facilitator, not a solver. In his 1919 speech on “American Individualism,” he declared: “The fundamental premise of American democracy is that men should be free to make their own way—free from excessive governmental control.” This ethos guided his early presidency, where he resisted direct federal relief, fearing dependency and undermining private initiative.

“Common decency compels our Nation to minister to the economic disaster afflicting our people,” he wrote in October 1929. Yet this philosophy proved ill-suited to the scale of collapse about to unfold.

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, Hoover responded not with sweeping federal intervention, but with a modest call for voluntary cooperation.

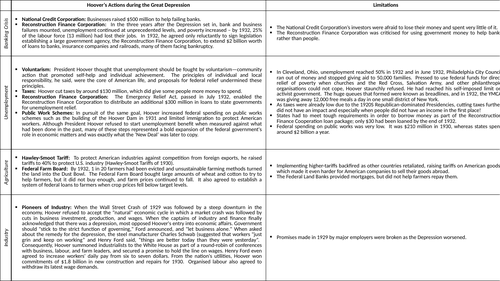

In his letter to industrial leaders in October 1929, he urged “comprising efforts” to maintain wages and continuous production, declaring: “The reason for the disturbance is not lack of demand, but a breakdown in adjustment among producers and consumers.” His administration established the Federal Relief Administration in 1930 to distribute limited aid—$25 million—through local charities, avoiding direct federal handouts that he saw as paternalistic or destabilizing. “We must not substitute the central authority for local initiative,” he insisted, advocating a restrained, morally grounded approach to crisis response. The Limits of Voluntary Action: Why Hoover’s Optimism Fell Short Despite Hoover’s earnest efforts, the Depression intensified with devastating force, exposing the fatal flaws in his hands-off strategy.

By 1931, over 4 million Americans were unemployed—peaking at 25% by 1933—while banks collapsed wholesale and industrial output plummeted by nearly half. “The spirits of the people are lowered every passing day,” Hoover acknowledged in a November 1931 fireside chat. His refusal to commit federal funds for direct relief, fearing inflation and dependency, drew sharp criticism.

Critics accused him of moral blindness to suffering; even some allies dropped out. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation, created in 1932 to lend money to banks and railroads, was seen too little, too late.

Hoover’s administration established numerous programs, but their reach was narrow.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) provided $150 million in indirect aid—primarily to state charities—yet couldn’t meet the demand. As one historian noted, “Hoover’s voluntarism was a gesture of dignity, but a distant one in an age of mass desperation.” Community relief efforts, though heroic, strained already fragile local economies and failed to close the chasm between private suffering and public capacity. Policy Shifts and Last-Efforts: From Reform to Reaction In 1932, facing election and rising unrest, Hoover introduced the Reconstruction Finance Corporation’s expanded role and pushed for the 1932 Bonus Army controversy—a misguided attempt to aid veteran pensions through direct federal spending, which backfired when the Bush Veterans Committee was violently dispersed by Army troops under General Douglas MacArthur.

This imperial show of force deepened public outrage and eroded what remained of Hoover’s reputation. In his final months, Hoover veered toward more interventionist measures—championing public works expansion and some direct federal assistance—though too little, too late. His May 1932 address to Congress warned: “We cannot appeal to selfishness, but only to the higher motives of patriotism and duty.” Yet public trust had eroded, and his pragmatic reforms were overshadowed by brutal perceptions of detachment.

Historians continue to debate Hoover’s efficacy. Some acknowledge his genuine belief in unity and temporary alleviation; others emphasize how his ideology and timing compounded national despair. “He sought to lead with conscience,” noted economic historian Milton Friedman, “but in a crisis demanding bold structural change, his restraint became rigidity.” Legacy: Hoover’s Enduring Impact on Crisis Governance Herbert Hoover’s presidency remains a pivotal case study in presidential leadership during catastrophe.

His failure to enact rapid, large-scale relief revealed the peril of ideological rigidity in moments demanding decisive action. Yet his commitment to American values—decentralization, personal responsibility, and restraint in governance—left a lasting imprint. The New Deal, emerging from his successor’s administration, built not on Hoover’s model, but in reaction to its limits.

Today, as policymakers face future economic reckonings, Hoover’s era stands as a sobering lesson: leadership in crisis requires more than intention—it demands action, empathy, and courage to adapt. His story endures not only as a chapter in history, but as a mirror held to the enduring tension between idealism and pragmatism in governance.

In the end, Hoover’s legacy is not simply of failures, but of a presidency tested beyond its design—where faith in the system collided with the raw reality of human suffering, reshaping expectations of what a president must do—and can do—when the nation stands on the brink.

Related Post

Michael Stevens Vsauce Bio Wiki Age Wife Iq Emoji Movie and Net Worth

Unlocking the Magic of Baseball Doodles: The Unsung Creative Power Behind Fan Expression

Richard Wolff’s Net Worth: A Reflection of Economic Thought and Academic Influence in Hidden Dollars

wavywebsurf Net Worth and Earnings