Herbert Hoover: From Mining Magnate to President, and the Tragedied Legacy of a Bygone Era

Herbert Hoover: From Mining Magnate to President, and the Tragedied Legacy of a Bygone Era

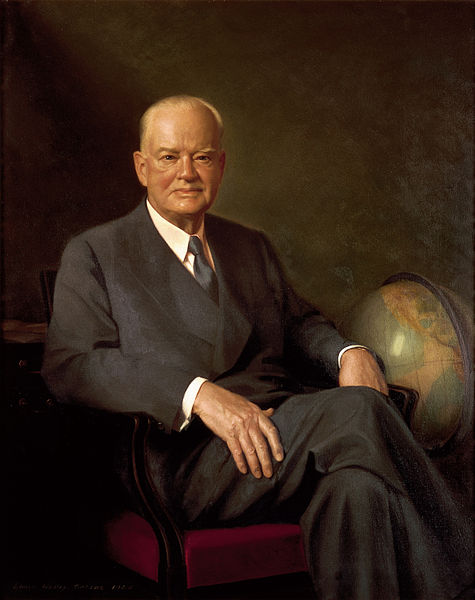

Amid the trembling economy and brewing global crisis of the early 1930s, Herbert Hoover’s dual identity as visionary industrialist and beleaguered president became synonymous with both ambition and failure. Once lauded for engineering American efficiency and global resource innovation, Hoover’s presidency was defined not by triumph but by the Great Depression’s crushing weight. His legacy, shaped by a lifetime of leadership in industry and government, remains a study in contrasts—brilliance under fire, resolve tested by catastrophe.

Born in 1874 in Iowa, Hoover’s early life forged a resilience that would define his career. A mining engineer by training, he rose to prominence through radical efficiency in resource extraction, overseeing massive mining operations across the U.S., Africa, and Australia. By 1914, he commanded one of the world’s most successful private enterprises, pioneering systematic management and global standardization.

His motto—"Efficiency is the muscle of civilization"—echoed through boardrooms and policy circles, yet would soon confront the limits of private-sector problem-solving in a national crisis.

Hoover’s path to the White House was unconventional for the era. A Republican with a technical mind, he served as Commerce Secretary under Warren G.

Harding and Calvin Coolidge, transforming the department into a hub of modern governance. He championed data-driven policy, promoted voluntary cooperation over government intervention, and pushed for infrastructure and education reforms long before they became mainstream. Yet when the stock market crashed in October 1929, Hoover’s faith in incremental policy proved inadequate.

Unlike his predecessors, he resisted large-scale federal spending, believing deficit intervention would erode fiscal virtue and individual responsibility.

Efficiency and Economic Policy: The Hoover Paradox

Central to Hoover’s worldview was belief in technical competence and voluntary cooperation—principles that guided both his business triumphs and political strategy. In industry, his systems approach reduced waste and accelerated growth, earning him reverence among industrialists.

Yet when faced with national depression, this same philosophy limited his response. Hoover argued that markets would self-correct and urged businesses to maintain wages and investment, even as unemployment soared past 25%. He refused immediate federal relief or relief-dependent programs, fearing dependency and constitutional overreach.

“This crisis is not a failure of policy, but of psychology,” Hoover stated in a November 1931 speech. “If Americans continue to act with patience, resolve, and mutual aid, recovery will follow.” But months later, breadlines stretched across cities, factories closed, and despair deepened—undermining public confidence in his measured approach. His administration did roll out limited measures: the Reconstruction Finance Corporation injected billions into banks and railroads, and the Emergency Relief and Construction Act authorized public works.

Still, public perception lagged—seen by many as out of touch with suffering masses.

key failures stemmed from structural and ideological constraints. Hoover’s opposition to direct federal aid accelerated the slide into poverty.

His insistence on balancing budgets under strain limited relief efforts, even as the nation hollowed out. “He sought to govern as a problem-solver by persuasion,” noted historian Allen Paramore, “but the scale of the collapse demanded boldness—something his restraint denied.” While Hoover expanded executive functions through technocratic innovation, he lacked the political firepower or rhetorical agility to rally a shattered public.

Beyond policy, Hoover’s international legacy reflected early 20th-century American ambition.

During World War I, his leadership in the Commission for Relief in Belgium earned global acclaim, supplying millions and solidifying a reputation as a humanitarian statesman. Yet in global diplomacy, he adhered to interwar idealism undercuts by economic collapse. He resisted aggressive intervention to stabilize Europe’s debt crises, favoring negotiated solutions—an approach that proved hollow as German resentment festered and Fascism rose.

Domestically, Hoover’s pro-business stance clashed with rising calls for structural reform, setting stage for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s sweeping New Deal.

Hoover’s post-presidency remained marked by quiet advocacy.

Though overshadowed, he continued drafting memoirs, critiquing policy shifts, and defending his belief in calibrated government action. In his later years, historians debated his legacy—some praised his intellect and integrity, others condemned divine-ordained failure. What Hoover Teaches Us The Hoover era remains a cautionary tale of institutional inertia and philosophical rigidity in crisis.

His strengths—in organization, global vision, and principled governance—struggled to translate into effective emergency leadership. Yet his story also underscores the limits of even the most capable administrator when confronted with unprecedented human suffering and structural economic collapse. As economic turbulence rises globally once more, Hoover’s legacy endures not as a failure of talent, but as a pivotal lesson in how leadership must adapt when times demand boldness, not just competence.

From visionary engineer to pragmatic policymaker, Herbert Hoover’s life mirrors America’s turbulent transition from unchecked optimism to enduring adjustment—a life both admired and redefined by history’s unflinching gaze.

Related Post

Herbert Hoover: The Unheralded Architect of Modern Governance and Humanitarian Response

Herbert Hoover: The 31st U.S. President Who Defined an Era of Crisis

Ann Cusack Movies Bio Wiki Age Husband Better Call Saul and Net Worth