Hobos on the Road: Life on the Forgotten Pathways of America’s Roads and Railways

Hobos on the Road: Life on the Forgotten Pathways of America’s Roads and Railways

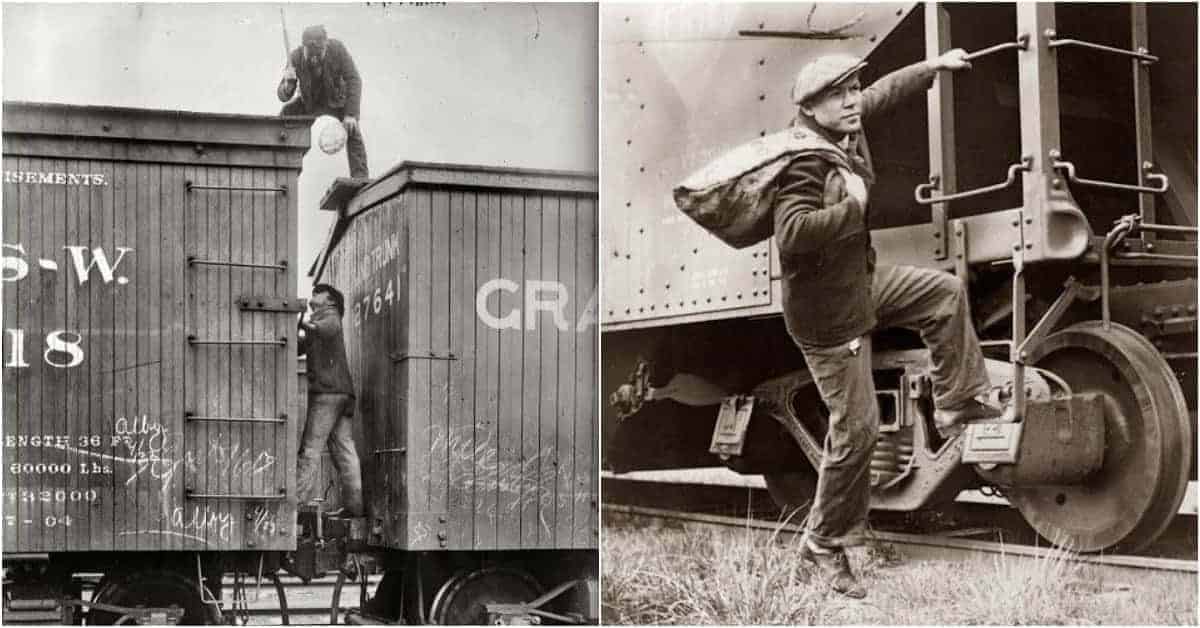

Beneath the weight of American highways and within the forgotten corridors of disused rail lines, a quiet, resilient subculture persists—those known as hobos, now more accurately identified as hobo settlers. Blending survivalism with travel tradition, modern hobos transform decaying roadsides and abandoned trains into temporary homes, forging an ephemeral life shaped by movement, resourcefulness, and a deep respect for the land itself. Far from mere squatter myth, hobo culture represents a complex adaptation to economic marginalization and the crumbling infrastructure of post-industrial America.

Hobos—derived from the shortening of “hobo” (originally meaning a long-distance migrant worker)—have evolved beyond their early 20th-century roots as transient laborers. Today, they are wanderers who embrace minimalism, knowing every scrap of food and clink of change carries survival importance. Many hobos travel on nostalgic rail corridors, utilizing slow-moving freight lines and rail trails that once fueled industrial growth.

“These old rails feed stories,” says former hobo and urban explorer Marcus "Mack" Reed, who spent over a decade documenting nomadic life on the Missouri Rail Trail. “You don’t just walk these routes—you listen to them.”

The Geography of Hobo Life: Railroads and Roads as Lifelines

Hobos rely on networks of disused or rarely used railways—what historians call "dead tracks"—as both shelter and passage. These corridors, often overlooked by modern transport planning, provide access to water, shade, and seasonal forage.In regions like the American Midwest and Pacific Northwest, hobos cluster near small towns where old depots and derelict sidings offer protection from inclement weather.

Survival depends on intimate knowledge of terrain and seasonal rhythms. “You learn to read the land like a map,” Reed recalls.

“Early mornings tell you where the morning dew still clings, where you’ll find moisture on rocks or grass—critical for drinking when a water spigot’s gone.” Hobos build makeshift shelters from scrap metal, tarps, and reclaimed wood, often sleeping at stops marked by rusted signals or century-old telegraph poles. These structures, though transient, reflect a precise understanding of durability and resource efficiency.

Navigating Legal and Social Shadows

While hobo culture emphasizes freedom, the reality is rife with legal ambiguity and social stigma.Many hobos exist in a gray zone—neither fully homeless nor citizens—since their mobility defies standardized housing and identity systems. Laws governing trespassing on private or abandoned right-of-ways vary widely by state, yet enforcement remains inconsistent. Local ordinances often target overnight camping, criminalizing survival tactics that have long sustained migratory communities.

“Migrant life isn’t about dignity—it’s about adaptability,” says sociologist Dr. Elena Torres, who studied hobo networks across six states. “These people don’t just survive; they map informal support systems: hidden springs, community-run shelters, shared food caches.” Despite marginalization, hobos develop informal codes—“the triangle rules” among hobo camps—promoting safety, resource sharing, and mutual respect.

“Tradition runs deep,” adds Reed. “We pass stories, songs, and survival tactics like heirlooms.”

Food, Fuel, and Funk: The Hobo Economy of the Margins

Foraging defines the hobo approach to nourishment. Seasonal berries, wild greens, river fish, and scavenged freight cars with preserved rations form the core of a portable diet.Equally vital is energy management—fuel scarcity means users hare fuel meticulously, humming tunes while conserving every drop. Many hobos collect wood scraps, bicycle tires, and broken machinery for kindling, reflecting a philosophy of minimal waste and maximum utility.

Scavenging extends beyond food.

Hobos repurpose old tools, bicycle parts, and electronics, creating repairs and contraptions from scraps. “A rusted bike wheel becomes a water bucket. A tire seal holds moisture under a metal lid,” Reed explains.

“Innovation isn’t luxury—it’s necessity.” This ingenuity underscores a broader ethos: hobos don’t wait for circumstances—they reshape them, channeling resilience into tangible, everyday survival.

Community and Identity: The Hidden Bonds of the Nomadic

Beneath rough exteriors and weathered boots lies a tight-knit culture rooted in trust and shared narratives. Camp gatherings function as both social and practical hubs, where stories of past routes are memorized and wisdom transmissions strengthen collective resilience.Younger hobos often drift after learning survival skills, but many eventually return—carried by invisible threads of memory, place, and belonging. “Every mile carved in the rail bed is a thread,” Mack Reed reflects. “We carry the road like a spirit.” In cities or solitude, hobos maintain quiet connections: handwritten notes left at abandoned shelters, coded signals over longlines, or songs sung late into twilight.

These practices preserve a collective identity irrelevant to conventional recognition but indispensable to survival.

Hobos Are Not Vanishing—they Adapt

hobo life persists not as a fading relic, but as a dynamic response to America’s shifting economic and material landscape. While critics often misunderstand their presence as transient chaos, hobos represent a living archive of mobility, ingenuity, and quiet endurance.As highways decompose and rail corridors reclaim their dormant power, hobos continue to walk, adapt, and endure—proving that in America’s backroads, resilience walks on necessity.

Related Post

What Is Net Worth of Bill Gates? The Riches of a Tech Pioneer and Philanthropist

<strong>Top Chinese English News Channels Define the New Era of Digital Media in an Increasingly Connective World</strong>

Unveiled: Hidalgo County Busted Newspaper Mugshots Reveal Photos That Shocked Texas

Delving_Into the Consequences of Vivaca A Fox: A Detailed Review