From Hydrogen Bonds to Van der Waals: The Enduring Hierarchy of Intermolecular Forces

From Hydrogen Bonds to Van der Waals: The Enduring Hierarchy of Intermolecular Forces

In the invisible dance of molecules, the strength of intermolecular forces dictates everything from boiling points to solubility and even the structure of life itself. From the mighty hydrogen bonds that stabilize DNA strands to the fleeting London dispersion forces lingering between noble gas atoms, these forces fall on a clear spectrum—strongest to weakest—governed by molecular size, polarity, and electron behavior. Understanding this hierarchy is essential to unlocking the behavior of materials, chemical reactions, and biological systems across scales, revealing why water flows while helium escapes, why table salt dissolves while oil defies it, and how cells maintain shape despite chaotic environments.

London Dispersion Forces: The Humble Foundations of Molecular Attraction

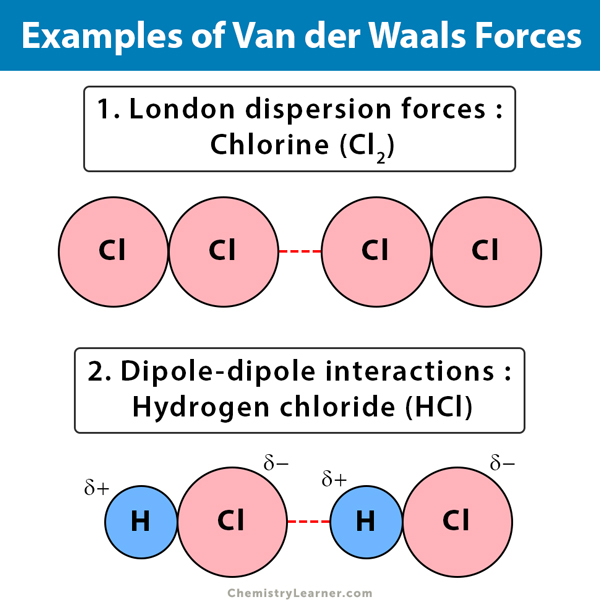

At the weakest end of the spectrum lie London dispersion forces—temporary dipoles arising from instantaneous electron fluctuations in atoms or nonpolar molecules.

Though individually negligible, these forces grow stronger with increasing molecular mass and surface area, enabling unexpected cohesion among seemingly inert substances. As physicist John Wingfield notes, “Even noble gases, unreactive and nonpolar, interact through these fleeting attractions—proof that electric wobbles matter.” These forces govern phenomena such as the liquefaction of hydrocarbons and the condensation of permanent gases at low temperatures. Their ubiquity explains why larger nonpolar molecules, like octane, boil at higher temperatures than methane, despite similar molecular weights, simply due to greater electron clouds and stronger temporary dipoles.

Key Characteristics of London Forces:

- Temporary, induced dipoles due to electron motion

- Present in all molecules, polar or nonpolar

- Strength increases with molecular size and surface area

- Dominant in nonpolar substances like alkanes and noble gases

- Rise with temperature, weakening as thermal motion disrupts alignment

Dipole-Dipole Interactions: Polar Molecules Engage in Purposeful Dance

As intermolecular forces strengthen, dipole-dipole interactions emerge in molecules with permanent charges—regions of partial positive and negative charge caused by electronegativity differences.

Unlike London forces, these align predictably, with positive ends attracting negative ends, leading to stronger, directional binding. “Dipole interactions are the next level of specificity,” explains chemist Maria Caldwell, “they allow polar molecules like ethanol to form reliable hydrogen bonds when hydrogen is bonded to oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine, dramatically altering their physical properties.” These forces elevate boiling points and enhance solubility in polar solvents, enabling compounds like sugar to dissolve in water rather than repel it.

Features of Dipole-Dipole Forces:

- Permanent dipoles due to unequal electron distribution

- Stronger than dispersion forces in polar substances

- Align spatially for efficient electrostatic interaction

- Significantly weaken with rising temperature

- Enable solubility in “like-dissolves-like” systems

Hydrogen Bonding: Nature’s Architectural Glue

At the strongest tier of intermolecular forces stand hydrogen bonds—special dipole-dipole interactions involving hydrogen directly bonded to highly electronegative atoms such as oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine. These bonds form strong, directional networks with remarkable cohesive power, enabling the stability of complex molecular architectures critical to biology and chemistry.

“A single hydrogen bond is not a stretch—it’s a strong partial interaction that resists disruption,” notes biophysicist David Wade. “In water, these bonds create an open lattice that lowers density, allowing ice to float—a phenomenon vital to aquatic life.’” Beyond biology, hydrogen bonding governs DNA base pairing and protein folding, making it indispensable to molecular recognition and structural integrity.

Defining Hydrogen Bonding:

- Occurs when H is single-bonded to O, N, or F

- Result of strong electrostatic pull between H+ and lone pairs

- Exceeds typical dipole forces by an order of magnitude

- Determines biology’s molecular blueprints and solvent behavior

- Pervasive in water, proteins, and nucleic acids

The Spectral Order: From Strongest to Weakest Forces in Nature

Ranking intermolecular forces from strongest to weakest follows a clear hierarchy: hydrogen bonding leads, followed by dipole-dipole interactions, then London dispersion forces. This sequence explains the physical behavior of materials across temperature and pressure extremes.

For example, in liquid nitrogen, strong hydrogen bonds are absent, yet dispersion forces are sufficient to maintain liquidity near absolute zero—proof that even weak forces can dominate under specific conditions. Yet, in everyday experience, this order surfaces daily: ethanol evaporates faster than propane, not because of stronger winds, but because hydrogen bonding in ethanol reduces intermolecular attraction slightly more than dispersion forces in propane dominate.

Ranking by Strength:

Why This Hierarchy Matters: From Materials Science to Climate Systems

Understanding the strong-to-weak gradient of intermolecular forces unlocks insights across disciplines. In materials science, engineers manipulate these forces to design polymers with tailored strength and flexibility.

In environmental science, the weakening trend of dispersion forces with temperature explains how scents—volatile organic compounds—evaporate more readily in warm air compared to cooler climates. In pharmaceuticals, hydrogen bonds dictate drug-target specificity, determining how well a molecule binds to a biological receptor. “It’s not just about strength—it’s about predictability and function,” says Dr.

Elena Torres, a physical chemist specializing in molecular interactions. “The same force type can drive radically different outcomes depending on context.”

Real-World Applications Highlighting Force Strength:

- Water’s survival hinges on hydrogen bonding, which stabilizes ecosystems and regulates climate

- Petroleum refineries rely on London forces to separate hydrocarbons during distillation

- Drug design exploits dipole interactions to enhance targeted delivery and efficacy

- Geopolymers use dispersion forces to bind materials without chemical curing, enabling sustainable construction

Conclusion: The Subtle Symphony of Invisible Forces

The hierarchy of intermolecular forces—from the immutable strength of hydrogen bonds to the fleeting whispers of London dispersion—governs the material world with silent precision. Each force, distinct in its origin and influence, combines to define phase transitions, solubility, biological function, and technological innovation.

More than just a scientific curiosity, this scale reveals why the ordinary world behaves the way it does—whether a drop of water freezes into a stable crystal, a fizzy drink retains its fizz, or a living cell maintains its 3D structure. As research advances, so too does our appreciation for these invisible molecular settlers, quietly shaping reality one interaction at a time.

Related Post